The curve of skill-acquisition

You may have heard the expression ‘it’s been a learning curve’. Well, Cognitive psychologists working in the Skill Theory paradigm- which I am currently reading and writing about for my forthcoming book – have observed, for skills as different as making cigars out of tobacco leaves or writing computer programs, that learning follows a curve representing a power function that looks like the curve in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: the curve representing the power law of learning

The same is true of language learning. After intensive training (massed practice), L2 learners first experience a drastic improvement in task performance in terms of decreasing reaction time and error-making (represented by the steep decline); this decline indicates that the learners, after performing a task a few times have routinised it (what we call ‘proceduralization’).

For instance, a student may have learned to use the perfect tense of French regular verbs in the context of a structured communicative drill. Whilst at the beginning s/he was performing the task slowly, having to retrieve and apply the relevant grammar rule consciously (declarative knowledge), after several repetitions of the task s/he has now mastered the task.

When mastery has occurred and your students have routinized the task-at-hand (i.e. can perform it fairly effortlessly and speedily) and errors have decreased drastically, the curve starts to flatten (around point 20 on the curve) . This is where the typical grammar test, for instance, indicates the student has ‘got’ it and can apply the grammar rule fairly accurately and with some ease in the task they have been practising (although not necessarily in other tasks).

Automatization is a long process

At this point, if practice is continued, research shows that the curve flattens. This flattening of the curve shows that the process of automatization is very slow; the gains in speed and accuracy are steady but minimal. Why? The brain goes slowly when it comes to automatizing things, because anything we automatize – including mistakes – cannot be subsequently unlearnt (a phenomenon known as ‘fossilization’ in language learning).

The problem in much language learning in English schools at Key Stage 3 (beginner to intermediate stage) is that once the students evidence ‘mastery’, teachers often move to the next topic/grammar structure instead of providing automatization practice – what cognitive psychologists often refer to as ‘overlearning’.

Automatization as fluency

In language learning, automatization practice equals work on fluency, getting the students to use the target vocab and/or structures under communicative pressure and time constraints, what Johnson (1996) calls R.O.C.S (aka Real Operating Conditions). ROCs are ‘desirable difficulties’ (Bjork and Linn 2006) which pose variable demands on learners’ processing ability when performing the targeted behaviour or task, in resemblance with real-life conditions. Pedagogically speaking, the application of ROCs in LT results in task grading: manipulating different factors to vary the complexity of the tasks. Among them, Johnson (1996) highlights degree of form focus, time constraints, affective factors, cognitive and processing complexities.

Paul Nation calls this all-important dimension of language learning the ‘fluency strand’.

Figure 2: the fluency strand

Most teachers, partly because they feel under pressure to ‘cover the syllabus’ and partly because they are reassured by progress tests that their students ‘know’ the target L2 items neglect this area of L2 proficiency. Yet, automatization practice is key, because (1) it is essential for spontaneity; (2) what is automatized is never forgotten and (3) if fluency training aims – as it should – at automaticity across a range of linguistic contexts and tasks, it enables students to use what they have learnt more flexibly in real-life interactions.

Basically, tragically, practice with the target items ends exactly when it is needed the most ! And, more importantly, that practice is needed over a long period of time ( through distributed practice).

Automatization is more than speed of retrieval

This kind of training gets eventually the students not merely to fast retrieval which requires little or no conscious awareness (what psychologists call ‘ballistic processing’) but, more interestingly, produces qualitative changes in the way we retrieve and apply the vocab/structures we need to successfully execute the target task. In other words, automaticity means that the brain finds a more efficient way to produce that vocabulary and those structures in the context of a given task. We know this because MRIs show that when L2 learners have become fluent in the execution of a task, the brain areas activated during the execution of that task shrink, a sign that the brain makes less effort and needs to recruit fewer neural circuits. This qualitative change is called by researchers restructuring.

Main implications for language pedagogy

The main implications for language learning are obvious: we need to spend more time on automaticity (aka fluency) training. This means:

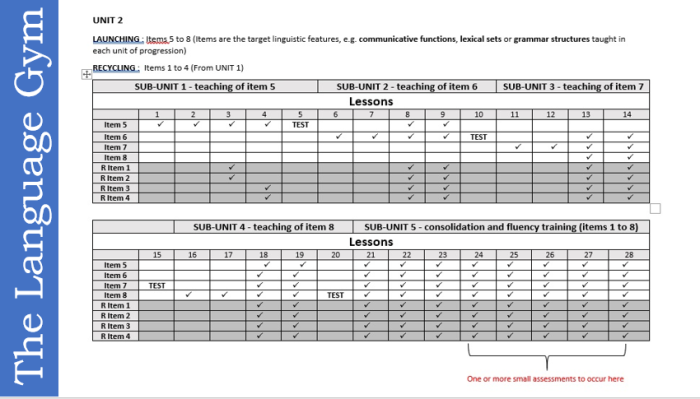

(1) cutting down the curriculum to allow for lots of recycling, task repetition and fluency practice once the students show they master the content of a unit of work. Textbooks go way too fast !

(2) lots of recycling and task repetition at regular intervals. These will be very close in time to each other at the beginning of the curve and gradually more distant as the curve flattens;

(3) deliberate work on fluency/automaticity, by increasing the communicative pressure and time constraints in the execution of tasks (e.g. the 4,3,2 technique, Messengers, Market place, Speed dating, my mixed-skill ‘Spot the difference’, etc.)

(4) ensuring that the same set of vocabulary and grammar structures are practised across different contexts, as learning is context and skill dependent (e.g. what is learnt in reading and listening is not transferred automatically to writing and speaking; what is learnt practising a task won’t be transferred to another, even though the two tasks are very similar).

(5) teaching chunks (e.g. sentence frames and heads), as it reduces cognitive load thereby speeding up processing and fluency. Teaching multi-word chunks means that there are fewer grammar rules (if any) to apply and automatize, as opposed to teaching single words that the learners must learn to bind together grammatically in real time.

The curriculum-design matrix in figure 3 below (aka the “Conti matrix”), makes provision for all of the above. As explained in previous posts, in my approach automatization occurs in the context of tasks designed to elicit language processing and production under what Keith Johnson calls R.O.C. (real operating conditions), i.e. in communicative drills and tasks I will discuss in greater detail in my next post.

Figure 3- The Conti Matrix

Practice with the language they KNOW

Of course, before venturing into this type of training, it is crucial that the students have mastered the target items, i.e. they can recall them with some ease and without the help of reference materials.

This is unfortunately one of the most common problems in much of the communicative language learning I have observed in 25+ years of teaching; the students are interacting orally, yes, but having way too often to resort to the help of word/phrase lists. When you stage fluency-development activities, the students shouldn’t need to do this. They should have had already plenty of retrieval practice which has weaned them off such lists first. That’s why, in my Recycling Matrix, the students get to the automatization phase at the very end of a macro-unit (i.e. unit 5).

Make time for fluency training

Some may object that there is not enough time for this type of training. My response is that it is all down to effective curriculum design and smart use of lesson time. But it is also dependant on your mission as a language teacher: are you imparting abstract knowledge of grammar structures or are you forging confident and effective L2 speakers ? Are you preparing students for exams or for real-life use? Are you teaching to cover the syllabus or for durable learning and spontaneity?

In the early years of language instruction, when exams are not and should not be a concern, you can and must make time for fluency practice. Focus on the target items and tasks you students truly must learn to perform confidently, spontaneously and as accurately as possible and cut down the superfluous.

Less is more.

You must be logged in to post a comment.