Introduction – What is Phonological Memory?

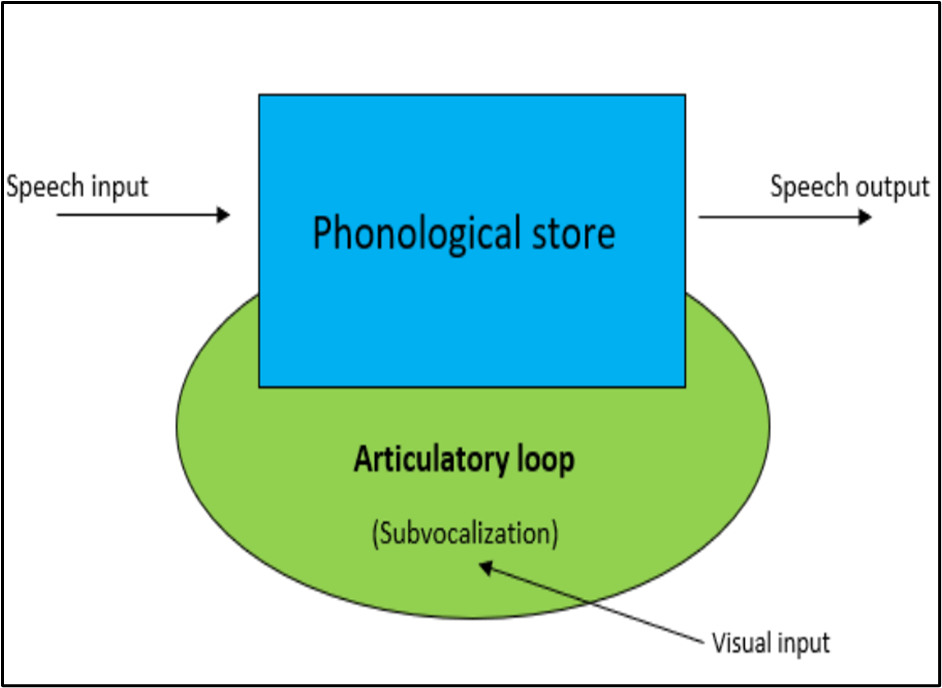

Phonological memory, often referred to as phonological working memory, is the ability to temporarily store and manipulate sound-based information. One of the most influential models of working memory, Alan Baddeley’s, conceives of Phonological Memory as an articulatory loop responsible for holding and rehearsing verbal information. Consider how you hold a word or phrase in your head as you make sense of it or prepare to say it; or how you say words in your head as you read from a book; or how you try to make sense of some spoken language. This would be impossible without phonological memory.

Figure 1: Phonological memory

Based on the above, it is obvious that this cognitive function is crucial in vocabulary acquisition for both first and second languages. The Phonological Loop interacts with long-term memory, playing a vital role in the long term retention of the phonological form (i.e. the sound) of new words and phrases. As new phonological forms are held in the phonological store during rehearsal, so more permanent memory representations are constructed. This is one reason why it’s so important to allow students to hear and repeat new language as often as possible. They need to have a phonological representation of words, not merely know what they mean or look like. This makes it easier for them to recognise words and chunks in the continuous stream of speech and to retrieve them in their oral form as they speak.

Research has consistently demonstrated a strong link between phonological memory and the ability to learn new words, evidencing that children with robust phonological memory tend to have larger vocabularies. This relationship suggests that the capacity to retain phonological information facilitates the learning of new words. In fact, individuals with stronger phonological memory capacities often exhibit more rapid and efficient L2 vocabulary learning. Neuroimaging studies have identified specific brain regions associated with phonological processing and vocabulary learning. The anterior surfaces of the supramarginal gyrus, for example, are closely related to phonological abilities, underscoring the neurological basis for the connection between phonological memory and vocabulary acquisition.

What is very interesting and extremely important for our learners is that when we read silently we tend to automatically activate the sound of the word in our heads (subvocalization). This means that the more fluent the students become in reading words and chunks of words aloud, the more efficient they will become at reading. It also means that if students do not have a correct phonological representation of a word, successful vocabulary and grammar learning will be impaired.

Vocabulary learning is mediated by sound

In other words, in language learning, memory for words is mediated by sound. Hence, with your beginner students, investing a lot of time and effort into learning the correct oral form of words is a must. This doesn’t mean merely focusing on phonics, as today’s trend goes, but also and more importantly, to learn vocabulary through listening.

The tragedy is that in many L2 classrooms, vocabulary learning does not occur mostly through listening and speaking as it should, but rather through reading and writing tasks on worksheets or Apps. Fortunately, deliberate training in phonological processing is becoming more frequent in many UK MFL classrooms through reading aloud and dictations, thanks to the washback effect of the new GCSE examination. However, more work needs to be done.

Even language gurus with doctoral degrees seem not to be in the loop when it comes to the importance of Phonological Memory training. In a CPD event not long ago, a prominent English language ‘guru’ asserted that Sentence Stealer (a chunking-aloud game designed to develop fluent phonological processing) was only a motivational gimmick with zero benefits for language learning. Based on the above and the below, though, it is obvious how Sentence stealer or any other chunking-aloud game or reading-aloud task can only be beneficial to phonological memory enhancement and, consequently, to vocabulary acquisition.

Implications for language pedagogy

The most consequential implication for our students is that we need to help them make their phonological memory work as fast and accurately as possible. Those of you who are familiar with EPI will know how the approach tackles this issue through the following techniques:

- Phonological awareness activities such as, ‘Faulty echo’, ‘Write it as you hear it’, Rhyming pairs’ etc.

- Scripted listening games such as ‘Spot the Intruder’, ‘Break the flow’, ‘Sentence bingo’, etc.

- Aural (L2 to L1) sentence and word recognition tasks such ‘Faulty translation’, ‘Gapped Translation’, ‘Tick or cross’, etc.

- Chunking aloud games such as ‘Sentence Stealer’, ‘Mind reading’, ‘Lie detector’, etc.

- Shadow reading

- Dictations

- Oral (L1 to L2) retrieval practice games such as ‘Oral ping-pong’, ‘No snakes no ladders’, ‘Translation face-off’ , etc.

- The vocab trainer, the Listening trainer and the audio-boxing game on www.language-gym.com or any other internet-based resource teaching vocabulary aurally

- Role plays, Information-gap activities and any other communicative task

Understanding the role of Phonological memory: the research evidence

Understanding the role of phonological memory in vocabulary learning is key in view of its centrality to second language acquisition. Teaching methods and remedial interventions aimed at enhancing phonological memory, such as phonological awareness training and specific aural and oral tasks , can lead, as we have just discussed, to improved vocabulary acquisition, particularly in language learners and individuals with language impairments.

Here is how phonological memory affects language acquisition:

1. Vocabulary Acquisition and Retention:

- Phonological memory enables temporary storage of sound sequences, which is essential when learning new words in a foreign language.

- It helps in mapping unfamiliar sounds to meanings, facilitating the initial stages of vocabulary learning.

- Research Evidence:

- Gathercole and Baddeley (1990) found a strong correlation between phonological memory capacity and vocabulary size in children learning a second language.

- Papagno & Vallar (1995) demonstrated that individuals with better phonological memory acquired foreign words more efficiently.

2. Pronunciation and Phonetic Learning:

- Phonological memory aids in retaining unfamiliar phonetic patterns, which is crucial for accurate pronunciation and intonation.

- It supports the repetition and rehearsal of new sounds, leading to better pronunciation and phonological awareness.

- Research Evidence:

- Speciale, Ellis, and Bywater (2004) found that learners with stronger phonological memory produced more accurate pronunciation in L2.

- Service (1992) showed that phonological memory predicted L2 pronunciation skills among Finnish students learning English.

3. Grammar and Syntax Acquisition:

- Phonological memory allows learners to temporarily hold and manipulate language structures, facilitating the understanding of complex grammatical rules.

- It helps in processing and recalling sentence patterns, contributing to syntactic development in L2.

- Research Evidence:

- Williams and Lovatt (2003) found that phonological memory capacity was linked to better acquisition of grammatical rules in artificial language learning tasks.

- Ellis and Sinclair (1996) demonstrated that learners with stronger phonological memory showed superior performance in learning L2 syntax.

4. Listening Comprehension and Fluency:

- Phonological memory enables learners to retain spoken information long enough to comprehend and process meaning.

- It contributes to speech segmentation, allowing learners to distinguish words and phrases in continuous speech.

- Research Evidence:

- Masoura and Gathercole (1999) showed that phonological memory predicted listening comprehension skills in Greek students learning English.

- Service and Kohonen (1995) found that students with better phonological memory were more fluent and accurate in spoken L2.

5. Reading and Writing in L2:

- Phonological memory supports phoneme-grapheme mapping, aiding in reading new words.

- It helps in spelling and writing by maintaining the phonological structure of words during transcription.

- Research Evidence:

- Dufva and Voeten (1999) found that phonological memory predicted reading comprehension in L2 learners.

- O’Brien, Segalowitz, Freed, and Collentine (2006) showed that strong phonological memory correlated with better writing performance in L2.

6. Overall Cognitive Load Management:

- Learning an L2 involves increased cognitive load due to unfamiliar vocabulary and grammar structures.

- Phonological memory reduces cognitive load by temporarily storing information, allowing for more complex language processing.

- Research Evidence:

- Baddeley, Gathercole, and Papagno (1998) illustrated that phonological memory helps in reducing cognitive overload, thus supporting more efficient L2 learning.

Concluding remarks

Phonological memory plays a fundamental role in second language (L2) acquisition, influencing virtually every aspect of language learning, from vocabulary acquisition to pronunciation, grammar, listening comprehension, and even cognitive load management. Its importance stems from its capacity to temporarily store and process sound-based information, allowing learners to map new phonological forms to meanings, rehearse unfamiliar sounds, and build accurate phonological representations. Without this cognitive mechanism, it would be challenging for learners to retain new words, accurately pronounce sounds, or comprehend spoken language.

The evidence is compelling: research consistently demonstrates that stronger phonological memory is associated with larger vocabularies, better pronunciation, enhanced grammatical understanding, and improved listening and reading comprehension. Studies by Gathercole and Baddeley (1990), Papagno & Vallar (1995), and Service (1992), among others, highlight the positive correlation between phonological memory and successful L2 learning outcomes.

For language educators, the implications are clear: teaching strategies must prioritize activities that stimulate and strengthen phonological memory. This includes phonological awareness exercises, chunking aloud games, oral retrieval practice, scripted listening tasks, and interactive role plays that encourage repetitive hearing and production of language. By focusing on the auditory and articulatory aspects of language learning, teachers can help students internalize the phonological structures needed for fluent and accurate communication.

Moreover, understanding that vocabulary learning is mediated by sound underscores the need to balance listening and speaking activities with traditional reading and writing tasks. Ensuring that students not only understand the meaning of words but also possess a clear phonological representation of them enhances both recognition and recall, fostering greater fluency in both spoken and written forms.

Ultimately, phonological memory is not merely a supportive component of language learning but a driving force that shapes the way learners perceive, process, and produce language. By leveraging this knowledge, educators can create more effective and cognitively aligned learning environments, maximizing their students’ potential to acquire a second language efficiently and proficiently.

You must be logged in to post a comment.