Introduction

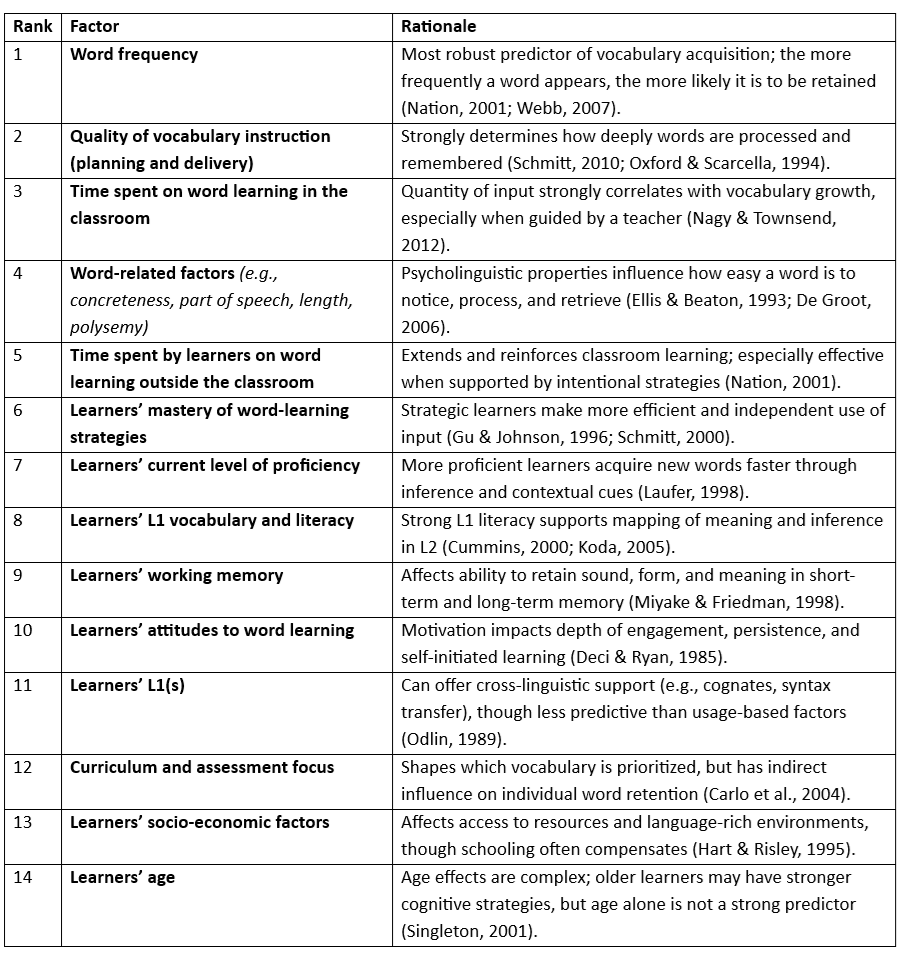

As I often reiterate in my posts, vocabulary acquisition is the lifeblood of successful second language learning. It underpins listening comprehension, reading fluency, expressive speaking, and even grammatical development. Yet, while it is clear that acquiring a large and usable lexicon is essential, it is less obvious which factors most powerfully drive vocabulary growth.

Over decades, research in second language acquisition (SLA), cognitive psychology, and educational linguistics has revealed that some variables matter far more than others. This article ranks fourteen such variables by their likely impact on L2 vocabulary learning, based on accumulated empirical evidence. Along the way, it seeks to offer teachers, curriculum designers, and language learners themselves a roadmap to more efficient, strategic word acquisition.

1. Word Frequency

As discussed extensively in a previous post, word frequency is consistently identified as the most powerful predictor of successful vocabulary acquisition. Nation (2001) and Webb (2007) demonstrated that words occurring frequently in input are learned faster and remembered longer than low-frequency words, even when difficulty is controlled. Learners generally need at least 8–12 meaningful encounters to establish a stable mental representation of a word, and around 20–30 spaced repetitions to embed it into long-term memory.

However, not all exposures are equally useful: the diversity of contexts matters. Seeing se débrouiller (to cope, manage) in various settings like Il s’est bien débrouillé au travail, Je dois me débrouiller seul, and Comment te débrouilles-tu ? helps learners build rich semantic networks. Similarly, a word like chômage (unemployment) is better consolidated when used across structures like le taux de chômage, être en situation de chômage, and lutter contre le chômage.

Empirical studies show that with fewer than six spaced encounters, learners tend to remember fewer than 30% of new words after a week (Webb, 2007), whereas with 10 or more spaced encounters, recall rises above 80%. Frequency in input remains therefore a non-negotiable driver of vocabulary learning.

2. Quality of Vocabulary Instruction

Exposure alone is insufficient. The quality of vocabulary instruction dramatically modulates how efficiently and deeply words are acquired. Schmitt (2010) identified that explicit phonological modelling, semantic explanation, morphological decomposition, and repeated retrieval all significantly boost vocabulary retention compared to simple exposure.

Barcroft (2004) found that learners exposed to multimodal presentation — image, gesture, spelling, pronunciation, and sentence use — recalled 34% more words after two weeks than learners taught using isolated translation.

Meanwhile, Karpicke and Roediger (2008) demonstrated that retrieval practice — the act of recalling a word actively — produced 150% better long-term retention than re-reading or re-exposing learners to the word passively.

In practical terms, presenting épargner (to save money) by showing a photo of someone saving coins, miming the action, writing the word, pronouncing it carefully, and embedding it in J’épargne chaque mois pour mes vacances allows multiple memory routes to be built simultaneously, strengthening the trace exponentially.

Table 1 – Top 5 Effective Practices for Vocabulary Instruction

| Practice | Description | Key Research Support |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-teaching Vocabulary | Introducing and explaining key vocabulary before exposing learners to complex input tasks (e.g., texts, videos) | Nation (2001), Graves (2006) |

| Multimodal Presentation | Engaging visual, oral, physical (gestures) and textual channels to teach new words | Paivio (1991), Mayer (2001) |

| Retrieval Practice | Encouraging effortful recall through quizzes, low-stakes tests, gapfills, and oral production | Kang (2016), Bahrick (1979) |

| Rich and Varied Contexts | Recycling words in multiple genres, syntactic frames, and communicative tasks | Webb (2007), Schmitt (2010) |

| Spaced Repetition | Revisiting vocabulary over expanding intervals (e.g., 1 day, 3 days, 7 days, 14 days) | Cepeda et al. (2006), Nation (2001) |

3. Time Spent on Word Learning in the Classroom

A major body of research links time on vocabulary learning with larger vocabulary gains — but only when the time is cognitively engaged (Nagy & Townsend, 2012).

Spending as little as 10 additional minutes per session on structured, meaningful vocabulary activities can lead to 20–40% greater acquisition rates across a semester (Graves et al., 2011).

However, Pashler et al. (2007) and others stress that distributed retrieval is essential: learners must recall and use words actively at spaced intervals, not merely re-read them.

Whiteboard quizzes, retrieval flashcards, oral sentence building races, and quickfire memory games are among the classroom strategies that most efficiently drive vocabulary retention. Research indicates that when vocabulary practice involves active, varied retrieval and manipulation, retention rates can triple compared to passive exposure (Webb, 2007).

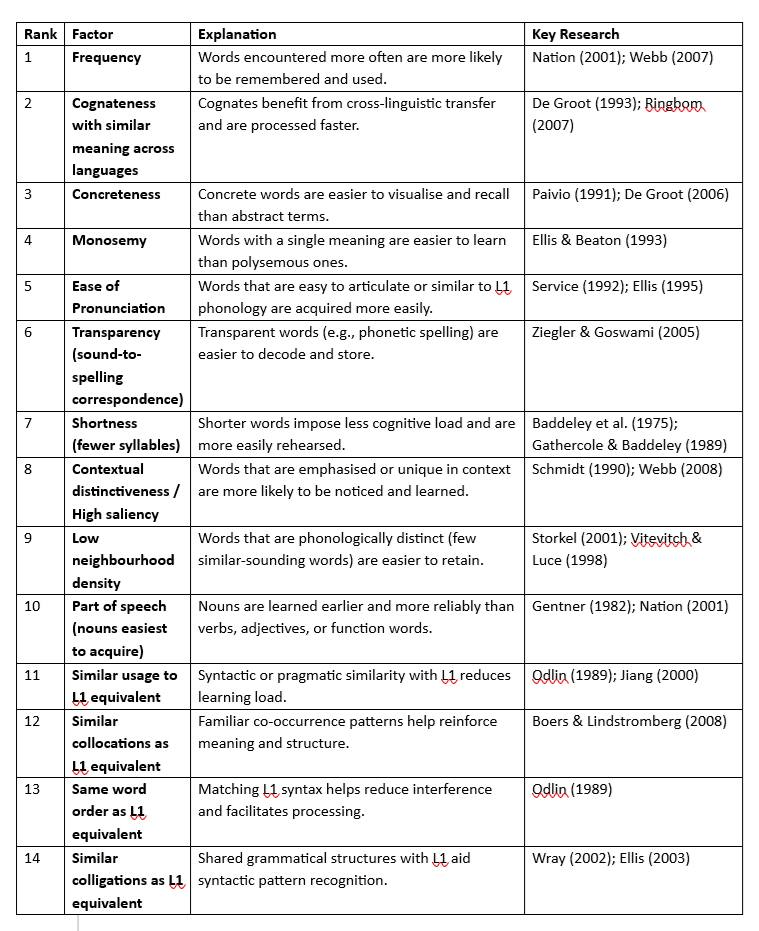

4. Word-Related Factors

Not all words are equally difficult to learn. Properties like concreteness, part of speech, morphological transparency, and polysemy make substantial differences.

Paivio’s (1991) dual-coding theory found that concrete words like bousculer (to jostle) or gronder (to scold) — easily visualised actions — are remembered more easily than abstract verbs like ressentir (to feel) or soutenir (to sustain/support emotionally).

Similarly, morphologically transparent words (prévoir — to foresee) are acquired faster than opaque forms like se méfier (to distrust), where no immediate morphology clues are available.

Polysemous words — like livre (book/pound) — add complexity: learners must develop multiple semantic traces to master full meaning usage, which research shows may require 20% more exposures on average (Crossley et al., 2009).

Table 2 – Word-related factors affective learnability

5. Time Spent by Learners Outside the Classroom

Outside engagement is critical. Nation (2001) and Webb (2007) found that learners who studied independently for even 10–15 minutes per day using structured activities gained 25–30% more vocabulary per term than their peers relying only on lessons.

Webb (2008) found that reading one graded reader (around 8,000–10,000 running words) resulted in incidental acquisition of 40–50 new words.

Listening to podcasts like InnerFrench with transcripts, maintaining a digital spaced repetition deck (e.g., The Language Gym or Anki), or writing short diary entries using newly learned words powerfully extend classroom learning into deep consolidation.

6. Learners’ Mastery of Word-Learning Strategies

Research consistently shows that learners who use conscious strategies — like creating mental imagery, using semantic grouping, deducing from context, and self-quizzing — outperform peers by margins as large as 50% (Gu & Johnson, 1996; Schmitt, 2000).

Explicit instruction and modelling of strategies (e.g., visualising lutter by imagining a boxing match, or mapping synonyms and antonyms) can dramatically enhance vocabulary depth and flexibility.

Learners must not only be taught words — but also taught how to learn words effectively.

Table 3 – Most researched word learning strategies

7. Learners’ Current Level of Proficiency

Higher proficiency enables deeper and faster vocabulary acquisition. Laufer (1998) found that intermediate learners could infer meaning from context approximately twice as accurately as beginners.

Advanced learners can make use of suffixes (-ment, -tion), prefixes (re-, dé-) and infer unknown words by analogy with known ones, making them far more efficient in incidental vocabulary learning.

Curriculum scaffolding should therefore carefully match input difficulty to learners’ inferencing abilities.

8. Learners’ L1 Vocabulary and Literacy

Strong L1 literacy correlates positively with L2 vocabulary acquisition.

Bilinguals or literate L1 learners more readily notice morphological patterns (e.g., entraide — mutual help, métissage — cultural mixing) and leverage semantic clues to decode new words.

Cummins’ (2000) Common Underlying Proficiency model suggests that cross-linguistic transfer of cognitive skills explains much of the variance in vocabulary learning success rates.

9. Learners’ Working Memory

Working memory capacity — particularly phonological memory — predicts the ability to rehearse and consolidate novel word forms.

Gathercole and Baddeley (1990) showed that phonological memory accounted for 40–50% of differences in new word learning rates among children and adults.

Training memory using rhythmical drills, chants, and repetition bursts significantly boosts early-stage vocabulary acquisition.

10. Learners’ Attitudes to Word Learning

Dörnyei (2005) emphasised that motivation was one of the strongest mediators of vocabulary acquisition: highly motivated learners devoted up to twice as much time to vocabulary practice outside class and retained words 25–30% better.

Simple motivational practices — setting achievable goals, celebrating milestones (e.g., Word Wizard awards), linking vocabulary to learners’ interests (e.g., sports, music, travel) — foster higher learner engagement and persistence.

11. Learners’ L1(s)

The influence of a learner’s first language (L1) on vocabulary acquisition depends largely on the degree of typological similarity between the L1 and the target language. Ringbom (2007) showed that when learners’ L1 and L2 share cognates or similar morphosyntactic structures, vocabulary transfer is facilitated, sometimes accounting for up to 25% faster acquisition during early learning stages.

However, when no such cognate scaffolding exists, as in the case of learners moving from a non-Indo-European L1 (e.g., Mandarin, Korean) to French, explicit vocabulary learning becomes significantly harder.

Thus, a Spanish learner may infer déjeuner (to have lunch) through analogy with desayuno, whereas a Japanese learner has no such linguistic support and must build word knowledge from scratch.

Nevertheless, studies (Lindqvist, 2009) demonstrate that cross-linguistic training — teaching students to consciously notice similarities and differences — can substantially reduce this gap, boosting the speed of acquisition even for distant-language learners.

12. Curriculum and Assessment Focus

Curriculum design and assessment philosophy exert profound effects on vocabulary learning trajectories. When curricula focus heavily on explicit vocabulary recycling, strategy training, and meaningful usage, learners’ gains in both receptive and productive vocabulary are markedly higher (Carlo et al., 2004).

Conversely, traditional curricula that prioritize memorisation of isolated word lists, followed by discrete-point testing (e.g., fill-the-blank items requiring only recall of definitions), tend to produce shallow and transient vocabulary knowledge (Schmitt, 2010).

Evidence from Stæhr (2009) shows that when assessments reward active, flexible usage of vocabulary (e.g., writing tasks, oral summaries), learners acquire and retain 20–30% more words compared to cohorts evaluated solely through isolated vocabulary tests.

Curriculum designers must therefore weave rich, usage-oriented vocabulary tasks into both teaching sequences and assessments to optimise acquisition.

13. Learners’ Socio-Economic Factors

Socio-economic status (SES) undeniably impacts early vocabulary development. Hart and Risley (1995) found that by age three, children from high-SES households had been exposed to around 30 million more words than children from lower-SES backgrounds, a gap that persists and compounds into adolescence.

However, in the context of second language learning, SES effects can be mitigated substantially.

Structured interventions focusing on explicit vocabulary teaching, extensive listening and reading programs, strategy instruction, and repeated retrieval practice have been shown to narrow vocabulary gaps within as little as two years (Stahl & Fairbanks, 1986).

Thus, while learners’ socio-economic backgrounds shape their starting points, principled teaching can dramatically alter their vocabulary growth trajectories.

14. Learners’ Age

Age affects vocabulary acquisition differently depending on the stage of learning and the nature of exposure.

Adults often demonstrate faster initial acquisition rates due to more developed working memory, greater metalinguistic awareness, and stronger inferencing skills (Singleton, 2001). For instance, older learners can explicitly deduce that entraîner and entraîneur share the root entraîne- and thus infer meanings more easily.

The greater working memory capacity, does give older learners (see Table 4 below) a significant advantage in formal,acquisition-poor environments. However, children who are immersed in a rich L2 environment from an early age often surpass adults in achieving native-like depth, automaticity, and nuance over time (Muñoz, 2006). They benefit from neural plasticity and may build implicit, proceduralised word knowledge more effectively if exposed early and intensively.

Thus, while age offers certain cognitive advantages or disadvantages depending on the stage and setting, it is the quality and quantity of input, engagement, and recycling that ultimately determine long-term vocabulary outcomes.

Table 4 – Ease of vocabulary learning as a function of age–related working memory capacity

| Age | Typical Working Memory Capacity | Ease of Vocabulary Learning | Research Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 years old | Limited (2–3 new lexical items reliably at once); phonological loop still developing | Struggles to retain multiple unfamiliar words without very heavy scaffolding and multimodal reinforcement; benefits from visual aids, repetition, and chunking | Gathercole & Baddeley (1990); Alloway et al. (2006) |

| 11 years old | Improved (3–5 new lexical items at once); faster rehearsal speed; better chunking ability | Can retain moderate sets of new words (~4–6 words per exposure) if supported by strong context and phonological support; still vulnerable to overload | Gathercole (1995); Service (1992) |

| 16 years old | Adult-like capacity (5–7 new lexical items at once); strategic rehearsal and retrieval emerge | Can learn larger vocabulary batches (~6–10 words) with limited scaffolding; benefits more from self-testing and morphological awareness strategies | Baddeley (2003); Ellis (2002); Nation (2001) |

Conclusion

Vocabulary acquisition is a multidimensional process, shaped by a combination of word-related, learner-related, instructional, and environmental variables.

However, the factors do not carry equal weight.

Frequency of exposure, high-quality instruction, time-on-task, and deep, meaningful engagement with vocabulary emerge as the most powerful and controllable levers for promoting robust lexical growth.

While learner-specific factors like L1 background, working memory, age, and socio-economic context influence the rate and route of vocabulary learning, they are consistently secondary to the curriculum, pedagogy, and cognitive practices implemented.

For teachers, this ranking provides a clear roadmap: focus energy and time on ensuring rich input, principled recycling, frequent retrieval, strategy training, and motivation-enhancing practices.

By doing so, we dramatically increase our learners’ chances of building a powerful, flexible, and enduring lexicon — the foundation upon which true language mastery rests.

Summary table

You must be logged in to post a comment.