Introduction

In this article, I aim to provide practical, research-informed guidance on how written corrective feedback (WCF) in second language (L2) classrooms can be implemented more effectively and meaningfully—particularly under real-world teaching constraints.

This is a topic I’ve been personally invested in for over two decades. More than 20 years ago, I conducted my PhD research on the role of metacognitive strategies in error correction and the impact of self-monitoring on L2 writing.

My review of the specialised literature during the first year of my study made it all too clear to me that WCF is a far more complex issue than it appears on the surface. It is much more than simply marking errors, it must empower learners to become active, intentional, self-monitoring agents. Easier said than done!, you may think to yourself as you read this. Can’t blame you. Yet, the success of WCF is all about student intentionality.

My PhD study also taught me a very hard lesson: doing WCF well requires a lot of time, the one commodity busy teachers in secondary schools around the world are very poor in! It also requires training that many teachers may not be able to access.

Given these practical realities, one cannot expect that language educators implement every ideal practice suggested by research! Hence, the guidelines below are intended as a roadmap for gradual improvement rather than as a strict checklist or a criticism of current practice.

Here are twelve common shortcomings of WCF practice, many of which I have been guilty of myself.

11 common pitfalls evidenced by research into WCF

1. Reduced Learner Intentionality

When learners receive a barrage of corrections without clear guidance on which errors are most significant, they tend to become passive recipients of feedback. Swain (1995) argues that for effective error correction, learners must actively notice the gap between their interlanguage and the target language. Intentional engagement—where students compare their output with the correct form—builds metacognitive skills and reinforces self-correction. Ellis (2006) confirms that intentional self-correction promotes deeper processing and helps prevent fossilisation (Ferris, 2018).

Research by Lalande, Ferris, and Conti (2004) demonstrates that explicit instruction in self-monitoring strategies significantly improves learners’ error awareness and independence. Multiple classroom studies (e.g., Hyland & Hyland, 2006) have reported that students often feel overwhelmed by unstructured corrections, reducing their willingness to engage in self-initiated revision.

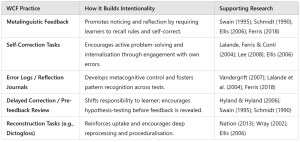

Figure 1 – WCF practices which foste rintentionality according to research

2. Insufficient Promotion of Self-Monitoring Strategies

Feedback that merely supplies the correct answer without prompting reflective comparison limits the development of metacognitive skills. Swain (1995) emphasizes that self-monitoring is critical; learners must be encouraged to actively compare their output with target forms. Studies by Vandergrift (2007) and Lalande, Ferris, and Conti (2004) indicate that learners trained in self-monitoring strategies become better at detecting and addressing recurring errors independently.

Empirical classroom research (Hyland & Hyland, 2006) documents that many teachers continue to provide corrections without engaging students in the reflective process. This omission prevents the development of independent editing skills, underscoring the need for explicit self-monitoring prompts in corrective feedback.

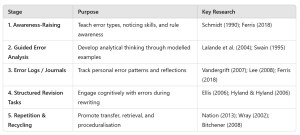

Figure 2 – Self-Monitoring Strategy Training in WCF

3. Overcorrection Leading to Cognitive Overload

Correcting every minor error can overwhelm learners’ limited working memory. Research consistently shows that correcting too many errors at once can lead to cognitive overload and reduced learning gains (Miller, 1965; Baddeley, 2003). Learners, especially those at lower proficiency levels, often struggle to process an excessive amount of feedback simultaneously. Bitchener (2008) and Ferris (2018) argue that focusing on high-priority or recurring errors—such as those that impede communication or reflect underlying gaps in knowledge—is more beneficial than marking every minor slip. Ellis (2006) supports this by advocating for focused feedback, which has been shown to result in greater long-term accuracy than unfocused correction. In short, quality over quantity is essential: teachers must strategically choose which errors to address in order to support deeper processing and reduce learner frustration.

Hyland and Hyland (2006) found that many teachers tend to mark nearly every error without filtering for significance. This unselective approach, documented in studies such as Bitchener (2008), increases cognitive demands and hinders the internalisation of corrections.

4. Differentiating Error Sources: Treating Errors Based on Their Origin

Errors in L2 writing often stem from different underlying issues. Some mistakes occur due to a lack of correct declarative knowledge—for instance, when a learner has not fully internalised an explicit grammar rule (Ellis, 2006). Other errors arise from insufficient procedural knowledge, where the learner knows the rule in theory but cannot consistently apply it automatically under real-time conditions (Swain, 1995; Norris & Ortega, 2000). Research indicates that these error types require different remedial approaches: explicit instruction and explanation are most effective for declarative knowledge gaps, while extensive practice and recycling promote the proceduralisation of rules. This differentiation is crucial; by tailoring feedback to the source of the error, teachers can provide more targeted and effective corrective strategies, as supported by Lalande, Ferris, and Conti (2004).

5. Lack of Clarity and Intelligibility

Ambiguous correction symbols or overly technical language in feedback can leave students confused about what is wrong and why. Ferris (2018) notes that clear, accessible feedback is essential for helping learners understand the nature of their errors, while Lee (2008) found that when corrections are explained in straightforward terms, students are more likely to grasp the intended meaning and apply the changes successfully.

Research by Hyland and Hyland (2006) consistently shows that many teachers use unclear or inconsistent symbols and comments, which undermines the corrective process and reduces the likelihood that learners will internalise the correct forms.

6. Delayed Feedback

When corrections are provided long after the writing task, the link between the error and its correction can weaken considerably. Long (2015) emphasizes that timely feedback is critical so that learners can immediately rehearse the correct forms while the context is still fresh in memory. Bitchener and Knipe (2008) support this view by demonstrating that prompt feedback is significantly more effective for error correction than delayed responses.

Classroom studies (Hyland & Hyland, 2006) indicate that many teachers delay feedback due to workload constraints or scheduling issues, thereby diminishing the impact of corrective information.

7. Inconsistency in Correction Methods

Using varied correction styles within or across texts can confuse students about which errors to address. Lyster and Ranta (1997) recommend that consistent correction techniques help establish stable error patterns, making it easier for learners to recognise and correct recurring mistakes. Inconsistent feedback dilutes the corrective message and leaves students uncertain about the relative importance of different errors.

Research by Bitchener (2008) documents that many teachers employ multiple correction systems simultaneously, and classroom observations (Hyland & Hyland, 2006) indicate that such inconsistency is a common issue that hinders students’ ability to develop a systematic approach to self-correction.

8. Missed Opportunities for Reprocessing and Revision

Without structured revision tasks or follow-up activities, students do not have sufficient opportunities to reprocess and internalise corrective feedback. Ferris (2018) and Swain (1995) note that learning from corrective feedback is not an instantaneous “aha” moment but a gradual process that benefits from deliberate re-engagement with the material. Follow-up revision tasks—such as re-writing exercises or peer review sessions—allow students to revisit corrections and strengthen the connection between error and resolution.

Studies by Lee (2008) consistently find that many teachers neglect to incorporate systematic revision activities after providing feedback, limiting the potential for long-term improvement.

9. Failure to Tailor Feedback to Individual Needs

Uniform feedback that does not account for differences in proficiency or individual learning strategies is less effective. Ellis (2006) has shown that customised feedback—addressed to a learner’s specific error patterns—supports better self-regulated learning and targeted improvement. Tailored feedback ensures that students receive the most relevant information for their own language development, thereby supporting more effective error correction.

Surveys and interviews by Norris and Ortega (2000) reveal that many teachers still adopt a one-size-fits-all approach, ignoring individual differences. This common shortcoming is linked to lower overall improvement rates among diverse learners.

10. Neglecting the Prevention of Fossilisation

When feedback is not clear, timely, or consistently managed, persistent errors can become fossilised in the learner’s interlanguage. Selinker’s (1972) seminal work, along with subsequent studies (Norris & Ortega, 2000), demonstrates that without strategic and ongoing corrective feedback, errors tend to become entrenched and resistant to change. Fossilised errors hinder long-term language development and are particularly difficult to eradicate once established.

Multiple studies (Ferris, 2018; Swain, 1995) document that many teachers fail to provide the continuous, focused feedback necessary to prevent fossilisation, underscoring the need for systematic, sustained error correction strategies.

11. Overemphasis on Remediation Instead of Prevention

A common pitfall in L2 writing instruction is focusing too much on remedial correction—reacting to errors after they occur—instead of preventing errors through careful instructional design and curriculum planning. While remedial feedback is necessary, a heavy reliance on it can result in reactive teaching that fails to address the root causes of errors. Research by VanPatten (2004) and Ellis (2006) suggests that integrating prevention strategies—such as designing scaffolded tasks, providing ample practice with target forms, and ensuring consistent recycling of language elements—can significantly reduce the overall error incidence. Norris and Ortega (2000) have shown that a curriculum focused on prevention leads to fewer errors and a smoother learning process. By shifting the focus from remediation to prevention, teachers create a learning environment where correct language forms are reinforced before errors become ingrained, thereby reducing the need for later correction and supporting long-term language development.

Implications for L2 pedagogy: I.M.P.A.C.T.E.D.

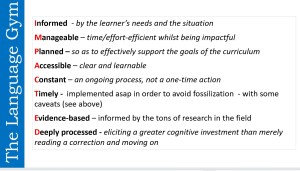

I.M.P.A.C.T.E.D. (see figure 1 below) is an acronym I have come up with which encapsules the main recommendations by researchers.

Figure 2 – the IMPACTED framework for WCF

Informed feedback must respond to the learner’s needs and the specific context of the task. Research underscores the importance of tailoring feedback to learner proficiency and developmental readiness (Ellis, 2006; Ferris, 2018). Generic correction is rarely as effective as feedback based on diagnostic insight into the learner’s interlanguage and common error patterns (Lalande, Ferris & Conti, 2004).

Manageable feedback recognises the reality of teacher workload and the cognitive limits of learners. Overloading either party compromises learning. Miller’s (1965) classic findings on working memory capacity (7 ± 2 items) and Baddeley’s (2003) work on cognitive load stress the need for focus. Bitchener (2008) also highlights that teachers must be selective, correcting only what is most useful for long-term development.

Planned feedback aligns with long-term instructional goals rather than being merely reactive. VanPatten (2004) and Swain (1995) stress the need for integrating feedback within structured learning cycles. When feedback is anticipated and followed up by recycling and revision tasks, learners process it more deeply (Ferris, 2018).

Accessible feedback should be clear and learnable. Studies by Lee (2008) and Hyland & Hyland (2006) demonstrate that learners benefit most from feedback that uses student-friendly language and models corrections clearly. Ambiguity reduces the effectiveness of even well-intended feedback.

Constant feedback must be part of a continuous loop. Research supports the idea that revision and reprocessing are essential for internalisation (Swain, 1995; Ferris, 2018). Lalande, Ferris & Conti (2004) found that sustained engagement with feedback over time enhances self-monitoring and long-term gains.

Timely feedback helps prevent fossilisation of errors (Long, 2015; Bitchener & Knipe, 2008). When feedback is delivered while the task is still cognitively present, learners are more likely to reflect and revise meaningfully. Delayed correction often loses its pedagogical power.

Evidence-based feedback is grounded in a substantial body of SLA research. Focused feedback (Ellis, 2006), metalinguistic correction (Lyster & Ranta, 1997), and self-monitoring routines (Lalande, Ferris & Conti, 2004) have all been shown to support learner development. Using research-backed strategies ensures that feedback efforts are not wasted.

Deeply processed feedback demands active engagement. Wray (2002), Schmidt (1990), and Swain (1995) argue that noticing and reflection are prerequisites for acquisition. Simply reading corrections is not enough—learners must cognitively work through them, revise, and apply corrections in new contexts for lasting learning to occur.

Conclusion

Effective L2 written corrective feedback must do more than simply correct errors; it must foster intentional engagement that transforms feedback into an active learning process. When learners actively notice discrepancies between their writing and the target language, they build the metacognitive skills necessary for self-monitoring and independent improvement. Clear, timely, and prioritised feedback—combined with structured revision tasks—reduces cognitive overload and helps ensure that corrections are gradually internalised, preventing error fossilisation (Ferris, 2018; Swain, 1995).

It is also important to recognise that teachers face significant time constraints and heavy workloads. Research by Lalande, Ferris, and Conti (2004) underscores that while promoting self-monitoring and strategic feedback is highly beneficial, not every ideal practice can be implemented in every classroom. Teachers should not feel guilty or as if they are being criticised for not doing everything perfectly—there is only so much that can be accomplished given practical realities. Instead, these guidelines offer a roadmap for gradual, intentional improvement in feedback practices, including an emphasis on preventing errors through proactive instructional design.

In essence, intentional engagement in the feedback process is the foundation of long-term success. As students learn to understand and work through their mistakes with clear, structured, and manageable feedback, they develop greater autonomy and become more effective communicators. This holistic approach not only improves written proficiency but also contributes to a sustainable, self-regulated language learning process.

References

• Baddeley, A. (2003). Working memory: Looking back and looking forward. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 4(10), 829–839.

• Bitchener, J. (2008). Written corrective feedback in second language acquisition and writing. Language Teaching, 41(2), 159–182.

• Ellis, R. (2006). The Study of Second Language Acquisition. Oxford University Press.

• Ferris, D. R. (2018). Response to Student Writing: Implications for Second Language Learners. Routledge.

• Hyland, F., & Hyland, K. (2006). Feedback in second language writing: Contexts and issues. Cambridge University Press.

• Kormos, J., & Csizér, K. (2014). The interaction of motivation, self-regulatory strategies, and language proficiency. Language Learning, 64(2), 285–310.

• Lalande, D., Ferris, D. R., & Conti, G. (2004). Promoting self-monitoring in second language writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13(2), 123–139.

• Lee, I. (2008). Effects of corrective feedback on second language writing development. Journal of Second Language Writing, 17(2), 102–118.

• Lyster, R., & Ranta, L. (1997). Corrective feedback and learner uptake: Negotiation of form in communicative classrooms. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19(1), 37–66.

• Long, M. H. (2015). How Languages are Learned. Oxford University Press.

• Miller, G. A. (1965). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 72(2), 343–352.

• Norris, J. M., & Ortega, L. (2000). Effectiveness of L2 instruction: A research synthesis and quantitative meta-analysis. Language Learning, 50(3), 417–528.

• Schmidt, R. (1990). The role of consciousness in second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 11(2), 129–158.

• Selinker, L. (1972). Interlanguage. IRAL – International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 10(3–4), 209–232.

• Swain, M. (1995). Three functions of output in second language learning. In G. Cook & B. Seidlhofer (Eds.), Principle and Practice in Applied Linguistics (pp. 125–144). Oxford University Press.

• VanPatten, B. (2004). Processing instruction and grammar teaching: A case for explicit training. In M. H. Long (Ed.), Key Issues in Second Language Acquisition (pp. 157–176). Routledge.

• Vandergrift, L. (2007). Extensive listening practice: An experimental study. The Modern Language Journal, 91(4), 605–621.

You must be logged in to post a comment.