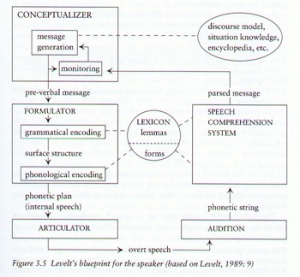

1. To facilitate and ‘speed up’ the development of speaking proficiency – as Levelt’s model of first language speaking production posits (see picture 1, below), spoken output requires the orchestration of many complex processes, some more complex than others, but all placing serious demands on our brain, in terms of processing efficiency. The speech production process starts in the conceptualizer that generates ideas and ‘sends’ them to the formulator which translates them into meaningful and grammatically correct sentences; then the monitoring system steps in checking the output accuracy before any sentence is uttered; finally, the articulator will orchestrate the use of the larynx, pharynx and mouth organs, whilst the monitoring system will have been overseeing speech production every step of the way.This process becomes even harder when the ideas generated by the brain (in the conceptualizer) need to be translated into speech in real time in a foreign language; the whole process slows down considerably – hence the hesitations and pauses in our language learners, even the more advanced ones, when speaking in the target language; and their errors, due more to cognitive overload than to carelessness (unless by ‘carelessness’ we mean lack of effective monitoring).

Picture1–Levelt’s model of language production (adapted from: http://homepage.ntlworld.com)

The complexity of the language production process and the challenges of performing it in a foreign language mean that our Working Memory has to juggle simultaneously all of the tasks that speaking involves and may lead less expert L2 speakers, as already mentioned, to slow down production and make mistakes due to processing efficiency. Hence, foreign language learners need to learn to master the lower order skills, i.e. effective control over larynx, pharynx and articulators as early as possible in order to ‘free up space’ in Working Memory for the kind of cognitive processing that happens in the conceptualizer and formulator; this will allow Working Memory to work more efficiently and focus only on the higher order skills, i.e.: the negotiation and creation of meaning, the transformation of meaning into the target language vocabulary, the application of grammar rules and self-monitoring.

Consequently, if we do not foster the automatization of pronunciation earlier on, through regular practice, we will delay our students’ development as fluent speakers. I have experienced this often in the past on taking on Year 7 classes which had been given very little pronunciation and/or speaking practice during two years of French/Spanish in Primary. Is this an argument against the Comprehensible Input hypothesis or The Silent way? Maybe.

2.Fossilization – On the other hand, if we plunge L2 learners into highly demanding oral tasks too soon, without focusing long and hard enough on pronunciation through easy and controlled tasks, their Working Memory will have less monitoring space for sound articulation, as they will focus on the generation of meaning (i.e. what happens in picture 1’s conceptualizer) with potentially ‘disastrous’ consequences for their pronunciation , in that they will resort to their first language phonological encoding to produce the target language sounds (language transfer). If pronunciation errors due to this issue will keep slipping into performance lesson after lesson, oral practice after oral practice, the mistakes will become fossilized and carried over to later stages of proficiency as fossilized errors tend to be impervious to correction.

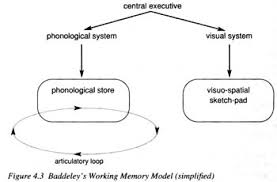

3.Phonological encoding affects recall – the more the learners become versed in the articulation of the target language sounds, the faster and more effective will be their retention of target language words in their Long-term memory (encoding). Why? This is because of the limitations of the ‘phonological encoding device’ in our brain’s Working Memory, i.e.: the articulatory loop (see picture 2 below). The articulatory loop has limited space (or channel capacity as psycholinguists call it), hence, if a word is not pronounced ‘fast enough’ the brain may not simply be able to encode it. The faster the articulatory loop ‘pronounces’ the target language the easier it will be (a) to memorize new words, especially longer and more challenging ones (from a phonological point of view) and (b) for Working Memory to process longer units of language (phrases/sentences) – as the less space words take on in the articulatory loop the greater the chances will be for longer words to be held in Working Memory at any one time. This speeds rehearsal in Working Memory and, consequently, uptake as well retrieval and production.

Picture 2 – adapted from: http://homepage.ntlworld.com/vivian.c/SLA/STM.htm

4. Stigmatizing output may lead to simpler L2-input from L2-native speakers – I am not a fan of Stephen Krashen but I do admit that he has come up with some great ideas, such as Narrow Listening and the one that relates to the point I am about to make; the fact, that is, that if a beginner/intermediate learner has bad pronunciation, any L2 expert who will interact with him/her may actually send easier L2 linguistic input his/her way presuming that his/her level of proficiency and/or language aptitude – as signaled by his/her pronunciation – is low. This will have negative implications for learning as if you are exposed to simplified input when you are at the early stages of language learning you may not learn much from it, not enough to bring you to next level, so to speak.

I tend to agree with Krashen on this one as I have seen this happen several times. And I will add, that often, in naturalistic environments, something even worse may occur: L2 native speakers may avoid engaging in conversations with L2 non-native speakers with poor pronunciation, for fear of not being understood or not understand and having going through the awkward process of asking the interlocutor to repeat.

5. The critical age hypothesis – This applies only to the first years of Primary school, when children are 5 to 8 years old (or younger); the age, that is, where the sensory-motor skills which control the movement of the larynx, pharynx and the articulators are still ‘plastic’, i.e. amenable to modification. After that age, it seems that the child’s receptiveness to pronunciation modelling/instruction diminishes drastically. If this is true, as compelling recent research evidence suggests, it is at this age that learners must be focused on pronunciation and taught ‘phonics’, pretty much as happens in their first language lessons, through fun and engaging speaking activities, lots of singing, listening and computer assisted phonetic learning.

Reblogged this on The Language Gym.

LikeLike

[…] Five compelling reasons to ‘over-emphasize’ pronunciation at Primary school (or at the e…. […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a great post emphasizing the importance of teaching phonological awareness at the primary level. How do you think we can teach it to EFL/ESL adult learners who lack ‘the plastic’ in their speech system.

Many thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for enjoying reading my post. Have you read by any chance my two posts on listening, the one on micro-listening enhancers and listening being a mistaught skill? That partly answer your query. Let me know if you need more on that. 🙂

LikeLike

It is a really informative post. Just one question, “Why does fossilization occur at an early stage of acquiring L2 pronunciation as compared to other skills?

LikeLiked by 1 person