1. Listening to a lot of good-quality 90-to-95 % comprehensible input through activities which model speaking and recycle what you want your students to say many times over (input-flooding). This is the single most deficient and neglected dimension of speaking instruction (Conti and Smith, 2019). Most listening tasks in books and published materials do not model language – they test student on what they hear. That is why Steve Smith and I wrote our latest book.

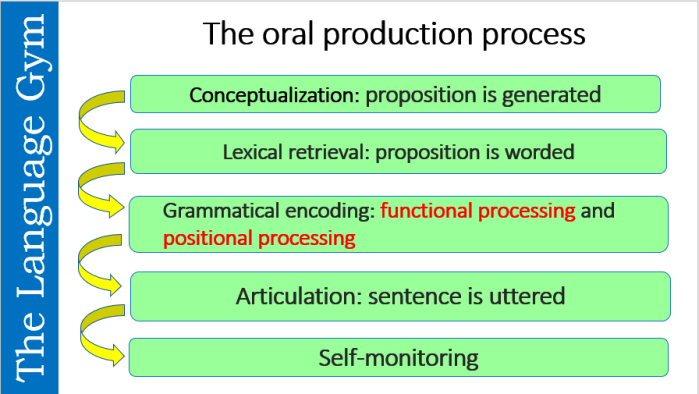

2.Understanding what processes speaking involves and targeting them through deliberate practice. So, what kind of speaking you do, not merely the quantity of it, is paramount. Ask yourself: what am I doing this speaking task for? Is it to focus on pronunciation, grammar/syntactic accuracy, fluency, complexity, effective communication, communication strategies etc.? Each purpose will shape the type of task you are going to stage.

3. Making sure students learn to chunk language. Model and teach language in chunks. The longer the stretches of language the students can produce in one go without breaks, the better (Wood, 2010). Pauses should occur at the end of each clause, not in the middle. If pauses occur in the middle of clauses, it may point to disfluency at some level of production, e.g. articulation, vocabulary retrieval issues, grammar/syntax issues, etc.(Segalowitz, 2010). Clause chaining appears to be one of the most effective strategies the human brain has developed in order to reduce cognitive load in fluent communication.

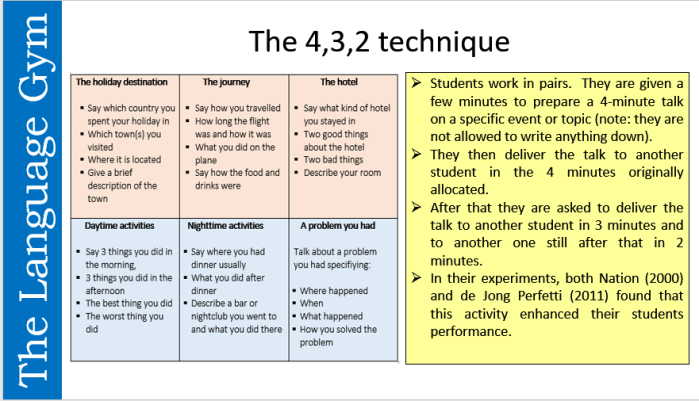

4. Task-repetition: we know that task-repetition leads to improvements in fluency (Bygate, 2015). Students benefit from task-familiarity even 9 weeks after the first execution of a task (Bygate, 2009).

5.Sequencing speaking tasks effectively. For instance: ensuring that an instructional sequence goes from highly structured to less structured production; from planned to unplanned production (the latter occurring very late in a sequence). That a series of listening tasks pave the way for a speaking activity.

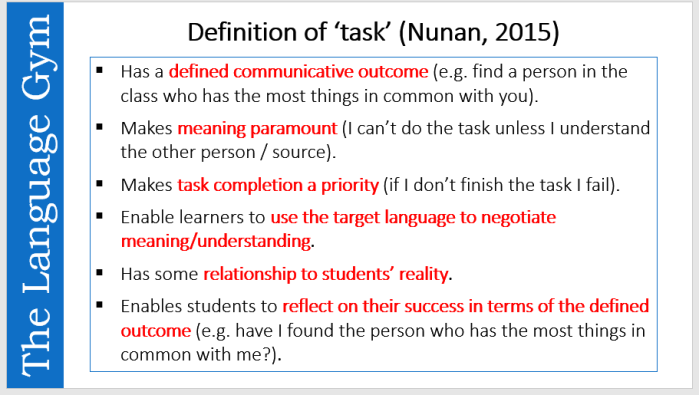

6.(this is possibly the most important bit) Preventing anxiety and nurturing the motivation to talk. Anxiety prevention: creating non-threatening opportunities for talking in a non-threatening and empathetic environment; preparing the students effectively for speaking tasks (we know planning reduces cognitive load); providing solid scaffolding for less confident learners (e.g. my prepping them for more challenging tasks through a series of pre-tasks; providing differentiation by support). Motivation-to-talk: avoiding the ‘so-what’ effect (so common in language classrooms), staging tasks which are engaging, FUN and have a clear purpose, possibly real-life like.

7. Specific training in the automatic retrieval of the target linguistic features, by, for instance, gradually increasing the time constraints and communicative pressure in which the students have to deliver the same talk (e.g. in tasks such as the 4,3,2 technique; Messengers; Market place; Speed dating; Ask and move tasks). This kind of fluency training which Paul Nation calls the “fluency strand” is possibly the most neglected, yet by far the most important.

8. Having classroom routines such as entry, register and exit routines which provide the students with opportunities for implicit learning and with attentional frames for sets of useful formulaic chunks/phrases. Make sure you scaffold each routine appropriately at the beginning to ensure nobody finds it threatening (e.g. put up a poster with key phrases by the door or a sentence builder on the classroom screen). Don’t correct, recast.

9.knowing when to go to production. Way too often students are asked to produce new language features beyond their current level of competence after insufficient receptive processing of and exposure to them through listening and reading. Yet, we know, that if students go to production to soon (e.g. the classic “repeat after me” on saying something for the very first time) you are likely to induce error and negative learning (de Jong, 2009). Provide plenty of receptive practice before you ask your students to speak and write.

10.Finally, the goals and content of your course is likely to impact the development of fluency. If your course content focuses mainly on grammar structures you are more likely to focus on the accumulation of intellectual knowledge and less on the building of fluent communication. If, on the other hand, as I do, your focus is on communicative functions, you are more likely to stage communicative tasks, which may result in greater fluency.

These are but a few of the most important – yet often neglected – facets of fluency training. To claim, as I read on certain blogs, that this or that activity promotes spontaneity is vague and unhelpful. Every single speaking activity, even repeating aloud, helps promote fluency and spontaneity to a degree.

However, it is not sufficient to make bizarre claims such as the one that Jenga blocks promote spontaneity, as I have read recently on a blog on the allegedly best way of teaching speaking. It is all too easy and random. One needs to be clear as to how, to what extent and, most importantly, which dimension of speaking competence that activity addresses.

In a nutshell: plan for spontaneity. Have a principled approach to it, possibly one rooted in research evidence, not hearsay or folklore. One which deliberately addresses as many of the above areas as possible.

To find out more about my approach to language teaching, get hold of our latest book “Breaking the sound barrier: teaching learners how to listen” co-authored with Steve Smith

You must be logged in to post a comment.