Introduction

When it comes to assessing grammar in a Modern Foreign Language (MFL) classroom, especially with beginner to intermediate learners, it should be much more than just ticking boxes. Grammar learning is messy, gradual, and happens best through real use—not through artificial drills. Good grammar assessments need to reflect how languages are actually acquired. After all, in real communication, we use grammar to tell stories, explain ideas, argue our points—not just to get full marks on a worksheet. In this article, drawing on some of the most trusted research in second language acquisition (SLA) and cognitive psychology, we’ll walk through 10 key principles that can help make grammar assessment in MFL classrooms more meaningful, motivating, and effective.

1. Focus on Meaningful Use

Grammar should never be an end in itself. It’s a tool to communicate. So, assessments should check if students can use grammar meaningfully. For example, instead of giving students random sentences to correct, why not ask them to write a blog post about their weekend, naturally applying the passé composé (Samedi, je suis allé au cinéma). Assessments should make grammar “task-essential,” meaning students can’t succeed without using it. In other words, the task must naturally require the target structure for successful completion. For instance, a beginner Spanish activity might ask students to describe their family members using simple adjectives (Mi madre es simpática; Mi padre es alto), thereby assessing adjective-noun agreement authentically. When tasks demand real application of grammar for communicative purposes, learners are more likely to process the form deeply and retain it.

2. Prioritise Core Structures and 3. Put mastery before breadth

Let’s be realistic: some grammar structures are way more useful than others. Assessment should zoom in on high-frequency, high-utility structures—the ones students will actually need in everyday life. Think present tense -er verbs, basic negatives (ne…pas), and simple prepositions. Nation (2001) argues that focusing on what students use most pays off much more than chasing rarer forms. Focus on a handful of non-negotiables every year, ensuring that you don’t lose sight of them and keep assessing them until you believe they have become fluent in their deployment. Do bear in mind that the acquisition of a grammar structure may take months or even years; hence, assessing the acquisition of fewer foundational structures several times a year is more likely to pay higher dividends then assessing a multitude of structures (a la NCELP/LDP). The former approach will ensure that mastery of key grammar structures is attained and retained in the long term, so that you don’t have to keep re-teaching them ; the latter will obtain short-term gains that are likely to fade away in the space of a few weeks.

4. Assess Receptive and Productive Knowledge

Grammar competence usually shows up first in receptive skills like listening and reading before becoming visible in speaking and writing. That’s why it’s so important to assess both. For example, you could combine a listening task where students spot tense errors with a writing task where they narrate a past event. Larsen-Freeman (2015) and Hulstijn (2001) highlight that this sequence—recognising first, producing later—is how grammar naturally develops. Learners often notice forms months before they can reliably produce them. By embedding both recognition and production in assessments, we mirror this developmental path and avoid penalising students unfairly for being in the early phases of acquisition. Sadly, in many MFL classrooms this very important point is flouted and grammar assessments tend to be exclusively productive in nature.

5. Reward Emerging Accuracy and Scaffold Risk-Taking

Language learning is a messy, step-by-step process. Full accuracy doesn’t happen overnight! That’s why assessments should reward partial success. If a student writes je parl avec mon ami, we should acknowledge the correct stem, even if the ending is missing. Giving credit where it’s due builds confidence and encourages students to take risks with new structures, which is crucial for growth (Pienemann, 1998; Ellis, 2008; Dörnyei, 2005). Risk-taking is essential because learners often avoid using newly learned forms unless they feel safe experimenting. A reward system that notices approximate success gives learners emotional permission to stretch themselves beyond their current comfort zone.

6. Vary Modes of Assessment

Real language use involves all four skills—listening, speaking, reading, and writing. So, grammar assessment should do the same, but always keep the same structure in focus. For example, all tasks could target the passé composé:

This varied approach also keeps students engaged and gives them different ways to show what they know (Dörnyei, 2009; Purpura, 2004). Exposure across skills also strengthens grammatical automaticity and reduces the reliance on slow, conscious monitoring.

7.Provide Immediate, Formative Feedback where possible (e.g. when preparing for high-stake examinations)

Students benefit massively from getting feedback while they’re still working things out. During mock speaking exams, for instance, teachers could gently recast errors: il allé au parc? → il est allé au parc? This kind of immediate feedback supports restructuring and stops mistakes from fossilising (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Lyster & Ranta, 1997). It’s important that feedback be timely, encouraging, and specific, drawing learners’ attention not only to what went wrong but to how the correct form feels and sounds in authentic usage.

8.Track Progress Over Time

Grammar learning doesn’t follow a straight line. It zigzags, loops, and sometimes even goes backwards before moving forward again. One-off tests can’t tell the full story. Instead, keep “Grammar Growth Trackers” where students log milestones—like the first time they correctly used a tricky structure. This aligns better with the staged, dynamic way grammar develops (Pienemann, 1998; Ellis, 2008). Using trackers also empowers learners to take ownership of their grammatical progress, making growth visible and therefore more motivating.

This links up with what we said above about prioritising a set of non-negotiable structures every year to assess several times at spaced intervals in order to ensure that the students become fluent with them.

9. Ensure Validity of Scoring in Mixed-Skill Tasks

In translation tasks, it’s common for students to make vocabulary and grammar mistakes in the same sentence. To be fair, assessments should separate the two: mark grammar independently of vocabulary. If a student mistranslates a noun but uses the correct verb tense, they should still earn grammar marks. Clear rubrics are key here (Alderson, 2005; Purpura, 2004). Without such clarity, learners risk being penalised twice for a single idea error, leading to skewed assessment outcomes that demoralise rather than diagnose accurately.

10. Avoid Over-Reliance on Guessable Formats

Tasks like grammaticality judgment activities (“Is this sentence correct or incorrect?”) can seem quick and easy, but they come with a big downside: students have a 50/50 chance of guessing the right answer! That’s not a true test of knowledge. If you do use grammaticality judgment tasks as assessment tools, you can enhance their validity by asking the students to justify their answers and correct the mistakes in the target sentences where applicable.

To really assess what students know, it’s always good practice to mix comprehension tasks with production tasks that require active use (Alderson, 2005; Hulstijn, 2001). Production tasks (like rewriting or filling blanks contextually) force deeper retrieval and construction processes, giving a much clearer window into learners’ true grammatical competence.

Conclusion

Moving towards smarter, research-informed grammar assessment means making a few key shifts: focusing on meaning over isolated accuracy, prioritising frequent structures, rewarding effort and risk-taking, and tracking growth over time. It also means creating tasks that reflect real communication—and avoiding shortcuts that let students succeed through guessing. With these principles in mind, grammar assessment can become a powerful tool not just for measuring learning, but for building it.

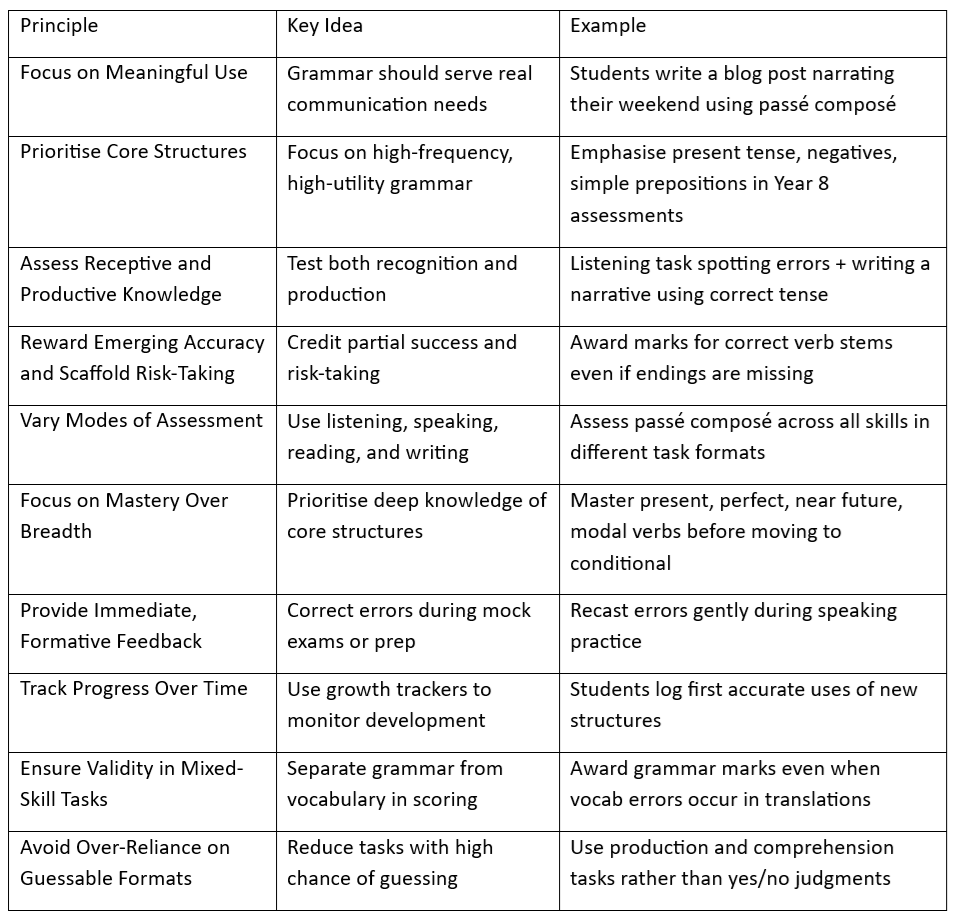

Summary Table: Key Principles for Grammar Assessment

References

Alderson, J. C. (2005). Assessing Reading. Cambridge University Press.

Smith, S. & Conti, G. (2020). Memory: What Every Language Teacher Should Know. Independently Published.

Doughty, C., & Williams, J. (1998). Focus on Form in Classroom Second Language Acquisition. Cambridge University Press.

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The Psychology of the Language Learner: Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition. Routledge.

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 Motivational Self System. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self (pp. 9–42). Multilingual Matters.

Ellis, R. (2005). Measuring Implicit and Explicit Knowledge of a Second Language: A Psychometric Study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 27(2), 141–172.

Ellis, R. (2008). The Study of Second Language Acquisition (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112.

Hulstijn, J. H. (2001). Intentional and Incidental Second Language Vocabulary Learning: A Reappraisal of Elaboration, Rehearsal and Automaticity. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and Second Language Instruction (pp. 258–286). Cambridge University Press.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2015). Research into Practice: Grammar Learning and Teaching. Language Teaching, 48(2), 263–280.

Lyster, R., & Ranta, L. (1997). Corrective Feedback and Learner Uptake: Negotiation of Form in Communicative Classrooms. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19(1), 37–66.

Marsden, E., & Kasprowicz, R. (2017). Foreign Language Practice Activities for Beginner Learners: A Comparison of Three Types of Activity. The Language Learning Journal, 45(1), 20–40.

Nation, I. S. P. (2001). Learning Vocabulary in Another Language. Cambridge University Press

You must be logged in to post a comment.