Introduction

Designing a Modern Foreign Languages (MFL) curriculum is a complex process that requires careful planning and consideration. However, many curriculum designers fall into common pitfalls that hinder effective language learning.

Below are some of the most frequent errors I have identified over the last ten years of curriculum consultancy, during which I helped over 700 schools enhance their curriculum provision.

For those of you who would like to further their knowledge and understanding of the issues below by consulting the relevant literature, I have added references at the bottom of this article. You may, of course also attend my workshops, which you can find here: www.networkforlearning.org.uk in which I address every single one of the problem areas below.

Key shortcomings in Curriculum Design

1. Lack of Consideration of the Specific Lacks, Wants, and Necessities of Learners

This is one of the most common mistakes and a very serious one. We know that the more aligned a curriculum is with the lacks, wants and necessities of our students, the more likely it is to succeed (Nation and Macalister, 2010). Relevance to the learners is one of the key predictors of a language curriculum’s success (Taylor and Marsden, 2012).

Sadly, in my experience, curriculum design often fails to account for the diverse needs of learners, resulting in a one-size-fits-all approach that does not address their specific linguistic goals. Language learners come with varying levels of prior knowledge, different motivations, and unique learning preferences. When these factors are ignored, the curriculum may be either too advanced or too simplistic, leading to disengagement and frustration (Brown, 2009).

This is very common in many schools I visit, especially those which:

(1) base their curriculum on a textbook. Textbooks are not designed with the specific needs of your learners in mind, especially if your children are from a lower socio-economic stature and/or a diverse religious and ethnic background

(2) belong to a government, trust (e.g. UK) or other organization where there is a centralised curriculum

Example: within the same U.K. academies trust, the latter bases its centralised curriculum on the schemes of learning of a school in a predominantly ‘white’, fairly affluent area, even though many schools are located in very diverse, underprivileged areas.

Solution: Conduct a needs analysis through surveys, interviews, and proficiency tests to determine learners’ goals and requirements (Graves, 2000). If you are in secondary, liaise with the primary feeder schools in your area to find out as much as possible about your future year 7 students. Try to make the content of your curriculum as relevant to the students as possible based on your findings. In schools I worked at, we would ask the students through a Google form or classroom discussions, ahead of teaching a unit, what words they were interested in learning on a given topic or what scenario they would like to learn the new topic in (e.g. in the topic of talking about the recent past, my students on one occasion chose ‘An outing to a cinema’ and ‘A birthday party I went to’ over other options). If your students are from a lower socio-economic status and/or have low literacy levels, teaching a grammar-rich curriculum may not be a good idea. If your students’ levels of motivation to learn languages are historically low, what can you do to ignite their motivation? You may need to include more gamification; scaffold instruction more carefully and prioritize oracy. If they come from an area where xenophobic attitudes are rife, you may need to dispel negative stereotypes about the target-language country through a number of curricular and extracurricular initiatives. If your students are not generally good at retaining information how can your address that through your short-, medium- and long-term planning? You may have to strip down your curriculum of the superfluous and multiply the recycling opportunities. If you have the stomach, do create your own booklet tailor-made for your student population, rather than work from a textbook. Many schools in the UK are doing this very successfully.

2. Lack of Consideration of the Learning Context

A curriculum that does not align with the learning environment often fails to be effective. The resources available, the frequency of instruction, the socio-economic status of your students, the mission and core values of your school, the national curriculum, the classroom space available, the cultural background of the learners, the colleagues you work with, the language you are teaching etc. all influence how well your students can acquire a new language. A curriculum designed for an immersive setting may not work well in a setting with limited exposure to the target language, leading to unrealistic expectations (Nation & Macalister, 2010).

Example: A curriculum based on grammar-translation designed for an expensive private school in Switzerland with highly motivated and well-behaved upper middle-class children, may not work as well in a deprived inner-city area school in London with serious behavioural challenges.

Solution: conduct a thorough SWOT analysis of the hurdles to successful learning in your environment. Consider the top five factors that work against you and ask yourself: does your curriculum actually tackle those issues? E.g: if, historically, motivation is low, has your curriculum been designed with an eye to be as engaging, relevant and self-efficacy building as possible? If your students only see you one hour a week, are you sure that you can sustain the pace dictated by the textbook? If not, what are you going to prioritise? How are you going to recycle it? With what frequency ? As far as the language being taught is concerned, let me point out another very common mistake: the ‘translation’ of a curriculum from one language into another with identical or near-identical objectives, outcomes and pace. This is not a massive mistake when one is adapting a Spanish curriculum to Italian. It is, however, a serious mistake when one demands that L2 learners of Mandarin or Russian achieve in one term what learners of French or Spanish do. Sadly, I have seen this play out quite a few times in Academy Trusts around the UK.

3. Too Many Objectives

This is another very common and serious issue which I observe in nearly every single school I visit. As Confucious one said, if one runs after too many chickens, one will catch none. With only a couple of hours’ contact time a week, one needs to be realistic and prioritize what is more and less important for the learners.

Overburdening a curriculum with too many learning objectives can result in rushing through content which in turn will likely cause cognitive overload, where learners struggle to retain and apply new information. A curriculum that attempts to cover too much within a short time often sacrifices depth for breadth, leaving students with fragmented knowledge that lacks real-world applicability (Richards, 2001).

Example: A course that tries to cover all the grammar content in a typical Pearson or OUP textbook in one year may lead to students memorizing rules but failing to apply them in spontaneous conversation or writing.

Solution: Prioritize key competencies and distribute learning objectives across different stages of the course. Focus on high-frequency structures first and reinforce them before moving on to more complex grammar. Implement mastery-based progression, ensuring students have grasped a concept before moving on. Use spaced repetition techniques to reinforce previously learned concepts.

4. Fuzzy Goals

This is the most serious error of all. As Nation and Macalister’s (2010) model below (Figure 0) shows, goals sit right at the heart of the curriculum design process. Hence, they need to be as laser-focused as possible, as unclear learning objectives make it difficult for students and teachers to track progress effectively. Goals that lack specificity often lead to instructional inconsistencies, where teachers may interpret and teach content differently. This can result in learners missing critical skills necessary for their language development (Dörnyei, 2005).

Figure 0 – Nation and Macalister’s (2010) model of curriculum design. The curriculum goals sit at the centre of the curriculum design process and are informed by principals, learner needs and the learning environment.

Look at the learning objective and outcomes you currently set in your department for each of the four skills for each and every term: are they detailed enough for anyone reading them to have a very clear and thorough understanding of what a child is expected to know and do, from the vocabulary, grammar, phonics, intercultural skills and learning strategies they need to master, to the tasks in which they are expected to use them? Is it explicitly stated whether the learning of a specific grammar point will reach the level of awareness, intermediate mastery, deep mastery or automaticity? If not, how will Ms Roberts know to what extent Mr Jones’ students now in her year 10 class have acquired the core grammar taught from year 7 to 9?

Example: ‘By the end of year seven, an average student at XXX School is expected to be able to understand the gist of AURAL and WRITTEN texts, containing familiar and unfamiliar language’ is a vague outcome. Compare it with the statement in Figure 1 below

Figure 1: Example of a well-articulated learning outcome

Solution: Use SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound) objectives. Ensure that the way your articulate your objectives and outcomes is as laser-focused, detailed and clear as humanly possible.

5. Imbalance of the Four Strands

A well-balanced MFL curriculum should equally address understanding meaning, communicating meaning, focus on form (grammar and phonics), and fluency. Many curricula have the following deficits in this area:

(1) they disproportionately focus on grammar drills or rote vocabulary memorization while neglecting communicative competence, resulting in learners who can understand written text but struggle to speak or listen effectively (Nation, 2007).

(2) they do not include a solid fluency strand, which means that the core vocabulary and grammar is not learnt to a level of automaticity which makes its retention durable and its availability in the aural/oral skills possible.

(3) listening, the most challenging skill, especial in the GCSE and A-Level exams, is not practised sufficiently

Example: Students who can conjugate verbs in writing but hesitate to form basic spoken sentences.

Solution: Ensure lessons integrate listening, speaking, reading, and writing while maintaining an equal focus on meaning, form, and fluency. Design activities such as role-plays, interactive listening tasks, and communicative writing exercises to promote holistic language development. Use task-based learning to encourage real-world language use.

Figure 2 – Paul Nation’s four strands

6. Inadequate Integration of vocabulary, grammar and phonics

When vocabulary, grammar, and phonics are taught in isolation rather than in context, learners struggle to apply their knowledge not only in real-world scenarios but also in exams where they are required to perform under great pressure (especially in listening and speaking). For instance, students may learn a set of vocabulary but fail to use them in grammatically correct sentences, leading to poor practical language use (Ellis, 2008) or they may learner grammar rules without using them with a substantive range of vocabulary.

Quite a few schools I have collaborated with recently were making the mistakes of teaching towards the new GCSE treating Vocabulary, Grammar and Phonics as three self-standing entities. This is becoming quite common due to the new English GCSE, where teachers feel their students need to memorize the mandated word lists in order to pass the exam. However, such words must be learned in context and across all four language skills in order to be useful on the day of the exam!

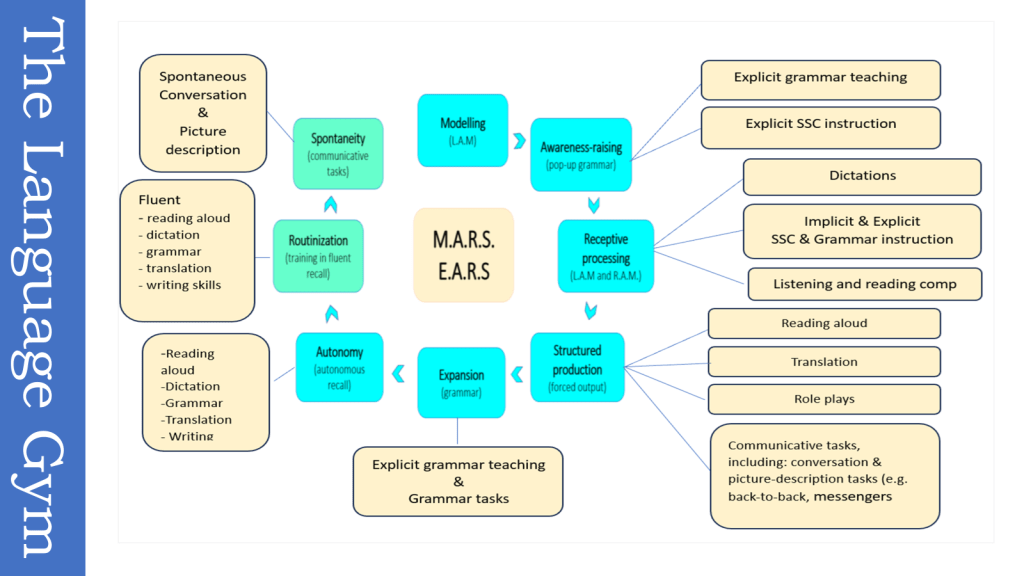

Figure 3: Integration of Vocabulary, Grammar and SSC (phonics) within the MARS EARS sequence

Example: A student learns vocabulary in a list but cannot use them correctly when forming sentences in conversation.

Solution: The best way to integrate Vocabulary, Grammar and Phonics is by designing input-to-output sequences in which these three ‘pillars of progression’ are modelled and practised in context across all four language skills in a scaffolded fashion (e.g. the MARSEARS and the PIRCO sequences)

Figure 4 – The PIRCO sequence is the input-to-output sequence adopted in EPI at KS4 (14 to 16 year olds).

7. Random Selection of Grammar and Vocabulary

The selection of grammar and vocabulary should not be random as it might

(1) fail to generate motivation to learn (relevance being key in this regard)

(2) dent learner self-efficacy (by being beyond the current grasp of the learners)

(3) have little surrender value

Solution: select language items which are likely to generate interest on the learners’ part (the principle of relevance); also select high-frequency items (remember that the top 2,000 words in a language give access to 85% of any generic text); finally, consider learnability issues (see point 8 below).

8. Selection of Grammar Without Considering Developmental Readiness

Selecting grammatical structures and vocabulary without a logical sequence can hinder students’ ability to build upon previously learned content. If learners encounter advanced structures before they have mastered basic ones, they may become confused and demotivated (Pienemann, 1998). This point refer to the issue of learnability (see this post), e.g.: are my L2-French learners ready in year 8 to learn the full conjugation of the perfect tense in ETRE or Reflexive verbs? Most likely no because they often cannot even conjugate the present tense of ETRE and have not mastered the basic rules of agreement (in spontaneous production at least).

Example: Teaching conditional sentences before students have fully grasped past and present tenses.

Solution: Follow a logical sequence based on frequency of use and communicative necessity. Implement structured syllabus planning where new grammar and vocabulary items build progressively upon previously learned concepts. Consider the factors (e.g. cognitive load, L1 negative transfer, element interactivity) which make the learning of a grammar structure challenging.

9. Insufficient Scaffolding

This is the second most serious mistake of all: without adequate scaffolding, students become overwhelmed and lack the confidence to engage with the language meaningfully. Effective scaffolding gradually reduces support as learners gain proficiency (Vygotsky, 1978). This means that every phase in an instructional sequence that moves from modelling to receptive practice and from the latter to production, needs to build on the previous one following the formula: ‘what the learners know + 1‘.

Sadly, most textbooks do not do this; in a two-page sub-unit, they cover the same vocabulary across all four language skills with zero scaffolding! Since many MFL departments base their schemes of learning on textbooks operating this way, it is not surprising that many language learners lose motivation by the end of the first year of language learning.

Solution: Make sure that you design instructional sequences with an intensive modelling and receptive phase first. With beginners, you should devote one or more lessons entirely to listening and reading in order to first establish solid receptive knowledge. Go to production only when you feel the students are ready, scaffolding speaking and writing adequately starting with highly structured tasks and gradually moving to freer ones. You do not have to cover all four language skills; in many cases such practice does more harm than good.

10. Content Overload and Inadequate Recycling

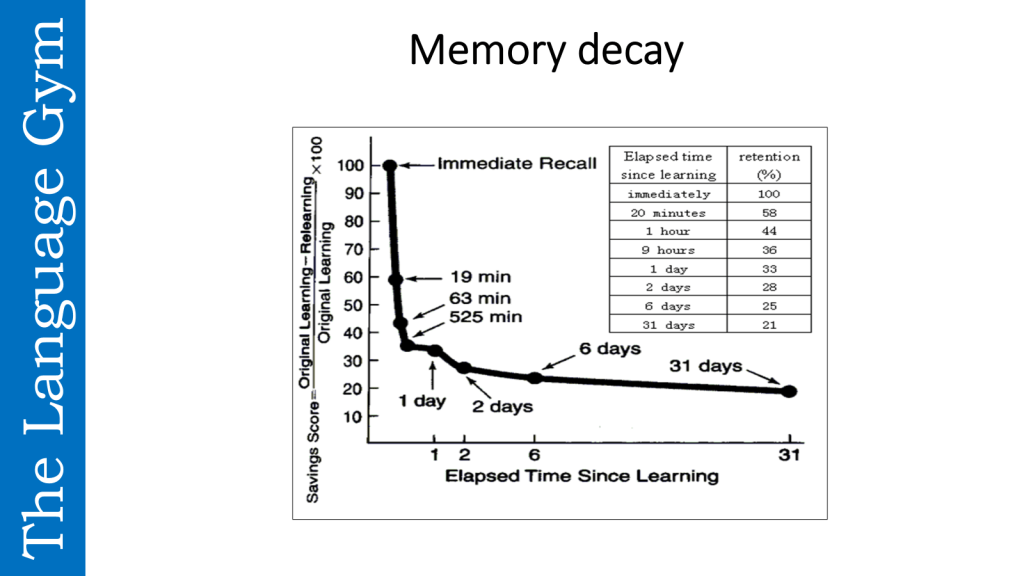

This is possibly the third most serious mistake I encounter in my curriculum consultancy work. When too much content is covered we create at best surface-level learning rather than deep mastery. Vocabulary requires masses of recycling in order to be acquired and most information we learn (around 67%) is lost after one day from initial learning. Also, since memory is context-specific (the TAP phenomenon), vocabulary needs to be recycled across as many contexts as possible in order to be truly useful and as multimodally as possible.

There are serious misconceptions about the amount of recycling required in order to learn a word amongst many language educators in the UK. Not long ago I watched a video-recorded session of a CPD session on curriculum design at a Teacher Talk Radio event in Manchester delivered by a seasoned MFL consultant, in which she asserted that learning a word requires six repetitions/encounters. Truth is: students may need 40 meaningful encounters at least across all four language skills, at least 7 to 10 through reading, 10 to 16 through listening, about 20 to 40 through the oral and written media. If a veteran consultant – who incidentally also happens to be a school inspector and a former principal – believes that all you need in order to learn a word is six repetitions…

Figure 5: the Ebbinghaus curve illustrates how fast the brain forgets newly-learnt information. The rate is likely to be higher when it comes to more complex grammar structures

Example: the books Vivo, Studio and Dynamo cover way too much grammar for students at that level of proficiency to master deeply enough for them to retain it durably and provide insufficient recycling, especially through listening and speaking, where 10-15 and 20-40 encounters are required, respectively for learning.

Solution: Plan for at least 40 encounters across all four language skills in the first instructional sequence devoted to a set of new language items, then revisit and review said items following a well-planned schedule over the weeks and months to come, gradually spacing out retrieval episodes.

11. Assessment Overload and Overreliance on Summative Assessment

Too many assessments can lead to test fatigue and stress while taking away valuable instructional time. Over-assessment often results in a focus on test performance rather than meaningful learning (Black & Wiliam, 1998).

When assessment is focused primarily on summative tests, students miss opportunities for ongoing feedback that supports learning. Summative assessment alone does not provide insights into students’ progress throughout the course (Harlen, 2007). Summative assessments, especially high-stake ones at the end of term, can be particulalry harmful with less able and motivated younger learners, who are the ones we want to include and win over!

Example: A curriculum that requires students to take weekly grammar tests, oral exams, and written essays, leaving little time for communicative practice.

Solution: Reduce summative assessment to the minimum and increase the amount of regular low-stake formative checks using mini whiteboards (e.g. quickfire translations or Q &As); through observations of student pairwork; surveys; self-reflection journals and peer assessments. Reduce high-stakes exams and incorporate more diverse and meaningful forms of assessment that measure language use in real-life situations.

13. Lack of Systematic Curriculum Evaluation

A curriculum that is not periodically reviewed and updated may become ineffective over time. Without evaluation, instructional gaps may persist, and best practices may not be incorporated (Richards, 2017). The data obtained through regular summative and formative assessment are useful but not sufficient.

Example: A common phenomenon I observe in the schools I work with is the fact that the students need to be re-taught in year 10 (4th year of secondary education in the UK) many of the fundamental grammar structures already taught in the previous years. It is obvious that if that is the case for several years running, that there is something majorly wrong with the curriculum that needs to be addressed.

Solution: Conduct regular feedback sessions with teachers and students, analyze performance data, and update the curriculum accordingly. Ensure that curriculum changes reflect new research findings and evolving language learning needs. You should ideally do a formal curriculum evaluation at the end of each term if you are introducing a new curriculum plan, where you triangulate various sources of data, e.g. student voices; test results; teacher feedback; students’ output in books and portfolios.

14. Lack of Intentional Design for Learner Self-Efficacy

Learner self-efficacy or can-do attitude plays a crucial role in motivation and language acquisition. In fact, according to Oxford Univeristy’s professor Macaro, it is the strongest predictor of language learning success (Macaro, 2007). If a curriculum does not build self-efficacy, the learners will disengage from the learning process (Bandura, 1997).

Many of the issues I have pointed out so far, especially inadequate scaffolding, content overload, poor recycling, selecting content the students are not developmentaly ready for and over-assessment undermine student self-efficacy.

Example: engaging your students with an aural text which is well below the 95% comprehensibility threshold without a substantive pre-listening phase familiarising it with the unknown vocabulary

Solution: since self-efficacy is the strongest predictor of language learning success, try to design a curriculum which puts the development of learner self-efficacy first. Imagine a curriculum where your main preoccupation is ensuring that the vast majority of your students develop a strong belief that they can indeed master the target language. Would such a curriculum look different from the one you are currently teaching? At the end of each term, administer a survey to find out how self-efficacious your students feel.

Figure 6 – in 2015 The Guardian reported the results of a survey as to why language learners drop languages at GCSE. The data clearly point to a self-efficacy deficit

15. The MFL team does not share a common set of pedagogical principles

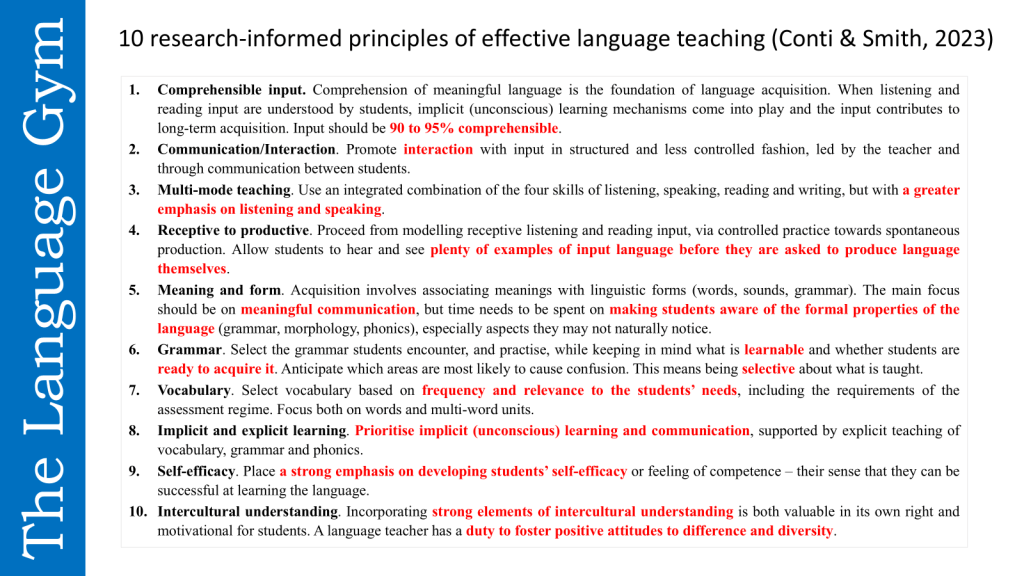

Very rarely have I come across an MFL department where the team shared a common set of non-negotiables pedagogical principles. How can teaching be consistent across a Dept without a common set of principles?

Solution: adopt a set of evidence-based principles which, whilst being non-negotiables, do not stifle teacher creativity. See the ones in the table below, from Smith and Conti (2023)

Figure 7

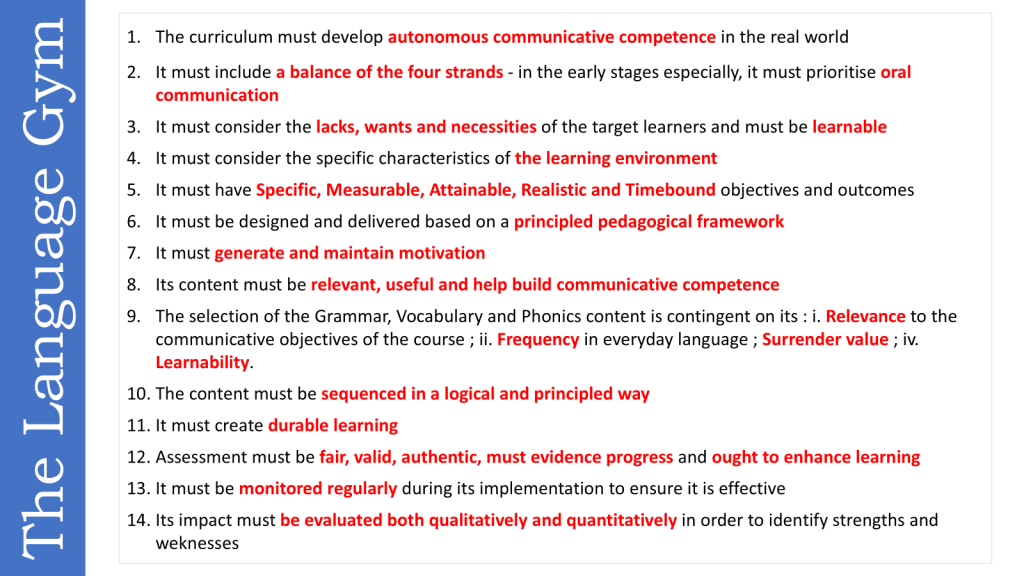

Principles of effective curriculum design

Figure 8 below, lists 15 evidence-based principles for effective curriculum design, based on my review of the relevant literature. With your current language curriculum in mind, which areas do you believe you need to address? Which ones are the top 3 that you may need to prioritize?

Figure 8 – Curriculum Design principles

Conclusions

Designing an effective MFL curriculum requires careful planning, evidence-based approaches, and continuous evaluation. The pitfalls outlined above can significantly impact language acquisition and student engagement, leading to frustration and poor retention of material. By addressing these common errors, educators can create a curriculum that fosters meaningful communication, encourages engagement, and ensures long-term retention of language skills.

A well-designed curriculum should balance linguistic skills, integrate key learning strands, scaffold learning effectively, and focus on the needs of the learners. In addition, formative assessments and continuous reflection should be embedded into the learning process to support student progress.

Ultimately, a successful MFL curriculum is one that prioritizes accessibility, motivation, and real-world applicability. By systematically addressing these common issues, educators can ensure that students not only learn a language but also develop the confidence and fluency necessary for real-world communication.

By addressing these common errors, MFL curriculum designers can create more effective, engaging, and supportive language-learning experiences that lead to real proficiency and long-term retention.

References

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 7-74.

- Brown, H. D. (2009). Principles of language learning and teaching. Pearson Education.

- Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D. M., & Goodwin, J. M. (2010). Teaching pronunciation: A course book and reference guide. Cambridge University Press.

- Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Ellis, R. (2008). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford University Press.

- Graves, K. (2000). Designing language courses: A guide for teachers. Heinle & Heinle.

- Harlen, W. (2007). Assessment of learning. Sage.

- Nation, P. (2007). The four strands. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1(1), 1-12.

- Pienemann, M. (1998). Language processing and second language development: Processability theory. John Benjamins.

- Richards, J. C. (2017). Curriculum development in language teaching (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

You must be logged in to post a comment.