Introduction – The wrong question

The question in the title is one of the most common ones I am asked by colleagues from all corners of the globe. And whenever I have googled that question in the past ten years I have always invariably found the same answer crop up in EFL and MFL forums, blogs and websites: 8 to 10 words per contact hour. I have always wondered where those numbers came from as there is no consensus amongst researchers as to what constitutes an ideal number of new words to teach per lesson. Unsurprisingly so. As I will argue below, it is impossible to answer the question with a precise figure unless we define clearly what we mean by ‘teaching’ and ‘learning’ new words and have a 360-degree awareness of the target learning contexts with their unique interaction of affective and cognitive factors as well as other important individual variables such as the methodology in use, available resources, logistics, timelines, socio-economic factors, etc.

I personally ‘teach’ 20 to 25 words minimum per lesson, but what the word ‘teach’ means to me may not be what other colleagues take it to mean.

The good news

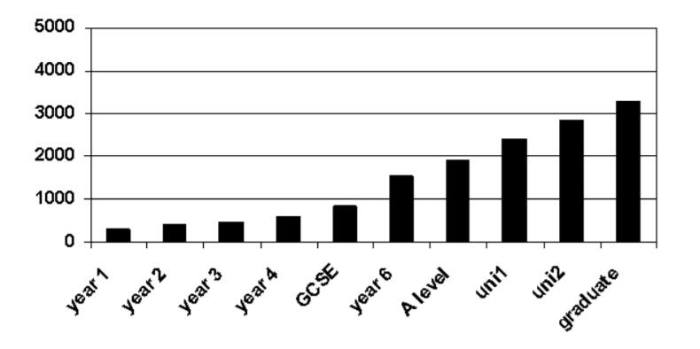

The good news for MFL teachers in England and Wales is that by the end of a typical GCSE course the estimated vocabulary size of a successful MFL student should be 2,000 words at GCSE Higher and 1,000 at GCSE Lower (Milton, 2006). If we divide that number by 5 years of learning French (from yr 7 to yr 11) two hours per week, that would equate with, 5.2 words per lesson, in truth a very manageable burden. In 2006, however, the national average showed that GCSE students in English state schools had accrued a vocabulary amounting to less than 1,000 words each (see picture, below, from Milton, 2006).

Why the title question is the wrong question to ask yourself

In deciding how many words to teach per lesson one has to take into account a number of contextual factors which play a decisive role in vocabulary acquisition and, more importantly, the depth and range of one’s learning intentions. The question ‘How many words should I teach?’ cannot be answered unless we first consider the following :

(1) Depth of knowledge – Knowing a word entails knowing many things about the word: its literal meaning, its various connotations, its spelling, its derivations, collocations (knowing the words that usually co-occur with the target word), frequency, pronunciation, the syntactic constructions it is used in, the morphological options it offers and a rich variety of semantic associates such as synonyms, antonyms, homonyms (Nagy and Scott, 2000). How deep one intends to go will entail spending more time hence teaching fewer words.E.g., if I teach a set of French irregular adjectives in terms of how they change from masculine to feminine, rather than just focusing on their main meaning and pronunciation of the masculine form, I will evidently have less time which will in turn limit the amount of words I can teach.

(2) Receptive vs Productive knowledge – as Nation (1990) notes vocabulary items in the learners’ receptive vocabulary might not be readily available for productive purposes, since vocabulary reception does not guarantee production. In other words, students may learn to recognize words whilst not being able to use them in speech or in writing. This difference is often overlooked whilst is crucial in planning a vocabulary lesson. If one is planning to simply teach new words for receptive use, they can teach, in my experience, as many as 40 with an able group, as recognition – especially through the written medium – is easier than production.

Moreover, although they are both receptive modalities, learning vocabulary through listening and reading obviously require providing students with two different types of extensive training which means that if you really aim to thoroughly develop the two skill sets – as you should – you will inevitably have less time available.

(3) Speed of recognition and production and degree of contextualisation – When we talk of recognition and production we need to consider (a) the element of speed and (b) the ability to understand the target words in unfamiliar contexts as markers of mastery . The faster a student recognizes a word (in familiar and unfamiliar contexts) as heard or read will tell us to what degree it has been automatized. The same applies to written and oral production (the hardest to automatize).

A vocabulary item can only be said to be fully acquired when it can be produced spontaneously (and correctly) within the context it was taught as well as unfamiliar contexts. With this in mind, to say ‘I taught ten words in yesterdays’ lesson’ is flawed. I may have presented those words and got the students to practise them and maybe they could recall them in isolation at the end of the lesson or even in one or more sentences. However, that does not mean the words have been learnt, because words are never used in isolation and not simply in two or three sentences learned by rote. Moreover, acquiring a vocabulary item takes weeks and in certain cases even months of practice in context.

(4) Word learnability – the learnability of the target word places further constraints on the number of words one decides to teach. ‘Learnability’ refers to the level of challenge a word poses to the learner. For instance: long polysyllabic words with unfamiliar phonemes will be harder for beginners to retain; abstract and connotative words are usually more difficult to acquire than concrete and denotative lexis; cognates are easier to recognize, etc. When deciding how many words to teach, the learnability factor is crucial.

(5) Shallow vs Deep processing – the method you use will also play an important role in deciding how many words you aim to teach. The deeper the degree of semantic processing the more likely the students are to recall them in the future. Deep processing includes activities such as: establishing association within new and old words, categorizing them; finding opposites and synonyms; writing the definition; inferencing their meanings from context; creating mnemonics to enhance future recall); odd one out; etc. Shallow processing involves little cognitive effort (e.g. learning by repeating aloud; the www.linguascope.com games). Teacher with effective vocabulary teaching methods are usually more successful at teaching larger amounts of words.

(6) Time, recycling opportunities and learning habits – the numbers of words you can teach will also depend on how many chances you can find in your lesson to recycle them. Do you have enough time, resources or activities in your repertoire for you to recycle each word you set out to teach a minimum of 5 to 8 times (through deep processing tasks) within the lesson? Do you have resources to ensure the recycling of the same items in subsequent lessons?

It takes me a lot of time and effort to create resources that allow me to effectively recycle all the target words I set out to teach in lesson 1, as well as all the subsequent lessons in which I revisit them. The more words you aim to teach, the more the effort you will have to put in follow-up lessons to create recycling opportunities. This is something you have to factor in when you decide on the number of words to teach in a given lesson or your teaching will have been in vain.

Connected with this is the issue of homework and learning habits and strategies. Are your students the kind of learners who do your homework consistently? If you flip vocabulary learning to them, will they actually do it? What the students do at home and how effectively their learning strategies are will have an impact to on how many words you plan to teach. In the case of one of the two year 9 groups I currently teach the amount of work they do outside the classroom – not their aptitude – profoundly affects the number of words I plan to teach each day.

(7) Chunks – The memorization of chunks is productive and powerful. It serves two objectives: it enables the student to have chunks of language available for immediate use and it also provides the student with information that can be broken down and analysed at later stages. Chunks allow you teach more words in one go as Working Memory can process chunks made up of 7+/- 2 items (Miller, 1956). Moreover, in real life we rarely process words in isolation.

The main advantage of the use of lexical chunks is that they build on the fluency of the language learner as they facilitate clear, relevant and concise language and are stored as ready-to–use units that can be retrieved and used without the need to compose on-line through word selection and grammatical sequencing. This means that there is less demand on cognitive processing capacity.

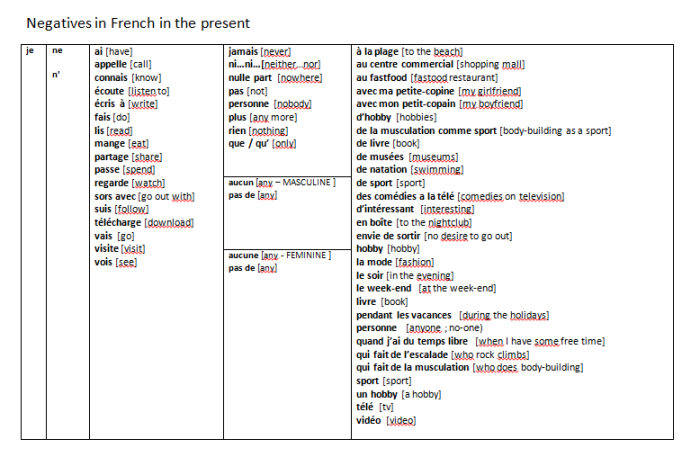

I hardly ever teach vocabulary in isolation, unless I am focusing on speed of recognition, decoding/pronunciation or spelling (e.g through the www.language-gym.com games). I always present vocabulary for the first time either through texts containing comprehensible input which allows easy inferencing from context or through sentence builders (see figure below). Teaching in chunks and short sentences allows me to recycle old material whilst presenting new material but also to include more vocabulary.

(8) Chunking and word awareness – Chunks have another important impact on how many words you will be able to teach. Once you have unpacked each chunk you taught, made the students notice the underlying grammatical pattern (e.g. I want you to go to the cinema) and got them to use that pattern over and over again with new lexical items, you will have enhanced the generative learning power of that chunk. The more morphological (e.g. prefix, suffixes) and syntactic patterns (rather than grammar rules) you teach your students the greater the chances for them to learn new words by ‘hooking’ them to those patterns. This process, known as ‘chunking’ happens in the brain at incredibly high speed in L1 acquisition and plays a crucial role in L2 vocabulary acquisition; hence, the more automatized the ability to recognize those patterns in aural and written input will be in your students, the more likely they will be to learn more words in your lessons.

Word awareness refers to a learner’s ability to ‘unpack’ the way words work both in relation to other words (synonyms, antonyms, collocations, etc.), their word class (adjectives, nouns, etc.) and how they are formed (prefixes, suffixes, etymology, similarities with mother tongue words, etc.). Word awareness promotes chunking, hence, acquisition. Creating a culture of word awareness in your classroom does not require much preparation, just asking lots of questions such as: Is it an adjective or a noun? Does this go before or after the verb? Does it remind you of a word in our language? Why does this word end in ‘-ly’?, etc. Research in word-awareness (also referred to as word-consciousness) it is still pretty scant, but many scholars believe that a strong emphasis on it in the classroom can greatly impact vocabulary acquisition. The more word -aware your students are the greater the amount of words you will be able to teach them in lessons.

(9) The students – last but not least. This is self-evident. Your students are the best source of evidence that you are gauging the amount of vocabulary input correctly. Regular low stakes assessment will tell you how much of what you have taught gets retained or lost along the way as the term advances. Online surveys through google forms or the likes will allow you to find out in a few minutes how they feel about their vocab learning, if you are being too ambitious or spot on. They can also help you find out about their learning habits.

Not all students have the same ability to learn vocabulary. Students who are low in any of the crucial components of language aptitude, especially Working Memory span and Phonemic sensitivity will be particularly disadvantaged and their presence in your class will have to be taken into account as they will be more prone to cognitive overload. Differentiated instruction will be a must in mixed ability classes.

The students’ current level of proficiency will also be an important variable to consider. The more advanced the learner is the easier for them will be to use conscious and subconscious learning strategies to acquire vocabulary. Hence you will be able to teach way more new words per lesson to your advance level students than to your GCSE ones.

Motivation is obviously another crucial factor. I am not going to discuss it as it is beyond the scope of this post. It will suffice to say that motivation enhances cognitive and affective arousal which in turns increases Working Memory span and the chances to memorize words. Hence, the more fun and relevant to your students’ lives and interests your vocabulary teaching is, the more words you will be able to teach effectively.

Concluding remarks

The issues above refer to but a few of the many factors one needs to consider in deciding how many words to teach per lesson. The most important thing I would like the reader to take home from this post is that vocabulary acquisition being a long process, planning a successful vocabulary lesson is about zooming out and thinking about the bigger picture and the longer term: what matters is not how many words you teach in a given lesson but how your subsequent teaching is going to ensure that those words will be automatized both receptively and productively by your learners across a wide range of contexts, both familiar and unfamiliar. In order to do so, the language instructor must master effective vocabulary teaching strategies, know the students well and implement skillful and systematic recycling never losing sight of the challenges that words and the contexts those words are taught in pose to the learner. A culture of word awareness that you build in day in day out through regular questioning, both metalinguistic and metacognitive in nature, will also facilitate your task and allow you to teach an increasingly larger amount of words per lesson, as your students become more alert to the morpho-syntactic properties of the target language words.Ultimately, it will be student feedback and regular low stake assessments that will tell you whether you are teaching the correct amount of words per lesson.

Totally agree, not sure exactly where this whole ‘8-10 words’ thing comes from. I wonder whether somewhere along the line, someone settled on ‘7 or 8 words’ based on a loose interpretation of ‘7 digits’ for short-term memory/memory span, then the number crept up! Who knows!

I think that distinction between receptive and productive is important. Also, learner motivation and need for particular terms is a factor. My board is often full of emergent language, and I think there’s no way students will remember that. We haven’t done much to practise it. But it’s normally come up because they really wanted the word or were trying to explain it. They often end up trying to use it in class without much prompting. I can’t say I’ve taught it, just introduced it…

As you’re the expert, I have a question about ‘chunking’. I always thought of Lamendella (neuro-functional theory) as being a starting point for discussion on chunking language, as a sort of forerunner to the lexical approach. Hadn’t heard of Miller… what articles would you suggest reading? And who talked about it before Miller? Thanks.

Cheers again, great read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was going to ask the same question, but I think the year in the reference is wrong, 1956 not 1965

Miller, G.A. (1956), The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on our Capacity for Processing Information. Psychological Review, 63, 81-97.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes it is 1956 my bad

LikeLike

Cheers! Sounds like a good read, I’ll check it out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello,

Good read that answers one of the questions that has plagued me for several years.

I agree that 5-8 new words, grammatical expressions, collocations, idioms or other kinds of chunks in an hour’s worth of teaching is the total we should be aiming for the objective of the lesson is output/production.

However, in some parts of the world, if we taught like this we would find ourselves out of work. This is because some cultures ascribe to ”the more we learn, the more will stick and the more we will be able to say or write” philosophy and are resistant to being told otherwise, even with references to back up what you are saying.

Another issue I have is that the culture I am teaching in means using books all the time,preferably by famous publishers. However, I have noticed that in one ”lesson” planned out by OUP, CUP and other such publishers (usually 2 pages in a coursebook, for example), the amount of input (or target new language to use in speaking/writing) usually exceeds this amount even in materials for children.

Because of the two aforementioned issues, I have resorted to having lists of new language that is around 10 for 7-12 year olds, and at around 15 for 13-16 year olds. Having them do homework and review/revise the new language list before the next lesson seems to help (seeing as they only see me once or twice or week, so there is time to do it), but I don’t think it is a fully effective substitute for material that provides less new language per lesson and therefore a slower rate (smaller amount) of input.

I would greatly appreciate any feedback on how to keep new language lists manageable in these teaching circumstances.

Thank you,

Louise

@AltitudeELT (now following you on twitter).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I found your article not only extremely articulate (which is not the case in many ESL resource web pages,) but also enlightening, therefore enjoyable, and thank you for putting in the time and knowledge. As a course designer for adult Spanish-speaking English-learners I use the web a lot for research. I will follow your contributions with interest and thank you again beforehand for your valuable insight.

LikeLike

Thank you Marco. Heart-warming words.

LikeLike

Thank you, I need the reference to this article, is it published in a book?

LikeLike

You are welcome. Not published in a book.

LikeLike