Introduction

This guest post by Céline Courenq, Head of Languages at Patana International School in Bangkok, explores how one school moved away from “covering” content to achieving genuine sentence control through the Extensive Processing Instruction (EPI) framework. It is an essential read for any language teacher—and particularly those using EPI—because it provides a transparent, “at-scale” blueprint for moving from theory to classroom reality. Why it is so useful:

- Evidence of Impact: It documents how a shift from cognitive overload to the MARSEARS cycle transformed student confidence and fluency.

- Practical Implementation: Learn how to restructure units around communicative outcomes and “non-negotiables” rather than traditional topic lists.

- Resource Revolution: Discover how to turn Knowledge Organisers from passive lists into active retrieval tools for phonics and sentence building.

- Curriculum Resilience: It offers strategies for maintaining high standards and consistent progress even amidst high student turnover or staffing changes.

I want to thank Céline for this great contribution to the Language Gym blog and for being a staunch advocate of the EPI approach. Let me also congratulate her on having just obtained the EPI accreditation, graduating with a well-deserved DISTINCTION grade.

Implementing EPI at scale

Setting the scene

For several years, our KS3 curriculum looked ambitious. Students met a great deal of grammar early, we moved quickly through content, and assessments often included vocabulary and structures that students had not yet fully secured.

By the end of Year 9, however, something was clearly not right. Students had encountered a lot of language, but they could not reliably use it. Writing frequently relied on translation from English. Pronunciation was insecure, particularly in French, which then affected listening and speaking, as students struggled to connect written forms to sound. Some languages masked this slightly because pronunciation is more transparent, but the underlying issue was the same across languages: students lacked sentence control. In EPI, this reinforced the importance of listening and reading as primary modelling mechanisms rather than comprehension checks.

Students were encountering too much language too quickly for it to transfer into long-term memory. What we had perceived as progression was, in reality, cognitive overload. What we had labelled “challenge” was not producing the outcomes we wanted. The decisive shift occurred when teachers stopped asking “Have we covered this?” and started asking “Can they say this without thinking?”

This is where the EPI framework resonated strongly with us. It offered a different way of conceptualising curriculum design: sentence control was no longer a by-product of topic coverage, but the organising principle of what we did.

Making the Learning Architecture Explicit: MARSEARS in Practice

In practice, our curriculum aligns closely with the MARSEARS cycle, even when it is not foregrounded explicitly in lessons. Listening and reading are treated first and foremost as modelling tools, not as assessment checks. Students encounter carefully patterned input that repeatedly exposes them to the target structures in meaningful contexts before any expectation of independent production. This reduces guesswork, limits translation from English, and supports more secure pronunciation.

At unit level, this looks like:

• M (Modelling): sentence builders, phonics instruction and teacher modelling provide clear, controlled input

• A (Awareness): brief, focused attention to a key grammatical or phonological feature (minutes rather than a traditional ‘grammar lesson’)

• R/S (Receptive processing & Structured practice): input flood, processing tasks and systematic recycling across lessons

• E (Emergence): structured, then semi-structured output once patterns are secure

More explicit grammar teaching is used selectively later as consolidation rather than as a starting point. Making this sequence visible helped us ensure that progression was built on automatisation rather than assumption

What followed was not a change of resources, but a rethink.

We built a KS3 model designed to produce automatic sentence control under real constraints: tightly constrained non-negotiables, explicit phonics, cumulative retrieval, and assessment aligned to what has actually been taught and practised. The aim was to reduce overload, increase security, and make progress consistent across classes and cohorts.

1) What a Year 7 Unit Actually Looks Like

We now teach three KS3 units per year in each language. These units are not topic-driven in the traditional sense; instead, they are built around carefully constrained communicative outcomes.

A typical Year 7 Unit 1 focuses on students being able to:

• introduce themselves

• give personal information (name, age, birthday, where they live)

• talk about family, pets and basic relationships

• describe who they get on with and do not get on with

The aim is not vocabulary coverage. The objective is to achieve reliable mastery of a limited set of commonly used sentence structures.

From the outset, students work with:

• sentence builders (chunked language)

• explicit phonics instruction

• deliberately limited grammar (e.g. être, avoir, a small number of -er verbs, adjective agreement in French)

• high-frequency language recycled across the year

The unit is designed so that, by the end, students can produce accurate personal information without translating from English.

PHOTO 1 – Knowledge organiser extract showing learning intention and success criteria

Inpractice, a typical week might include:

• repeated listening and reading input modelling the unit structures

• short phonics focus linked directly to the core language

• guided sentence manipulation using the sentence builder

• frequent retrieval of previously secured non-negotiables

• brief, low-stakes checks to surface gaps early

• structured speaking or writing using only taught material

• teacher-led feedback focused on accuracy, control and pronunciation

The emphasis is on repetition, clarity and cumulative security rather than lesson-by-lesson novelty

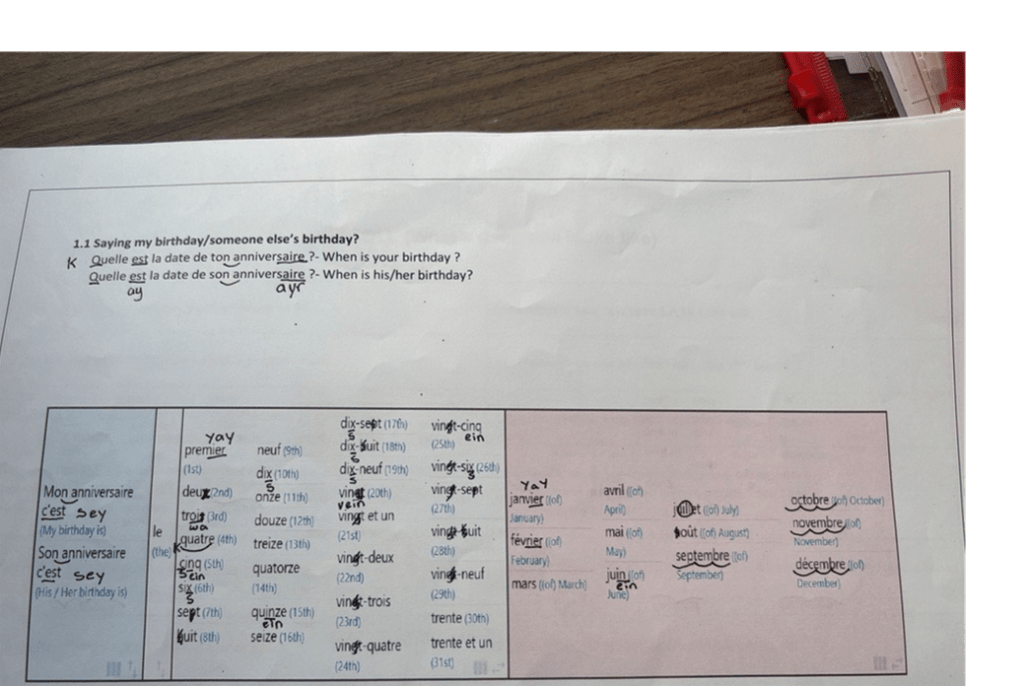

2) What the Knowledge Organiser Is For

Our knowledge organiser is not a vocabulary list. It is a retrieval and automatisation tool, designed to support both students and staff.

For students, it provides a single, manageable reference point for the unit. Each student receives a printed copy and uses it actively: highlighting phonics, underlining silent letters, marking liaisons, and tracking patterns. The organiser becomes a working document rather than a revision sheet.

For staff, it functions as a shared unit map. Everything sits in one place, supporting consistency across classes and reducing cognitive load for teachers and learners alike. Instead of multiple disconnected documents, the organiser anchors lesson planning, retrieval practice and assessment.

Each organiser contains, in one place:

• a phonics grid (sound–spelling correspondences)

• core verbs clearly laid out

• reminders about gender and agreement

• alphabet, numbers and key question forms

• sentence-builder language organised for manipulation

• a WAGOLL illustrating what success looks like

• clear success criteria

This ensures that what is taught is what is practised, and what is practised is what is assessed.

PHOTO 2 – Student-annotated sentence builder showing phonics and pattern marking

3) How Non-Negotiables Work in Practice

For each unit and year group, we define explicit non-negotiables: the small set of elements students must control before we move on.

In Year 7 French Unit 1 , these include:

• core forms of être and avoir across key pronouns

• a limited set of high-frequency verbs

• adjective agreement in controlled contexts

• a constrained lexicon with high reuse value

• key question forms

These appear consistently in sentence builders, the knowledge organiser, retrieval routines, speaking practice and assessment checklists.

4) How We Decide What Not to Teach

Equally important is what we deliberately avoid:

• early introduction of multiple tenses

• unnecessary full paradigms

• vocabulary added purely for perceived “challenge”

• moving on simply because something has been covered

Challenge is redefined as security and control, not content volume.

5) How Assessment Is Reverse-Engineered from Sentence Control

Assessment is built backwards from the intended communicative outcome.

Students are assessed only on language they have practised repeatedly. Strands for task completion, accuracy, range and complexity, pronunciation and fluency are separated so that performance is visible and meaningful.

Reading, listening and grammar tasks recycle the exact unit language. Assessment measures security, not exposure.

6) How Phonics Is Embedded Across Units

Phonics is treated as foundational. Students annotate phonics directly on their knowledge organiser and revisit patterns through reading, speaking and listening tasks. This had a significant impact, particularly in French, where insecure sound–spelling mapping had previously undermined confidence and accuracy.

7) How We Made This Work with Staff

We did not begin by dividing into language-specific teams. Instead, we worked in small mixed groups across languages and started by discussing skills: what did we want students to be able to do by the end of KS3, and what did they need in order to succeed at KS4?

Only after agreeing on these outcomes did we identify the grammar and vocabulary required to support them. This moved us away from topic coverage and towards sentence control.

This was supported through:

• sustained professional dialogue around EPI principles

• shared unit structures

• common markbooks

• internal reading and reflection

• targeted EPI workshops

We also benefited from external professional dialogue at key points. An early FOBISIA event delivered by Dr Gianfranco Conti helped shape our initial thinking. Several years later, he revisited the school, observed lessons and provided feedback on how our implementation had developed into a coherent KS3 system.

8) International Turnover: Making the Curriculum Resilient

The clarity of the unit structure and knowledge organiser makes the curriculum immediately visible for new students. Retrieval routines allow students to catch up through repetition rather than reinvention.

9) Tracking Security, Not Coverage

Regular retrieval and shared tracking focus attention on automaticity. Markbooks track non-negotiables over time so patterns are visible and intervention can be targeted early.

10) Obstacles and What We Learned

This change did not happen in ideal conditions. We worked within timetable constraints, textbook-driven habits, a culture equating challenge with more grammar, high student mobility, and the lingering effects of Covid on middle years.

There was also a period of trial and error as we sought the right balance between being overly prescriptive and insufficiently structured. Early attempts to impose tight pacing led to unintended pressure to rush content. We therefore made a conscious decision that:

• we assess only what has genuinely been taught

• we do not rush to “fit” a scheme of learning

• pacing adapts to the students in front of us

Assessment became a reflection of learning, not a deadline.

Validation from senior leadership was crucial in allowing us to prioritise security over surface complexity. Impact was gradual, as expected. Language learning is exposure-based and non-linear; automatisation only becomes visible after sustained retrieval and recycling.

Final Reflection

When KS3 is treated as structurally rigorous and cognitively realistic, KS4 outcomes improve naturally.

EPI gave us a framework for designing a curriculum in which every element works towards secure sentence control, and where confidence is built on something solid.

You must be logged in to post a comment.