Of SAMR and SAMRitans – How the adoption of the SAMR model as a reference framework may be detrimental to foreign language learning

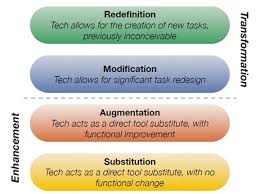

I was about to write an article about the SAMR model when I stumbled into a blogpost that encapsulated most of what I meant to say – http://ictevangelist.com/samr-is-not-a-ladder-purposeful-use-of-tech/. What the article points out is that far too often Puentedura’s model is used as a ladder, with Redefinition as the level of student engagement with technology we should aspire to in lessons. The most crucial point the author makes is that App Smashing every day in order to hit the Redefinition level can be a waste of valuable learning time. Another great point is that technology is only as good as the person who uses it; technology will not make you a more effective teacher.

In this article I will discuss, why, in the light of what we know about language acquisition and of my first-hand experience of the SAMRization of language learning on L2 proficiency, we should definitely not use the SAMR model as a framework to guide our teaching.

Issue n. 1: The kind of activities that the SAMR model implicitly advocates are detrimental to the development of speaking skills unless we are working at high levels of language proficiency

The kind of learning activities Professor Puentedura and other SAMR model supporters advocate put a lot of emphasis on the production of a digital artifact (a video, recording, game, etc.). None of such activities is conducive to the enhancement of oral fluency (not even speech recording), unless we are working with fluent L2 speakers who can conduct collaborative group-work in the target language. The same applies to aural skills, as listening skill practice can only receive a marginal focus in the kind of class-work envisaged by the model. Finally, lots of emphasis seems to be placed on writing, a skill that, in order to optimize the use of classroom time, should be preferably practised at home.

I have experienced first-hand how badly excessive focus on high-tech digital artifacts can damage learning whilst teaching students who had spent hours and hours, week in week out on iPad or computer work on ‘projects’ (e.g. making an iMovies about a theme) in the past: not much vocabulary learnt, poor pronunciation and oral fluency, over-reliance on google translator to generate language and, most importantly, low self-efficacy as learners. But, beautifully-looking and highly complex digital artefacts produced, indicators that ‘redefinition’ happened.

Issue n. 2: Divided attention

In terms of surrender value and learning gains, unless the students have automatized the use of the digital devices/media they are using and there are absolutely no technical glitches in the process, the learners, especially at the higher levels of the SAMR model hierarchy, ‘waste’ way too much time on handling the digital media (editing, choosing the right theme, background, photo, app smashing, uploading videos,ect.). I use the verb ‘waste’ because in a typical secondary school a class would get two hours – maybe three? – of teacher contact time per week. In such contexts every minute counts. Hence, unless course administrators double the time allocation for MFL teaching, the time lost in dealing with the technology, especially at Redefinition level, is not justified by the learning gains – which, in an MFL learning context MUST be measured in terms of language proficiency and not of enhanced ICT dexterity.

Moreover, from a Cognitive point of view, one shouldn’t discount the negative effects on learning of divided attention caused by the simultaneous focus of the learner’s Working Memory on the content s/he is generating and on the digital medium. I have often heard complaints from students that they spent so much time on the product looking as good as possible that the language became but a peripheral concern.

Issue n. 3: The non-ladder ladder

In the SAMR model, Redefinition happens when, in Puentedura’s words “Computer technology allows for new tasks that were previously inconceivable”. As already mentioned above, although some supporters of the SAMR model warn that the model is not a ladder, it does look like a hierarchy with a clear progression, in which Redefinition features as an aspirational goal. This may have negative implications for learning when the teacher – as I have seen on several occasions – does not focus on the progression that sound language teaching and learning requires, but aims for the top level of the SAMR model ladder in order to tap into the learners’ digital creativity. At lower levels of proficiency, this can equate to jumping to unstructured output production way too soon, when the learners are not developmentally ready and would benefit from more exposure to aural/written comprehensible input and more structured practice in the productive skills. In my experience, this is quite common in ‘techy’ MFL classrooms.

Issue n. 4 : Affective issues

The SAMR model states that at modification level “Common classroom tasks are being accomplished through the use of computer technology’. I know that the model is meant only as a heuristic and not as a pedagogic manifesto. However, it does seem to incite teachers to replace more traditional non-technological tools with digital devices. Whereas I have personally no problems with that, having myself created a whole language learning website (www.language-gym.com), I know that a fair amount of learners do have an issue with that. As a very good friend of mine has found out in the course of her Master’s degree research, a substantial number of students do not enjoy executing certain tasks using iPads or other digital devices all of the time.

As long as this model is used for what it should be, as a heuristic, a framework to gauge at what level of student engagement through technology a teacher is working, there is no harm done. But when course administrators or teachers misuse the SAMR model to advocate totally doing away with non-digital approaches to learning one has to worry, unless there is absolute evidence that every single stake-holder is on board.

Issue n. 5: No research evidence to support any claim that redefinition enhances language acquisition

The implementation of any new instructional approach should be based on credible research which demonstrates that it has a significantly higher potential to affect language acquisition than the methodology it is intended to replace. There is absolutely no solid and credible evidence that any integrated approach to foreign language learning corresponding to Puentedura’s Redefinition actually enhances language acquisition.

Issue n. 6: And how about things that cannot be replaced?

One ethical issue was already hinted at, above. What if students and/or parents do not want for technology to COMPLETELY replace traditional tools? Although I personally prefer writing on a computer or iPad, and I use iPads in every single lesson of mine, there are indeed several students I know who would prefer sticking to using a pen when taking notes or writing an essay and prefer worksheets to revise to digitally stored notes. How about personalized learning, then? If we advocate it, should we not have to heed this aspect of individual learner preference?

Issue n. 7: Metaphors we live by

Every single one of us lives by metaphors, behavioural templates that we assimilate from our caregivers, siblings, media and our entourage, including teachers. If we are developing lifelong learners, ICT skills must be learnt and dexterity and creativity with technology developed. However, lifelong learning skills in the realm of language learning relate more to human-to-human communication (whether by chatting face to face, on social medias, Skype or Watsapp), negotiation of meaning and the acquisition of life-long language learning strategies. The learning behavioural templates that constantly working at the Redefinition level models are dangerously conducive to overly technology-reliant life-long language learners. I accept that this may not necessarily seem a bad thing to some, as maybe that is what society is headed for: a totally digitally-assisted existence where we delegate the execution of an important part of our cognitive, motor and sensorial skills to electronic devices.

In conclusion, the SAMR model is for me of no great utility as a reference framework for teaching. It is just a taxonomy to describe the extent to which technology is integrated in lessons. It should categorically not be used to guide progression in any foreign language teaching classroom if our aim is to enhance our student’s balanced progression along the L2 proficiency continuum. In addition, it surely should not be used as a reference framework to impose a value judgement on MFL lessons unless there is credible evidence that redefinition enhances language learning. Thirdly, there is no credible research evidence that learning that occurs at the Redefinition level of the SAMR taxonomy actually enhances L2 acquisition. A model for the effective integration of MFL digital technology at the Redefinition level should be created and tested through rigorous research.

Finally, my belief is that technology can be a great learning enhancer if used by effective teachers who can inspire and motivate their students and understand the true nature of learning. It should not be a ‘crutch’ for lack of classroom presence and/or creativity and should serve not dominate what in my view should be the end-goal of our teaching: an all-round reflective and autonomous language learner who masters all four language skills effectively, is able to empathize with target language speakers and whose digital literacy allow him/her to function effectively in the work-place and society at large.

Introduction

Introduction

You must be logged in to post a comment.