Please note: this post was co-authored with Steve Smith of The Language Teacher Toolkit and Dylan Vinales of Garden International School

- Introduction: Why grammar instruction is often ineffective – a Skill-building perspective

Based on my professional eperience and on my readers’ accounts, much ML and EFL grammar instruction in the UK and, I suspect, across the world, is undermined by a number of shortcomings that stem from a misunderstanding of grammar acquisition and/or ‘sketchy’ curriculum design. In this post I discuss nine of the most serious shortcomings I have observed in 25 years of ML and EFL teaching. Please note that each of the points I make below is valid only if one espouses Skill-theory based theories of L2 language acquisition (also referred to in the literature as Skill-building or Cognitive Code approaches). If you operate within the C.I. / T.P.R.S. paradigm, you are very likely to disagree with every single one of the points I raise below.

- The starting-from-zero approach

More often than not, the teaching of a given grammar structure occurs ‘from scratch’, so to speak, with the students having had no previous exposure to it. However, learning – any kind of learning – is much more effective when the students can relate new input to past experiences. This is true of language learning too. That is why the ‘planting the seed’ technique or ‘anaphoric recycling’, facilitates and enhances grammar learning.

‘Planting the seed’ refers to planning the curriculum in such a way that, if you aim to teach, say, the present perfect in week 7 of term 2, the students will have come across several instances of its usage in aural and written texts throughout the preceding six weeks or even earlier – as ‘peripheral’ items. These previous encounters will have provided you and the students, in week 7, with plenty of past experiences of handling the target structure to draw upon and, in many instances, all you will have to do is help the learner connect the dots.

This technique works best when the students are – on each previous encounter – encouraged to notice the ‘seeds’ you are ‘planting’ and are provided with cognitive support when processing them. This does not mean that the ‘seed’ must become the main focus of the lesson – not at all. Nor does this mean that you are going to explain in detail how the structure works every time the students come across it; that would entirely defy the purpose of seed-planting. What I mean is that the unknown structure should not constitute a challenging obstacle to learner comprehension/execution of the task-at-hand. So, for instance, if you are ‘planting the seed’ of the present perfect, you may want to underline, write in bold or colour-code every instance of the present perfect in the written texts you give your students – to promote ‘noticing – whilst providing the translation in brackets or in a ‘help’ box.

You can do this with listening too, through jigsaw listening activities, for instance, in which the ‘planted’ structure is made to stand out through one of the above typographic devices so as for the students to pay more attention to it as they process the aural input.

- Minimal receptive practice and the ‘PPP-in-one-lesson obsession’

This refers to one of the greatest shortcomings of grammar instruction. Most grammar lessons unfold through a PPP (presentation, practice, production) sequence which goes way too quickly from the explanation of a grammar point to production. However, a very important stage, which plays a decisive role in grammar acquisition is nearly always missed out: receptive practice through the aural and written medium.

This hyper-neglected stage is very important, especially for the less confident of our learners, for the following reasons; (a) receptive processing is less cognitive challenging than production, especially when effective support/scaffolding is provided; (b) if the texts in use contain language the students are familiar with, they provide old material to hook the new items to, which may facilitate retention; (c) it models the application of the target structure in context, not in a communicative vacuum (as the sentences used by teachers and course-books as examples do); (d) reading allows more time for students to process the new information – production puts much more cognitive and emotional pressure on them; (e) aural modelling through listening – when the transcript of the track is visible to the learners- can be valuable in preventing many decoding/pronunciation errors which may impede acquisition – going back to the English present perfect scenario: think of the pronunciation of ‘I have read’ as opposed to ‘I read’; of ‘I have written’ versus ‘I write’. In French, I have significantly reduced the voicing of ‘-ent’ in the third person plural of the present indicative (e.g. ils parlent) by extensive modelling through listening practice.

Often teachers feel they have to get students to apply the target structure in production before the end of the same lesson in which they first introduce it. It is seen as evidence that ‘progression’ has occurred. However, the learning of any grammar structure – intended as its full automatization – requiring months of practice (see my article on grammar acquisition here), whether students ‘go productive’ or not by the end of the first lesson is not important. The more receptive practice the students actually get, the better. Having every single student leave the room feeling they have fully understood how the target structure works is better than having half of them go out having experienced problems using it in writing or speaking.

In conclusion, give the students lots of modelling of contextualized target-structure usage through receptive practice through lots of reading and listening activities, grammaticality judgment tests and metalinguistic tasks (e.g. Why is X used here and Y there? How many irregular forms can you spot here? Based on the text, how are adverbs used with the present perfect?). Let them experiment with the target structure in oral production in the next lesson.

- Building knowledge – not skill

If you were a football coach you would not teach someone how to dribble by simply explaining verbally to them how to do it, right? You would want them to try it out in front of you, give them some feedback on their performance and then get them to try again and practise extensively until you are sure they got it right.More importantly, you would not expect them to do it rightly the next time around – unless they are particularly gifted. You would know from your own experience, that it will take lots of practice before they will finally crack it – if they crack it at all. Finally, you would not assess whether they learnt what you taught them through a quiz at the end of a training session; you would want to see them play a match!

Yet this is what many teachers do when they teach their students grammar. They explain how a grammar rule works; give them a few examples and practise it through a few gap-fill exercises and maybe translations. Another classic is to get them to apply the target structure in some form of written production (e.g. to describe pictures or to write a creative or discursive essay). However, by and large, the typical way they assess uptake will be through a cloze test or a multiple choice quiz – Kahoot being the plenary of election in the UK, these days. A comparison with the football coaching scenario outlined above will clearly show how futile and ineffective this way of teaching grammar is; how little validity assessment carried out through quizzes and gap-fills is. Yet nearly everyone does it.

What this kind of teaching does is working on declarative knowledge of the language; on the understanding of the rules of the L2-system, but it does not bring about acquisition. Acquisition of a grammar rule can only occur through extensive practice across all four skills: Listening, Reading, Speaking and Writing. All four of them. And we may only say a grammar rule is acquired when it can be performed rapidly and correctly under Real Operating Conditions (i.e. in real life situations, whilst performing a real life task). Hence, grammar teaching needs to involve students in activities promoting fluency. But how do we achieve this?

Exactly like a football coach teaching his students how to dribble; first by modelling the use of the target structure to the learners through numerous contextualised examples (the receptive phase discussed above). Then by getting them to practise it in highly structured tasks (e.g. verb drills, gap-fills, easy written and oral translations, role plays). When the students are ready, the teacher will require them to carry out tasks which become less and less structured and pose greater cognitive challenge (e.g. oral picture tasks; solving a real-life problem based on a given scenario and prompts). The process will culminate in the performance of unstructured oral or written interaction under serious time constraints (e.g. an impromptu conversation with questions designed to elicit learner deployment of the target structure).

As one can imagine, this process involves lots of real-life oral and written communication aiming at building skill as opposed to creating knowledge – which sadly accounts for most of the grammar teaching I have witnessed in 25 hours of classroom observations.

Only extensive skill-building practice can bring about acquisition, not a few quizzes and gap-fills or corrections scribbled out in our students’ books or a list of targets. I was disappointed recently at seeing a great grammar lesson packed with oral communicative practice I observed end with a Kahoot; the answers to a multiple choice quiz will not tell us anything about the extent to which a grammar structure has been acquired.

- Compartmentalized learning

When the language curriculum is based on the course-book, grammar teaching is often ‘compartmentalized’, so to speak. The teaching of a specific structure is confined to a given unit or sub-unit of the course-book and then virtually forgotten. Although the students may encounter it here and there in future units, there is never evidence of systematic recycling of the target structure(s). Yet it is this systematic recycling that leads to acquisition.

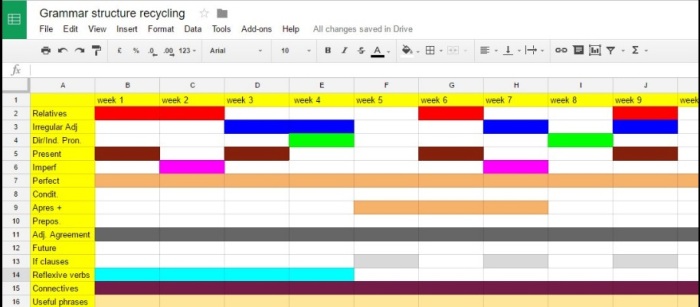

It is paramount when putting together the Curriculum/Schemes of work for a given year group/ proficiency level to identify the core grammar structures you want the students to have acquired by the end of the year and plan for opportunities to recycle them in every single unit of work at receptive and/or productive level. In my career I have never come across Schemes of Work which systematically do this – the greatest flaw of all!

Effective teaching is not simply about good classroom teaching and resources; what it is often forgotten is that curriculum design is nearly as important as the ability to deliver it. This is because of the nature of language acquisition. A well-planned curriculum being a curriculum which aims at ‘making things stick’, an effective curriculum designer never loses sight of any of the target structures; through systematic recycling s/he ensures that every memory trace ‘stays alive and kicking’ and becomes stronger and stronger as the course progresses.

This is relatively easy to accomplish and definitely pay dividends – all teachers need is regular reminders to go back to the structures previously taught every so often. Homework can play an enormous role in this respect by incorporating, say, in the week-8 assignment a section on a grammar structure covered in week 3.

- The often-unflipped flippable

Much – not all – grammar learning can be flipped, especially when it comes to less cognitive challenging grammar points and automatization work. Inductive tasks whereby the students are given a number of sentences modelling the use of the target structures (e.g. relative pronouns) and are asked to work out by themselves (by analyzing the sentences and through internet-based research) the rule governing their usage, can be given as assignments prior to the lesson.

Moreover, let us not forget that much of the grammar-learning work that leads to the acquisition of a target structure involves actively processing and/or using it. This can be flipped too. Think about the tiresome mechanical grammar drills that you may not want to do in class for fear of boring the daylight out of your students. Ask them to do this sort of stuff at home and – as I mentioned in the previous point – ensure that the assignments include new and old material.

- The tense obsession

In the modern-language-teaching world, less so in EFL instruction, tenses (and moods) dominate grammar teaching, as language-proficiency assessment has been tense driven for decades. Preposterous as this is, this tendency to identify grammar learning with tense-learning still persists even after the old English National Curriculum Levels have been scrapped. In schools where NC levels have not as yet been abolished, students are still being told that tenses are the key to progression along the acquisition continuum. This leads L2 instructors to overemphasize tense-learning at the detriment of other very important grammar structures which play a more important role in the execution of communicative functions.

By so doing, we convey to our students ‘bad’ metaphors of language learning, which they will live by in the years to come should they pursue language learning to higher levels. This is a very likely scenario when you hear students as young as 11 or 12 asking you obsessively “what tense do I need to get to level 5a? And 6b?”. But what about the ability of producing complex sentences, performing communicative functions effectively and accurately or the all-important ability to express oneself fluently under real operating conditions?

- Unrealistic expectations

As discussed above, coursebook-based curriculum design, when it comes to grammar instruction, is based on the unrealistic expectation that a given structure is acquired in six to eight weeks or even less. Nothing could be more preposterous. Acquisition meaning that students can perform the grammar structure accurately at (near) real-life speed, it will take way longer than that for students to routinize the application of a grammar rule. Allow more time in your Schemes of Work. The authors of the textbooks you use are not eminent second language acquisition researchers nor experienced curriculum designers – they do not necessarily know much more about teaching and learning than you do. The pace they set is more often than not, in my experience, flawed and unfair to the students; it does not take into account developmental constraints and never allows sufficient time for consolidation.

- Flawed assessment

The other day I was shown a grammar test that consisted of a series of gapped sentences to fill in with the present tense of verbs provided in brackets. A classic! I was all but surprised. This practice has been going on for a century or more and nearly everyone does it. Yet, how does that assess L2 students’ acquisition of the present tense? It assesses, at best, their ability to conjugate some regular and irregular verbs in the present tense, in a vacuum, totally divorced from communication. They do not even need to understand the all-important linguistic context surrounding the gaps.

My students conjugate verbs every day on the www.language-gym conjugator (for no more than 5-10 minutes!) often scoring 90 -100 %. Does that mean they have acquired present verb conjugations? Far from it. It is like saying that a five-year-old who has learnt how to kick the ball around his bedroom is fit to play a Premiere League match.

- Over-correcting but under-remediating

Based on my discussion above, it will be now pretty clear why spending a lot of time correcting surface level errors in our students’ written pieces is not an effective way to go about improving student grammar proficiency – unless you are prepared to invest a considerable amount of time in the remediation process, that is. Error correction is only the starting point, the awareness-raising ‘bit’ of the error-eradication process.

Let us go back to the football-coaching analogy. If you simply confine your intervention to providing the correction or coding errors and asking the students to self-correct you will be doing the equivalent of the coach telling his student that he should kick the ball differently and showing him how to do it – awareness-raising and modelling. Pretty much the equivalent of telling an alcoholic that drinking is bad, explaining why it is harmful and telling them not to drink again. But what about the all-important extensive practice needed for the student to re-learn how to kick? What about the rehab time and therapy needed by the alcoholic to stay away from drinking?

Unless teachers are prepared to spend hours and hours helping the students re-learn grammar structures, they’d better limit their marking to errors that are common to a fair number of students in the same class and ‘remediate’ them in lessons day-in day-out through regular recycling. A much more efficient and effective use of teacher time.

Here is a simple tool I use to ensure I recycle grammar over and over again across the areas of student structural competence I have identified over the years as the most problematic in French:

Concluding remarks

Grammar instruction still occurs, in many quarters, through outdated practices which defy neuroscience and, more importantly, common sense. From what we know about how the brain acquires cognitive skills, the way grammar is still taught and assessed in many school settings is highly ineffective. The most important message that I would like any teacher reader to take away from the above is that grammar teaching must be more skill -than knowledge-orientated and that without a carefully planned curriculum design (Schemes of work) which consciously aims at the routinization of the core target structures and strives to recycle them as much as possible throughout the course, across all four skills, effective L2 grammar acquisition cannot occur. Far too often grammar teaching and error correction stops at awareness-raising – the result being children that at best know how grammar rules work but cannot apply them correctly in spontaneous speech and under exam constraints for lack of R.O.C. practice.

To find out more about my views on grammar instruction and acquisition do read the book ‘The Language Teacher Toolkit’ I co-authored with Steve Smith.

I couldn´t agree more with you! This is a brilliant article. I just wish more teachers left the textbook aside and practiced more inductive and contextualized methods of teaching rather than the traditional ways.

I have one question for you. You recommend students doing a bit of verb drilling through a program called the language gym. How do you control or assess if students have actually been practicing?

Thanks in advance

Maribel

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] via Nine major shortcomings of L2 grammar instruction and how to address them — The Language Gym […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi,

Interesting article, and it evidently being about grammar teaching, I’m curious as to whether you’d advocate focusing on a particular grammatical structure, leading to practical use of that structure (a task where the emphasis is on, say, conditionals) or if you’d favour practical activities that incorporate a range of varying structures together? (A task where the emphasis is on achieving a goal such as arranging a doctor’s appointment or a holiday, for instance?)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Both it depends on developmental stage of learner

LikeLike

Reblogged this on mlk english courses: ELT teaching Blog and commented:

A great article !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Michele!

LikeLike

While teaching students with learning disabilities I used the Spelling Mastery program because of the extended practice and review that were integrated into the format. By 5th grade me students were often spelling more successfully than students with no learning disabilities. I always credited the “sytematic recycling that leads to acquisition” that you referred to in item #2. Makes perfect sense that this approach would also support the learning of grammar skills.

LikeLike