Here is a list of evidence-based grammar-teaching tips based on my recent review of the specialised literature, which I routinely share in my Grammar workshops. I discuss many more in my workshops, of course, but I have been told that my posts are too long…

1. Don’t make the learning of grammar-rules the main focus of language instruction (Ellis and Shintani 2013). Make the grammar learning content lighter with students with low LAA (language-analytic ability , i.e the ability to treat language as an object of analysis and arrive at linguistic generalizations,which is at the core of the constructs of language learning aptitude and metalinguistic awareness, which are implicated in our ability to learn explicitly). These children are less good at analysing, spotting, memorizing and abstracting from patterns (faculties which correlate highly with IQ and rote-learning ability). As deKeyser, one of the strongest proponents of explicit grammar teaching has often pointed out, grammar instruction is more suitable for high-aptitude learners (de Keyser, 2015);

2. Make it enjoyable (Graham, 2022). Much grammar learning results in learner boredom (Murphy, 2022). Gamify it as much as possible through board games (e.g. No snakes no ladders), Interactive oral games (Oral ping-pong) and competitions (e.g. My Piranha grammar, Fast and Furious, Full circle).

3. Make it relevant to the children’s world and personal and academic goals, as relevance is key in fostering motivation to learn languages (Dornyey and Muir, 2019). In a series of French lessons on what one did last weekend, do we need every single verb requiring ETRE in the perfect tense, as textbooks usually do? How many times are the students ever going to be born , die, fall, go upstairs, downstairs, etc. in the context of such a unit?

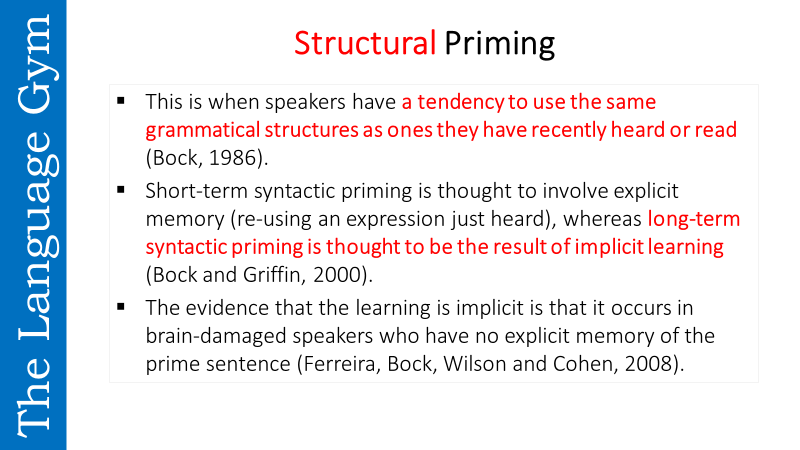

4. Use a synergy of Explicit and Implicit learning (Ellis and Shintani, 2013). To maximize implicit learning capitalize on the power of syntactic priming/persistence, i.e. a phenomenon whereby repeated processing of the same syntactic pattern leads to subconscious learning of grammar. This can be done using highly-patterned input, input-flooding and input enhancement, i.e. emphasizing specific grammar items, e.g. inflectional endings, through acoustic or visual devices (e.g. enunciating a verb ending louder; highlighting a preposition; colour coding case-endings in German). Another way to maximize subconscious learning is to exploit input at all level of grain (Nick Ellis, 2015), by staging intensive reading and listening (i.e. a series of activities which exploit the same texts at the level of phonological,lexical, grammatical, syntactic, semantic, discourse, etc. processing).

Figure 0: structural (syntactic) priming

5. Don’t spend too much time talking about grammar; grammar should be used more than it should be talked about.

6. For grammar to be used effectively and efficiently in fluent aural and oral processing it needs to be applied in a split second (Levelt, 1989). Hence, (1) be more tolerant of errors in spoken than in written production (Nation, 2013) and (2) ensure that you practise grammar through listening and speaking too; most language teachers don’t. (3) don’t overuse acronyms to learn grammar rules (e.g. MRS VANDERTRAMP) – if your learners become overreliant on them, they will never become fluent speakers

7. Introduce new structures in 100% familiar linguistic contexts (e.g. with known vocabulary) in order to decrease cognitive load (Conti and Smith, 2020). By the same token, avoid presenting and initially practising a new structure in high-element interactivity contexts as much as possible (Sweller, 2006).New grammar structures should be processed in sentences which are simple, short and where vocabulary and pronunciation will pose a negligible cognitive load.

8. Gradually phase out scaffolds. Move gradually from receptive processing to highly structured, then semi-structured and finally unplanned production. Don’t make the mistake as I did for many years, of explaining a grammar rule, then giving a list of examples and finally asking the students, without any substantive receptive processing, to produce sentences to show you they have understood. You will automatically exclude a significant chunk of the students and induce quite a few mistakes. Stage a few receptive tasks, first. Research suggests that successful acquisition of a grammar structure correlates highly with success (i.e. at least 60% accuracy) in the initial retrieval episodes (Boers, 2021). So ensure that you go to production when you are likely to secure a highly successful retrieval rate.

9. With non-transparent (deep orthography) languages where the sound-to-spelling correspondance is fairly low, such as French, do ensure that the students can accurately read aloud the morpheme(s) associated with the target structure. E.g., if teaching ‘ils regardent’, do ensure that they have routinised the correct pronunciation of ‘ent’ (i.e. that it is silent). Remember that even when we read silently, we still subvocalize what we read. A good strategy is to model and practise the grammar aurally first alongside their written form, as we do in EPI (e.g. through sentence builders).

10. Be aware of the factors which facilitate or impede grammar acquisition such as L1 positive/negative transfer, saliency or lack thereof, function-form mapping reliability, contextual factors, etc. (Nick Ellis, 2015). I have summarised these factors in figure 1 below.

Figure 1: factors facilitating the acquisition of an L2 grammar item

11. (Especially with students with low L1 literacy) Show (e.g., through a think-aloud protocol) how you would form and use the L1 equivalent of the target L2 structure first and draw or elicit a comparison from the students. Tribushinina et al, 2022 evidences that this contrastive approach is particularly effective with younger and weaker learners.

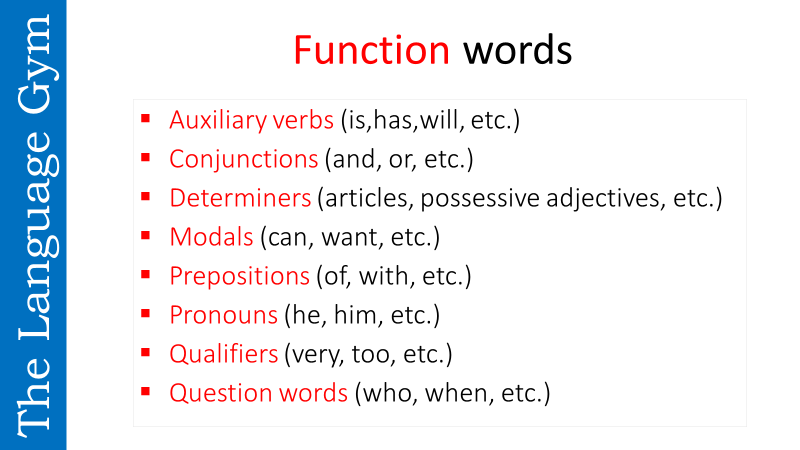

12. Be cognizant of the fact that when the brain focuses on meaning (e.g., in a reading comprehension) it doesn’t pay attention to form. Hence combine activities with a focus on form with others which have a focus on meaning (Ellis and Shintani, 2013) when exploiting texts. Note: the brain processes function words (e.g. determiners, auxiliaries, discourse an time markers, pronouns) as grammar, not as vocabulary. Hence, when we process a text for meaning quickly (as we do when we skim and scan a text to find the answer to reading comprehension tasks) we don’t usually process these key words which often our students don’t acquire until late in the acquisition process. This phenomenon is exacerbated by the fact that these words do not carry meaning crucial for comprehension (are not semantically salient) and we generally focus on content words when we read for meaning (the so-called Redundancy effect). Figure 2 provides a list of the key function words in a language.

Figure 2: list of function words

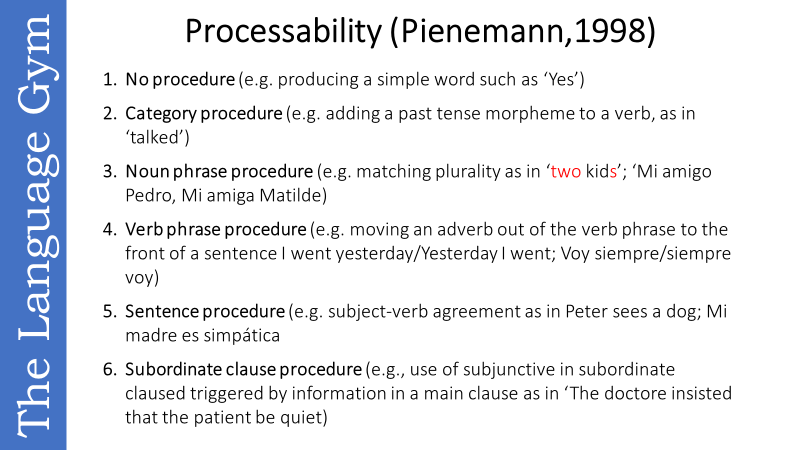

13.Mind processability theory, whereby one cannot learn a structure which requires for its execution the mastery of a number of cognitive operations, unless those operations have been proceduralised (Pienemann, 1998). For instance, according to this theory (which has been proven to be reliable by countless studies), no point teaching the perfect tense of French verbs requiring the auxiliary ETRE, unless the students have acquired 60% mastery of the sub-steps its deployment requires, e.g. selecting the correct present form of the verb ETRE, retrieving the correct past participle, making it agree in gender and number, etc. Sadly, most textbooks in England do exactly that, thereby setting up a lot of students, even those of high ability, for failure. Figure 3, below shows the procedures which determine the natural order of acquisition of a second language according to processability theory. Note that processability is a function of cognitive load, i.e.: if I have to form a sentence requiring five cognitive operations, my brain won’t simply be able to cope because of the overwhelming cognitive load. The beauty of teaching lexicogrammar is, of course, that chunk-learning bypasses the natural order and sequences of acquisition.

Figure 3: the six procedures determining the natural order of acquisition of grammar structures. It may take years to get to procedure 6 in real life acquisition, however, the students are often asked to produce subordinate sentences relatively early in the instructed acquisition process, thereby making lots of mistakes.

14. Be mindful of TAP (aka transfer appropriate processing): if a structure is learnt and practised in a specific linguistic context or through a given task, it won’t be easily transferred to another, especially once it has been routinised. A typical example: in many UK classrooms, reflexive verbs are usually practised exclusively within the context of daily routine, hence students find it notoriously difficult to transfer them to other contexts. Another implication of TAP: recycle your core (non-negotiable) items across as many contexts and tasks as possible (Conti and Smith, 2021)

15. Following on point 13 and 14, make your grammar teaching multi-modal, or grammar learning will be confined to only reading and writing – as it often unfortunately is the case in most classrooms. Grammar learnt only or mostly through reading and writing will be pretty much useless in the real world.

14. Still following on point 14 (about the TAP phenomenon), grammar testing should closely match practice (Purpura, 2005): if you practise a grammar structure through tasks X, Y and Z, it is not fair to test them using task W, unless you are testing for the learners’ ability to transfer knowledge. Yet, often students are tested on a given structure through essay writing when they may have practised it mostly through quizzes and multiple choice gap-fills.

15. Always assess grammar uptake (1) through a mixture of structured assessment (e.g. gap-fills) and free-production tasks e.g., talk to me about last weekend (Ellis and Shintani, 2013). The former will tell you if they can do it when there are prompts or a clear pattern as to what they are required to retrieve and usually pose a lower cognitive load; the latter is a test of spontaneous deployment of the target structure (hence it will tell you if the target structures have really been acquired).

16. Don’t simply assess the learning of a grammar structure based on a test carried out when the retrieval strength is high (i.e. right at the end of series of lessons on it, when it is expected and the students have had it in their focal awareness for weeks). Carry out impromptu assessment several weeks later too, to see how much has been truly retained (due to the law of memory decay, we usually forget around 80% of what we learn after 4 weeks in the absence of regular consolidation). Don’t make the impromptu assessment summative or formal, so that it won’t demoralize the students if they do badly. Some formative feedback will do.

17. Never assess using grammaticality (correctness) judgement tasks whereby a student needs to tell you if a sentence is grammatically accurate or not, as they have 50% chances of getting the answers right by merely guessing. Not a valid way to assess. NCELP does this and I still don’t get why.

18. Do not overload your curriculum – grammar coverage in UK textbooks is overambitious and inevitably results in shallow and short-lived learning. Decide on a limited amount of core structures which will be your non-negotiables, i.e. structures that, no matter how, every single learner can and must learn by the end of the course. By not overloading you enhance the chances of recycling. Which brings me to the next point.

19. Recycle, recycle, recycle. Grammar structures require more recycling than vocabulary because they require the learning and application of abstract knowledge in a short time window. Make sure that you find opportunities for recycling through retrieval practice activities, texts, my staircase design (Smith and Conti, 2021) but also, and more importantly, by sequencing your achievement units smartly so that each subsequent unit lends itself naturally to the recycling of the core structures practised in the previous one(s). Example of recycling/interleaving of ETRE and AVOIR in figure 4 below: . As mentioned in point 18, the fewer the core grammar items one teaches, the easier it is to recycle them. Having a narrow sets of core grammar items to focus on, doesn’t mean not having other peripheral items to teach explicitly and/or implicitly and/or incidentally.

Figure 4: Year 7 Unit 2 (partial) curriculum overview. The present indicative of AVOIR and ETRE and adjectival agreement are constantly recycled throughout a term of work on describing people.

20. Following on point 18: error correction only works when it addresses only a limited number of mistakes (Ellis et al, 2015). Hence, for the vast majority of your learners, only correct three or four error types max in your students’ input; these could refer to your non-negotiables, so that you have a powerful convergence of course objectives and corrective feedback. A powerful synergy.

I hope the above is useful to you and look forward to your comments. You will find this and more in our new edition of ‘The Language Teacher Toolkit” which will be published in a couple of months.

Gianfranco