1. Introduction Let’s face it—language learning is a messy, multi-layered business. It’s not just about memorising vocabulary lists or drilling verb conjugations. Beneath the surface, there’s a tangle of mental gears whirring away: memory, attention, logic, emotion, and more. And while we’d love to think that anyone can master a new language through sheer willpower and good teaching, the reality is more complex.

One factor that consistently crops up in the research? Intelligence—or more specifically, IQ. In this post, I’ll explore the sometimes uncomfortable questions:

- Does having a high IQ really give you an edge in instructed second language acquisition?

- Does a low IQ prevent you from being successful?

- If so, what are the implications for the classroom?

Language learning being a complex, multifaceted cognitive process influenced by a combination of innate ability and environmental factors, the answer is not that simple. In the below, I will deep dive into the literature on the topic in search for a solid and research-based account of the way in which IQ impacts second language learning.

2. Language Aptitude, Attitude, and IQ

Before we zoom in on how IQ shapes specific language learning abilities, it’s worth stepping back and looking at two key concepts that often get tangled up: aptitude and attitude. They might sound similar, but they pull the learner in very different ways—and understanding how IQ relates to both helps set the stage for the rest of the discussion. They aren’t just academic terms—they’re at the heart of what makes learners tick. And for us language teachers, understanding how they relate to IQ can change the way we approach planning, feedback, and support in the classroom.

Language aptitude and attitude are distinct yet complementary constructs in second language learning. Language aptitude refers to a learner’s cognitive ability to acquire language, including phonemic coding, grammatical sensitivity, inductive language learning, and memory. In contrast, language attitude encompasses a learner’s emotional and motivational disposition toward the target language, its speakers, and the learning process (Gardner & Lambert, 1972). Recent large-scale studies (e.g., Dörnyei & Skehan, 2003) have shown that aptitude encompasses a wide range of abilities including memory for language sounds, grammatical sensitivity, and the ability to infer language rules quickly. It’s not fixed in stone, but it tends to be relatively stable. Learners with high IQ tend to score better on aptitude tests, especially those involving reasoning and memory.

Figure 1 – Skehan’s (1998) model of language aptitude

While IQ is more closely related to aptitude—particularly the analytical and memory-based components—it plays little direct role in shaping attitude. Research by Skehan (1998) and Carroll (1990) has emphasized that aptitude is partly heritable and largely cognitive, aligning closely with IQ. Attitude, however, is more influenced by sociocultural context, personal experiences, and affective factors. Importantly, high aptitude may enhance performance in formal learning environments (especially where the curriculum is grammar-heavy), but positive attitude is often a stronger predictor of sustained effort and long-term success, especially in immersive and communicative settings.

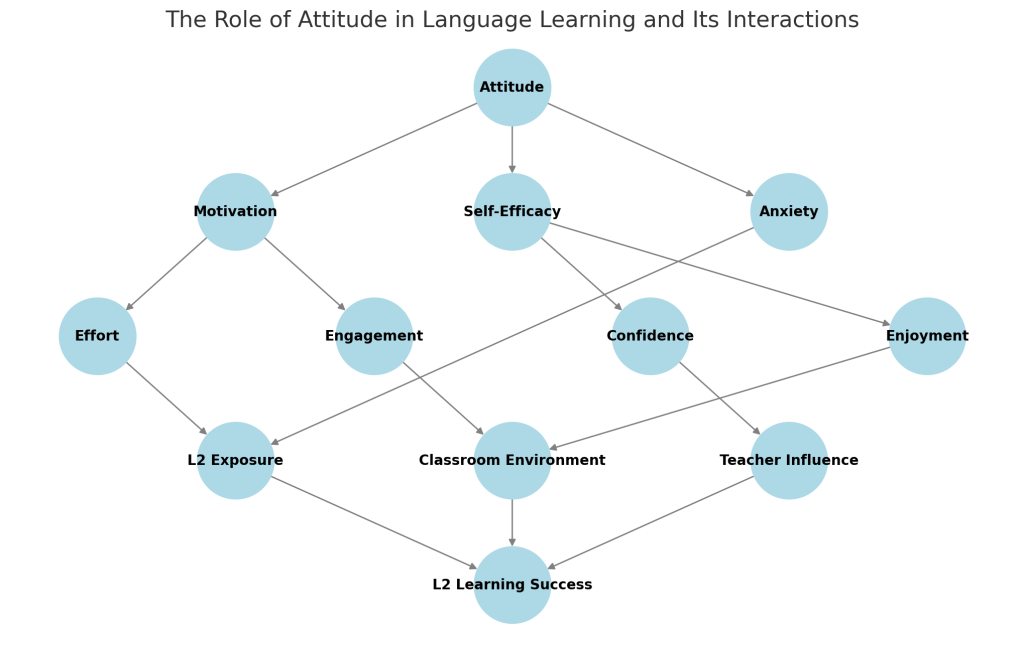

Figure 2: A visual representation of the role of attitude in language learning and how it interacts with various factors. The diagram illustrates: Attitude influencing motivation, anxiety, and self-efficacy, which shape learning behaviors. Motivation leading to effort and engagement, essential for L2 exposure. Self-efficacy boosting confidence and enjoyment, which affect classroom interaction. Classroom environment, teacher influence, and L2 exposure contributing to L2 learning success. This aligns with Dörnyei’s (2005) L2 Motivational Self System and Gardner’s (1985) Socio-Educational Mode

Understanding the interplay between aptitude, attitude, and IQ is essential for educators designing second language instruction. It is also crucial in light of research connecting IQ with socio-economic status. Studies such as those by Nisbett et al. (2012) and Sirin (2005) indicate that learners from lower-SES backgrounds are statistically more likely to score lower on IQ and aptitude tests—not necessarily due to innate ability, but due to factors like reduced exposure to literacy, nutrition, and educational opportunities. This raises important questions about equity and access in language education. Learners with high IQ may benefit from structured grammar and vocabulary tasks, while those with high motivation and positive attitudes may excel in communicative tasks—even if their cognitive aptitude is average, as attitude drives engagement, effort, and resilience in the face of setbacks. Gardner (2010) and Masgoret & Gardner (2003) found that motivation and positive attitudes often predict long-term language achievement more strongly than aptitude—particularly in less structured, immersive learning environments. A balanced approach that nurtures both dimensions can therefore optimize outcomes across diverse learner profiles.

2. Cognitive Dimensions Influenced by High IQ

2.1 Pattern Recognition

High-IQ individuals tend to excel at identifying patterns, a skill that underlies grammatical inference and syntactic comprehension. Pattern recognition facilitates faster internalization of rules governing sentence structure and morphological changes. Studies have shown that individuals with higher IQs often demonstrate superior abilities in recognizing linguistic patterns and structures. For example, Rostami et al. (2013) found a significant positive correlation between general intelligence and success in acquiring vocabulary and grammar among EFL learners.

2.2 Working Memory

Working memory is the capacity to hold and manipulate information over short durations—a function vital to real-time language comprehension and use. High IQ is frequently associated with enhanced working memory capacity. In their seminal work, Baddeley and Hitch (1974) first conceptualized working memory as a core component of language processing, highlighting its role in temporarily storing and processing linguistic input. More recently, Miyake and Friedman (1998) demonstrated that working memory capacity strongly predicts success in second language acquisition, particularly in mastering syntax and vocabulary.

2.3 Processing Speed

Faster cognitive processing enables learners to decode and respond to linguistic input with greater efficiency. This is especially beneficial for tasks involving listening comprehension and conversational fluency. In a fascinating study, Sheppard and Vernon (2008) established a clear link between processing speed and intelligence, indicating that faster processors tend to achieve better outcomes in language learning. Similarly, Kail and Salthouse (1994) demonstrated that processing speed supports various cognitive functions that are essential in second language acquisition.

2.4 Metalinguistic Awareness

Metalinguistic awareness—the ability to reflect on and manipulate language as a system—is often more developed in individuals with high IQ. This skill facilitates the recognition and correction of errors and supports abstract rule learning. In a very insightful study, Bialystok and Ryan (1985) found that high-IQ children exhibited superior abilities in detecting and correcting grammatical errors. Gombert (1992) further emphasized that metalinguistic development plays a crucial role in formal language instruction, particularly in structured learning environments.

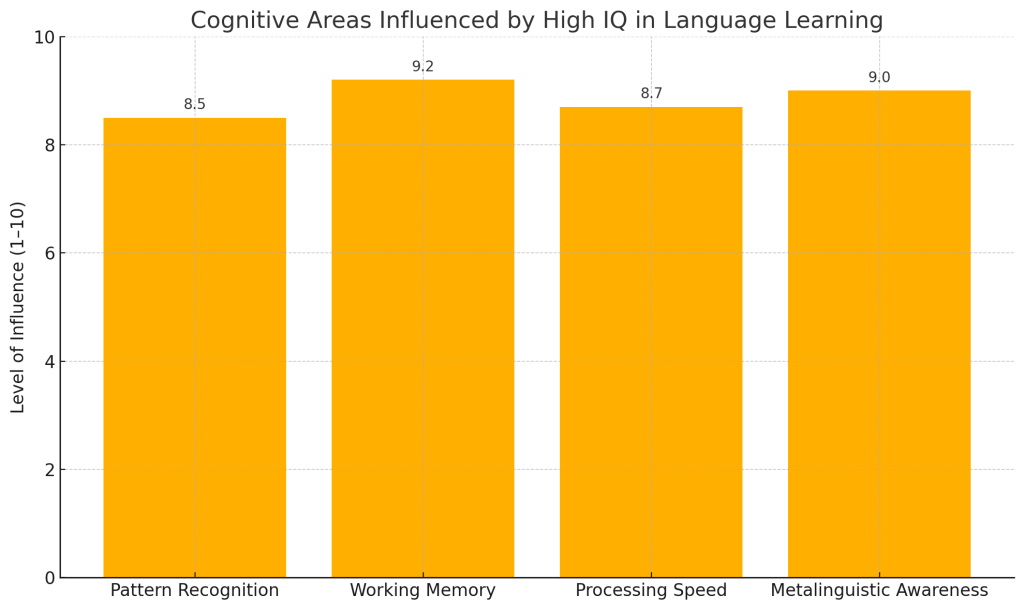

Figure 2 below provides a visual summary showing how high IQ influences key cognitive areas involved in language learning. Each bar represents the estimated strength of IQ’s influence in that domain on a scale from 1 to 10. Remember:

- Pattern Recognition: Helps identify grammar and structure.

- Working Memory: Supports holding and manipulating language input.

- Processing Speed: Aids quick comprehension and response.

- Metalinguistic Awareness: Enhances understanding of language as a system

Figure 3. Estimated Influence of IQ Across Language-Related Cognitive Domains

3. How Low IQ Interacts with Language Learning

These cognitive advantages for high-IQ learners, however, highlight a deeper concern: what happens when learners do not possess high IQ? Research shows that students with lower IQs may find it more difficult to infer grammar rules, retain complex sentence structures, or apply learned rules with consistency in productive skills like writing (Sparks, Patton, & Ganschow, 2012). For example, a student who struggles with working memory might be able to complete a gap-fill grammar task accurately when focused but fail to apply the same rule when writing a paragraph. This disconnect is not due to laziness or lack of motivation—it’s a cognitive bottleneck.

Learners with lower IQs may not simply be ‘slower’; their challenges often stem from genuine cognitive constraints that affect how they process, store, and retrieve language.

In grammar acquisition, for instance, low-IQ learners may struggle with rule abstraction and pattern generalisation. Hulstijn (2015) suggests that such learners often benefit more from implicit instruction and exposure than from formal grammar explanations. Rather than asking them to deduce when to use the past perfect, for example, it’s more effective to flood their input with natural, meaningful examples of that structures – preferably through listening and interaction. Routines are particularly effective as well as highly patterned texts such as narrow listening and narrow reading.

Writing is another area where difficulties become more visible. Studies such as Sparks et al. (2012) show that low-IQ learners often display persistent challenges with syntactic accuracy, organisation, and lexical variety. A practical classroom example: a learner may be able to write “I go school every day” with confidence but fail to incorporate a new structure like “I’ve been going to school since January” without significant, repeated modelling.

Importantly, success is still possible—just on different terms. Long-term studies (e.g., Ganschow & Sparks, 1995) demonstrate that with repetition, scaffolding, and high-frequency exposure, low-IQ learners can achieve communicative competence. To help such learners, teachers can draw on strategies from Ellis (2005) and VanPatten (2002). For instance, instead of lengthy explanations of grammar rules, input-based approaches such as ‘input flood‘ (where learners are exposed to many examples of a structure) or ‘input enhancement‘ (highlighting target forms in reading or emphasizing them vocally in listening activities) can offer repeated, low-stress exposure.

Careful and thorough modelling through Sentence builders, lots of repeated processing, masses of throughtfully scaffolded retrieval practice, sufficient planning time before challenging tasks, intensive vocabulary teaching before tacking challenging texts, etc, also allow learners with limited processing speed to build automaticity over time. Writing tasks should be scaffolded with models, checklists, and sentence stems. A lower-IQ learner, for instance, may benefit from a writing frame that structures a paragraph: “First, I usually ___. Then, I like to ___. Finally, I ___.” Over time, these supports can be gradually removed as learners gain confidence and fluency.

What often matters most is not cognitive firepower but consistency, clarity, and emotional support from teachers. Recasting errors positively, chunking input, and gradually increasing task complexity are all essential strategies.

This is not about lowering expectations—it’s about adjusting the path. When instruction meets learners where they are, the journey becomes not just possible, but rewarding.

4. Mixed-Ability Classrooms: Pros and Cons of Grouping Learners Across the IQ Spectrum

Bringing together learners with widely differing IQ levels into a single language classroom is increasingly common, especially in inclusive education settings. This approach carries both potential benefits and significant challenges.

On the positive side, mixed-ability classrooms can foster peer learning and collaborative growth. Vygotsky’s (1978) concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) supports the idea that less advanced learners can benefit from interacting with more capable peers. High-IQ students often provide linguistic models, expose others to more sophisticated structures, and, in doing so, reinforce their own knowledge through teaching. Meanwhile, learners with lower IQ may benefit from simplified explanations and indirect scaffolding via peer talk.

However, research also highlights several limitations. Sweller’s (1988) cognitive load theory warns that low-IQ learners may experience overload when required to process input at the level of their more advanced peers, especially without sufficient differentiation. This can lead to frustration, disengagement, or fossilisation of errors. High-IQ learners, on the other hand, may feel held back or insufficiently challenged, particularly if tasks are overly simplified to accommodate others. Additionally, the classroom dynamics can suffer when learners perceive inequity—either in terms of pace or teacher attention. Research by Kulik and Kulik (1992) on ability grouping suggests that high-achieving students in mixed-ability settings may show diminished gains compared to those in homogeneous groups. Simultaneously, low-IQ learners may develop learned helplessness if they are frequently exposed to performance gaps that feel insurmountable (Dweck, 2006). Teachers might inadvertently lower expectations for some students, which can reduce both challenge and opportunity for growth across the class.

The key to successful mixed-ability teaching lies in targeted differentiation, flexible grouping, and scaffolded instruction. As Tomlinson (2014) argues, differentiation isn’t about creating separate curricula but about adjusting inputs, tasks, and supports so that each learner can access the same core content meaningfully. In practice, this might mean giving high-IQ learners more open-ended writing prompts or inductive grammar puzzles, while offering lower-IQ students structured sentence frames and more guided input tasks. When planned thoughtfully, mixed-ability classes can be inclusive, empowering, and pedagogically sound.

However, the promise of differentiation in mixed-ability classrooms often falls short in real-world language teaching contexts. Several studies have raised doubts about the practical effectiveness of differentiation, particularly in language education. For example, Westwood (2013) and Hattie (2009) argue that while differentiation sounds ideal in theory, it is difficult to implement with sufficient depth and consistency in classrooms with large student numbers, time constraints, and curriculum demands. Language teachers, in particular, report struggling to create tiered tasks that are cognitively appropriate, linguistically accessible, and pedagogically sound for all learners simultaneously (Connor, Morrison, & Katch, 2004).

Furthermore, research from the OECD (2012) suggests that attempts at differentiation often result in ‘teaching to the middle’—whereby high-achieving learners are insufficiently stretched and lower-achieving learners remain unsupported. In language classrooms, where progression is cumulative and requires automatization through repetition, the attempt to customise content for every ability level can dilute the intensity of exposure and reduce opportunities for recycling key structures—an essential condition for acquisition (VanPatten, 2002). In practice, this means that the intended support mechanisms may not reach the learners who need them most, and that instruction can become fragmented and less impactful overall. Even when differentiation is attempted, it is often superficial—focused more on varying task difficulty than on tailoring learning trajectories in a way that is both linguistically meaningful and cognitively appropriate. Tatzl (2013) found that teachers frequently rely on the same materials for all learners, with only minor adjustments, due to time, training, and resource constraints. This often leaves both ends of the learner spectrum underserved.

Moreover, differentiation can inadvertently create a “labelling effect,” reinforcing perceptions of fixed ability among learners (Boaler, 2013). When students are consistently grouped or given tasks based on perceived aptitude, it can shape their self-concept and influence motivation. For language learners, where confidence and willingness to communicate are critical, this can have lasting implications.

Ultimately, while differentiation remains a well-intentioned strategy, the evidence suggests that without sustained support, ongoing professional development, and appropriate structural conditions – which schools more than often do not get! – it is often more aspirational than effective in the reality of language classrooms.

Based on my 28 years of teaching languages in a wide range of contexts—from top-performing schools to mixed-ability state settings—I can confidently say that differentiation, while noble in intent, often collapses under the weight of classroom reality. In practice, differentiation is frequently superficial and reactive rather than embedded and strategic. It tends to favour the middle ability range, leaving the most and least cognitively able learners underserved. Teachers are often not given the training, planning time, or resources to differentiate meaningfully, and the result is either watered-down content or overly complex tasks repackaged with minor tweaks. That said, in my experience, mixed-ability teaching can work reasonably well when the spread of ability in the classroom is not too wide. When learners fall within a manageable cognitive range, differentiation becomes more feasible, peer support is more balanced, and instructional planning remains realistic. It’s when the gap becomes extreme that the cracks begin to show—making approaches like EPI, which naturally embed scaffolding for all, a far more sustainable solution.

All considered, though, I firmly believe that what truly makes a difference is not splitting learners into tiers, but giving everyone access to high-quality input, extensive modelling, and tasks that build up from controlled to freer practice over time—principles that approaches like EPI embody far more effectively than ad-hoc differentiation ever could.

5. Concluding remarks

This article has explored the complex interplay between IQ and second language acquisition. The evidence suggests that high IQ can support language learning in several key areas—pattern recognition, working memory, processing speed, and metalinguistic awareness—often leading to quicker uptake of grammar and vocabulary, better processing of input, and more efficient use of explicit instruction. However, IQ is not destiny. Learners with lower IQ may struggle more with rule abstraction and memory-heavy tasks, particularly in grammar and writing, but they can still succeed through well-designed instruction, repetition, and emotional support.

One framework that accommodates both ends of the cognitive spectrum is Extensive Processing Instruction (EPI). Grounded in ISLA principles, EPI provides structured input, controlled output, and scaffolded repetition. It plays to the strengths of high-IQ learners through inductive reasoning and pattern recycling, while supporting lower-IQ learners with sentence builders, input flood, and low-stakes, repeated practice. Rather than dumbing down the content, EPI simplifies the processing—making language acquisition accessible, meaningful, and rewarding for everyone.

High IQ can provide significant cognitive advantages in language learning, particularly in areas like pattern recognition, working memory, processing speed, and metalinguistic awareness. However, intelligence is not the sole determinant of language learning success. Motivation, exposure, resilience, and cultural immersion are equally, if not more, influential in many contexts. For learners with lower IQs, adaptive instruction and supportive learning environments play a critical role in promoting success.

References

- Boaler, J. (2013). Ability and Mathematics: The Mindset Revolution That Is Reshaping Education. Forum, 55(1), 143–152.

- Connor, C. M., Morrison, F. J., & Katch, L. E. (2004). Beyond the Reading Wars: Exploring the Effect of Child-Instruction Interactions on Growth in Early Reading. Scientific Studies of Reading, 8(4), 305–336.

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random House.

- Ellis, N. C. (2002). Frequency effects in language processing: A review with implications for theories of implicit and explicit language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 24(2), 143–188.

- Ellis, R. (2005). Principles of instructed language learning. System, 33(2), 209–224.

- Ganschow, L., & Sparks, R. (1995). Effects of Direct Instruction in Spanish Phonology on the Native-Language Skills and Foreign-Language Aptitude of At-Risk Foreign-Language Learners. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 28(2), 107–120.

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. Routledge.

- Hulstijn, J. H. (2015). Language proficiency in native and non-native speakers: Theory and research. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Kulik, C.-L. C., & Kulik, J. A. (1992). Meta-analytic findings on grouping programs. Gifted Child Quarterly, 36(2), 73–77.

- OECD (2012). Equity and Quality in Education: Supporting Disadvantaged Students and Schools. OECD Publishing.

- Sparks, R., Patton, J., & Ganschow, L. (2012). Profiles of More and Less Successful L2 Learners: A Cluster Analysis Study. Learning and Individual Differences, 22(4), 463–472.

- Swain, M. (2000). The output hypothesis and beyond: Mediating acquisition through collaborative dialogue. Sociocultural theory and second language learning, 97–114.

- Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285.

- Tatzl, D. (2013). Engineering students’ beliefs about language learning and their proficiency in English for specific purposes. English for Specific Purposes, 32(1), 1–11.

- Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners (2nd ed.). ASCD.

- VanPatten, B. (2002). Processing instruction: An update. Language Learning, 52(4), 755–803.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press.

- Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. Psychology of Learning and Motivation.

- Bialystok, E., & Ryan, E. B. (1985). A metacognitive framework for the development of first and second language skills. Applied Psycholinguistics.

- Carroll, J. B. (1990). Cognitive abilities in foreign language aptitude: Then and now. Language Aptitude Research.

- Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and Motivation in Second-Language Learning. Newbury House Publishers.

- Gombert, J. E. (1992). Metalinguistic Development. University of Chicago Press.

- Kail, R., & Salthouse, T. A. (1994). Processing speed as a mental capacity. Acta Psychologica.

- Miyake, A., & Friedman, N. P. (1998). Individual differences in second language proficiency: Working memory as language aptitude. Psychological Science.

- Rostami, M., Rezaabadi, O. T., & Gholami, J. (2013). On the relationship between intelligence and English language learning. Journal of Language, Culture, and Translation.

- Sheppard, L. D., & Vernon, P. A. (2008). Intelligence and speed of information-processing: A review of 50 years of research. Personality and Individual Differences.

- Skehan, P. (1998). A Cognitive Approach to Language Learning. Oxford University Press.

If you do want to find out more on the topic and on my approach to instructed second language acquisition, do get hold of my books (here). I would especially recommend the following tomes, co-authored with Steve Smiths: ‘Breaking the sound barrier: teaching language learners how to listen, ‘The language teacher toolkit’ and ‘Memory: what every language learner should know’.

You must be logged in to post a comment.