1. Target vs Model Language : a hair-splitting distinction of much consequence for input design

In 1997, on my MA TEFL at the Reading University’s Centre for Applied Language Studies (CALS) I was introduced by one of my lecturers to Michael Lewis’ book ‘The Lexical Approach’, possibly the most innovative and inspirational piece of Applied Linguistics literature I have ever read in the field – a book that I recommend wholeheartedly to every language teachers.

Very early in the book Michael Lewis discusses a dichotomy that for ever changed my teaching: the distinction, that is, between Target Language and Model Language. This is how Michael Lewis (1993: articulates the distinction

Model Language is language included in the textbook or otherwise introduced into the classroom, as language worthy of study. It may consist of ‘real’ language, produced for purposes other than language teaching but introduced into the classroom as part of the learning materials […] Target Language is the objective of the teaching programme – language which, it is assumed, the student will ultimately be able to use. (where ‘use’ may mean actively produce or receptively understand)

This distinction inspired me, although my use of the two labels is different to Michael Lewis’. To me the term ‘Model Language’ is better suited to refer to the language the instructor intends to impart on their students, whilst ‘Target Language’ to describe the language one finds in ‘authentic’ texts and native-speakers’ utterances (i.e. the meaning modern language teachers traditionally attach to this term). This is the meaning I will associate with the two terms in the below.

A hair-splitting distinction you may think. And to a certain extent it is.

However, if you do believe that the input we provide our students with day in day out in our lessons has the purpose to model and sensitize the students to the core set of language phonological, collocational and syntactic patterns we purport to teach, then the dichotomy Target vs Model Language has huge implications for teaching and learning.

Even more so if you espouse the view – I discussed in my previous post – that effective teaching hinges on the successful modelling of language chunks and not merely of discrete words and grammar rules. Hence your Model Language will be patterned in a way which is instrumental to the constant recycling of those chunks and patterns and consequently even more artificial.

2.Input authenticity vs Input learnability

The main implication of the distinction for teaching and learning, in my view, is that for our teaching to be effective in sensitizing L2 learners to the target patterns we must not shy away from providing linguistic classroom input (Model Language) that sounds and reads significantly less authentic than ‘authentic’ L2 input (Target Language).

This goes counter to one of the most pivotal tenets of CLT (Communicative Language Teaching) pedagogy, the principle that learners should learn mainly or even exclusively from ‘authentic’ L2 input – a principle that is deeply embedded in the collective unconscious of many teachers thereby often affecting the way instructors and course books select and/or design instructional materials.

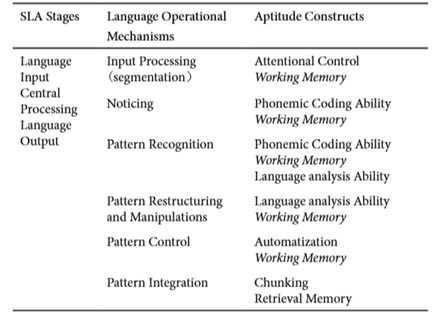

However, as I often reiterate in my blogposts, for input to be effective it must facilitate ‘noticing’ (i.e. the detection) of the target L2 features and recycle them in easily detectable patterns as much as possible. This requires input that fulfils the following criteria; it must

- be easily accessible in terms of meaning (as I repeat ad nauseam in my blogs, 95 % comprehensible without resorting to an extra-textual resource);

- be highly patterned – i.e. must contain several repetitions of the target sounds, lexis or syntactic patterns even though they might sound redundant and even less ‘natural’ (whilst still being acceptable) to the native ear;

- frequently recycle new vocabulary and patterns whilst recycling ‘old’ ones (as this strengthens retention and enhances comprehension);

- (in the case of aural input) be uttered at less-than-native speed.

‘Authentic’ and ‘Pseudo-authentic’ classroom language and texts rarely meet the above criteria, which makes them less effective for teaching and learning purposes, as they cause learners lots of divided attention by cognitive overload or distraction (e.g. from having to look to many words up in dictionaries) and, potentially, disaffection in less resilient learners.

This issue is far too often compounded by two major – extremely common – shortcomings of L2 instruction:

- Texts are usually underexploited by textbooks and teachers – one or two sets of comprehension questions and the class move on to the next task.

- Insufficient time is dedicated to receptive processing (reading and listening) of the target L2 items – an issue I often denounce in my posts

3.The primacy of the Model Language as conditional to learner developmental stage

As it is obvious, the ‘distance’ between the Model Language and the Target Language is bound to be greater at the early stages of L2 development, when students need more exposure to and drilling of the target patterns and chunks of language and when aural input must be uttered with more clarity and at slower speed. This parallels, in our first language development, the complexity ‘chasm’ between ‘Motherese’ and the input we receive as adults.

My colleagues (at Garden International School) and I, for instance, use with our beginners a core set of chunks we call ‘universals’ (high frequency chunks which cut across all topics) which we use as a starting point for the design and selection of the input and the instructional sequences to implement in our every lesson with them.

A sub-set of such ‘universals’, for instance, includes modal verbs followed by verb phrases which we recycle to death through our classroom language, the aural and written texts we give our students and the output we elicit from them through structured oral and written production tasks (pushed output).

In other words, we do not shy away from enhancing the surrender value of our input and the student’s pushed output at the expense of authenticity – as there is no way our ‘universals’ would ever occur in naturalistic input/output as often as they do in our own artificial Model Language.

At higher levels of proficiency, our list of ‘universals’ increases, which allows us a bit more freedom from the rigid structure that the narrower vocabulary and pattern repertoire of earlier stages imposes. This does allow for more frequent use of authentic texts.

Does this rule out the use of authentic material at lower levels of proficiency? Not entirely. I do believe there is a place for (simple or simplified) authentic texts, especially with more talented and motivated linguists, in order to provide practice and basic training in dealing with less predictable linguistic contexts autonomously through the application of inferencing skills and/or dictionary use as well as some cultural enrichment. In other words, authentic text use at this level of L2-competence would not necessarily serve the purpose of modelling the target patterns but more one of fostering autonomous learning skills (including cross-cultural understanding).

However, from novice to intermediate level it is my belief that the use of authentic texts or the pseudo-authentic texts found in the textbooks currently in use in many UK schools, unless heavily adapted, is more likely to hinder than facilitate learning especially when we are dealing with less gifted, motivated and resilient learners.

4. Conclusion: re-thinking the role and design of teacher input

Frequent exposure to patterned comprehensible input is not simply desirable, it is a pedagogic must. For the following reason:

Psycholinguistic research shows how language processing is intimately tuned to input frequency at all levels of grain: Input frequency affects the processing of phonology and phonotactics, reading, spelling, lexis, morphosyntax, formulaic language, language comprehension, grammatical sentence production and syntax (Ellis, 2002)

Sadly, more than often teachers are eager to see a product before the end of the lesson, the tangible evidence that learning has actually occurred.

As I often reiterate in my blogs, this is flawed from a cognitive point of view and may even seriously hamper learning. Why? Because the learning of an L2 item does not occur in one lesson, but over several months (or even years), going as it does through a painstaking non-linear process of constant revision and restructuring until control is finally achieved.

This over-concern for the product of learning results in many teachers often dwelling insufficiently on the all-important receptive-processing phase of learning any L2 item. After a couple of receptive tasks, they rush to some form of written or oral production.

If we do value the importance of extensive exposure to comprehensible patterned input in paving the way for more effective production in the short term and in securing more long-term retention, then we have to devote more lesson time to reading and listening and pay much more attention to the way we use classroom language and we craft aural and written texts.

The devil is in the detail, hence every opportunity must be seized by the instructor to recycle the target patterns and make them as noticeable as possible, especially when we are dealing with items that are less salient due to their morphology, position in the sentence, frequency of occurrence in naturalistic input or markedness.

This will often result in sacrificing authenticity for learnability, shifting, that is, from an emphasis on the Target Language (or a close approximation of it) to an over-emphasis on the Model Language. Once decided on the core set of patterns /chunks you want to impart and the vocabulary you are going to embed in them, your main concern will be to facilitate the uptake of those patterns in a way that maximizes the use of the little teaching contact time you have available.

At primary level, this shift is an absolute must, as the damage caused by insufficient receptive-processing work and recycling is most harmful at this stage of L2 development. At this age, when the brain is more plastic and sensitive to recurrent patterns, exposing L2 learners to highly patterned comprehensible input pays enormous dividends.

The consequences for curriculum design are obvious and not for the faint-hearted: in many cases an overhaul of your schemes of work and the creation of resources which include and elicit patterned comprehensible input. The former will be dictated by the need to recycle the core target patterns over and over again over the months and years to come. The latter by the need for expanding your repertoire of aural and written texts in order to enhance and deepen receptive processing. No easy endeavour, of course, one that many of my line-managers and colleagues over the years – with only a few enlightened exceptions – have time and again frowned upon.

Who looks at the Schemes of Work, anyway, apart from inspectors… right?

Could this be an opportunity to finally create Schemes of Work that are actually useful to you?

You must be logged in to post a comment.