In recent years, neuroscience has begun to reshape how we think about language learning—not just in theory, but in practical terms that can transform classroom teaching. We now know far more about how the brain perceives, stores, and retrieves language than ever before. And yet, many of these discoveries haven’t filtered down to everyday classroom practice. This article explores eleven of the most surprising—and educationally relevant—facts about how the brain processes language, with a particular eye toward their implications for second language instruction. These are findings that challenge long-held assumptions and offer new, research-informed pathways for making language learning more efficient, engaging, and brain-friendly. Yet many of these discoveries remain under the radar for most language teachers.

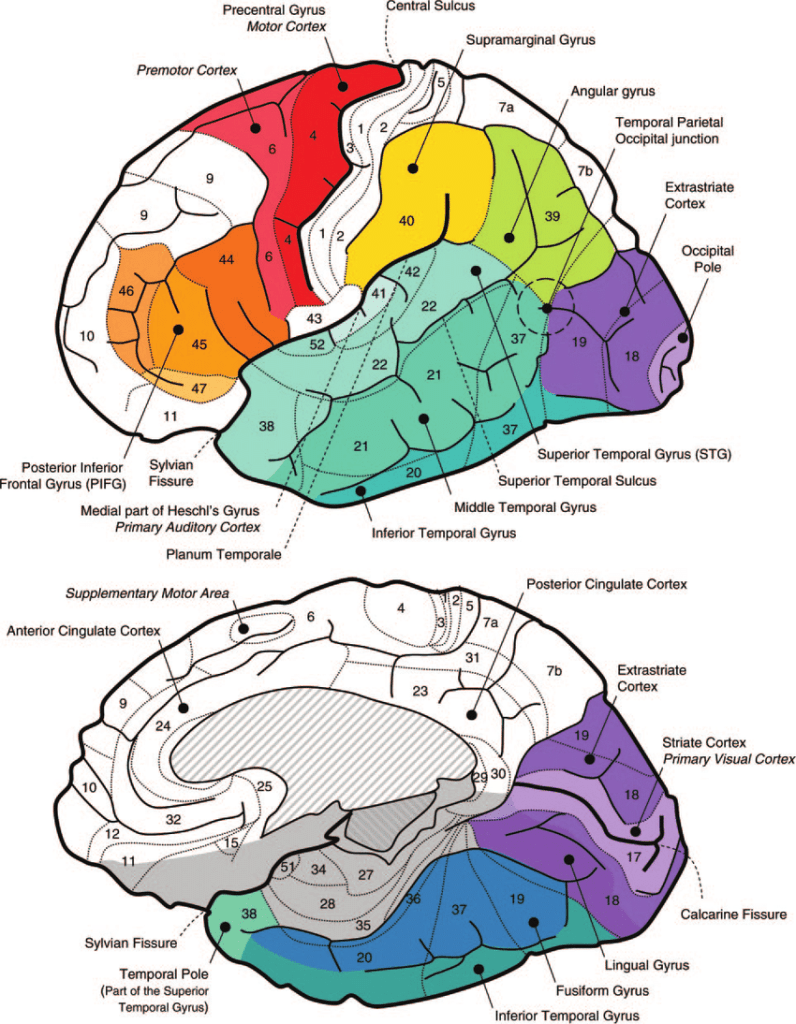

Figure 1 – Main resions involved in language processing

Eleven Surprising Facts About How the Brain Processes Language

What does neuroscience really tell us about how the brain handles language—and why does it matter for teachers? Much of what we once believed about language learning has been upended by findings in neuroimaging and psycholinguistics. For example, the idea that grammar needs to come before meaning, or that listening and speaking are separate skills, has little basis in how the brain actually processes language. Although traditional textbooks have long referred to a “language centre,” such as Broca’s or Wernicke’s area, modern neuroscience reveals that language is a whole-brain activity. Language comprehension and production draw on motor, auditory, memory, and visual systems, often simultaneously. This complexity calls for equally nuanced approaches to teaching.—and why does it matter for teachers? Much of what we once believed about language learning has been upended by findings in neuroimaging and psycholinguistics.

Below are eleven evidence-based insights into how the brain processes language. Each reveals something counterintuitive or overlooked in traditional language teaching and points towards a more brain-aligned approach.

1. Language is not stored in a single “language centre”: Although Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas were once thought to be the sole language hubs, modern neuroscience reveals that language engages a widespread network of regions across the brain. These include areas responsible for motor control, auditory processing, memory retrieval, and even visual perception. This interconnectedness supports the use of multimodal input in the classroom and challenges the long-held idea of a single language processing centre.—including those involved in motor control, auditory processing, memory, and even visual perception.

Table 1 – Key language-processing hubs and their functions

| Brain Region | Function |

|---|---|

| Broca’s Area | Produces speech, grammar processing, and syntactic structuring |

| Wernicke’s Area | Processes language meaning and semantic comprehension |

| Motor Cortex | Supports articulation and the planning of physical speech actions |

| Auditory Cortex | Detects and decodes spoken language input |

| Basal Ganglia | Supports procedural learning, especially rule-based grammar |

| Hippocampus | Encodes and consolidates new vocabulary (declarative memory) |

| Angular Gyrus | Supports reading comprehension and semantic integration |

| Prefrontal Cortex | Handles executive control, working memory, and cognitive switching |

2. Grammar and vocabulary are processed in separate but coordinated systems: Neuroimaging shows that grammar is largely handled by procedural memory systems (e.g., basal ganglia and frontal cortex), while vocabulary relies more on declarative memory (e.g., temporal lobe structures). This dissociation helps explain why students may show uneven development between grammatical accuracy and lexical knowledge. This has important implications for second language instruction

3. Complex grammar is processed differently from simple grammar: More complex grammatical constructions—such as embedded clauses, passives, and subject-object reversals—recruit additional frontal and parietal regions of the brain compared to simpler syntax. This suggests that more demanding structures impose greater cognitive load, requiring more time and practice to proceduralise. The complexity of the input directly influences which neural systems are taxed during language comprehension. This is key when considering inclusivity and differentiation

4. Listening and speaking activate overlapping neural circuits: Research shows that hearing language activates many of the same regions as speaking it. This is key, as it helps explain why frequent listening can strengthen oral fluency and makes it imperative, at lowers levels of proficiency especially, to provide lots of aural input prior to staging speaking activities

5. Formulaic chunks are processed more efficiently: The brain stores frequently used expressions as single units, reducing the processing load and speeding up retrieval. This makes chunking not just helpful, but neurologically efficient. This is crucial when considering how to promote oral fluency

6. Bilinguals use both languages even when speaking one: The bilingual brain constantly activates both linguistic systems, requiring inhibition of the irrelevant one. This cross-activation explains why interference happens and why it’s normal—not a failure. This also speaks to the importance of staging priming tasks, prior to productive retrieval, aimed at mitigating L2 interference

7. Learning a second language reshapes the brain: L2 acquisition leads to structural brain changes, such as increased grey matter in language-relevant areas. The brain adapts physically to accommodate new linguistic systems, particularly with sustained exposure.

8. The brain predicts upcoming words: Language processing isn’t passive; it’s predictive. We subconsciously anticipate what comes next in a sentence based on prior context, a habit that can be developed through consistent input routines. This phenomenon, called ballistic processing, point to the inefficiency of teaching words in isolation

9. Inner speech activates speech areas: When learners silently read or mentally rehearse phrases, they’re engaging the same neural circuits as in actual speech. This means “thinking in the language” is a real and useful skill.

10. Emotionally charged words are remembered better: Emotional engagement enhances memory encoding, particularly for vocabulary. This is due to interaction between language centres and the amygdala, the brain’s emotion processor.

11. Native and second languages are processed differently —at first: While early L2 learning is effortful and uses frontal executive control regions, over time the brain automates the process and shifts to more native-like processing patterns. This points to the importance of embedding a fluency strand in the L2 curriculum

Table 2 – 11 facts about the cognition of L2 processing

| Language is not stored in a single “language centre” | Language processing is distributed across a widespread network including motor, auditory, and memory systems. | Hickok & Poeppel (2007); Pulvermüller (2005) |

| Grammar and vocabulary are processed in separate but coordinated systems | Grammar is supported by procedural memory, vocabulary by declarative memory. This helps explain uneven development between grammar and lexis. | Ullman (2001); Friederici (2011) |

| Complex grammar is processed differently from simple grammar | Complex syntactic structures engage additional frontal and parietal regions, indicating that increased grammatical difficulty raises cognitive processing demands. This distinction warrants distinct instructional pacing. | Makuuchi et al. (2009); Friederici (2011) |

| Listening and speaking activate overlapping neural circuits | Listening improves speaking fluency via shared brain regions. | Wilson et al. (2004); Skipper et al. (2007) |

| Formulaic chunks are processed more efficiently | The brain stores common phrases as single units. | Wray (2002); Van Lancker Sidtis (2004) |

| Bilinguals use both languages even when speaking one | Words and grammar rules from both languages compete in real time. | Marian & Spivey (2003); Kroll et al. (2008) |

| Learning a second language reshapes the brain | Bilingualism increases grey matter density in language areas. | Mechelli et al. (2004); Li et al. (2014) |

| The brain predicts upcoming words | Language processing is anticipatory, not just reactive. | Federmeier & Kutas (1999); DeLong et al. (2005) |

| Inner speech activates speech areas | The brain simulates actual speech during silent reading or thought. | McGuire et al. (1996); Tian & Poeppel (2010) |

| Emotionally charged words are remembered better | Emotional words enhance memory through amygdala interaction. | Kensinger & Corkin (2003); Schmidt (1994) |

| Native and second languages are processed differently | Second language processing begins more effortfully but becomes more automatic. | Abutalebi (2008); Perani et al. (1998) |

Implications for Teaching Practice

Each of these neuroscience insights carries direct, actionable consequences for classroom practice:

- Distributed processing: Since language processing recruits a wide network of brain areas—not just a single “language centre”—teachers should engage multiple sensory pathways in instruction. This includes combining spoken input with images, gestures, movement, and physical response. Techniques like Total Physical Response (TPR), captioned videos, and hands-on tasks can stimulate motor, auditory, and visual systems simultaneously, promoting deeper encoding.

- Grammar–vocabulary dissociation: Grammar and vocabulary are handled by different memory systems—grammar by procedural memory, vocabulary by declarative memory. This means teachers should scaffold them differently. Vocabulary benefits from explicit, semantic support and spaced recall; grammar needs structured, meaningful repetition to embed patterns into long-term procedural memory.

- Complexity effects in grammar processing: As grammar becomes more complex, it activates additional brain areas and imposes higher processing loads. Teachers should introduce difficult syntax gradually, recycle it frequently, and provide ample opportunities for practice with rich context support. Expecting instant mastery of complex structures ignores the brain’s need for time and repetition when integrating cognitively demanding forms.

- Shared circuits for listening and speaking: Because speaking and listening share overlapping neural substrates, increasing high-quality listening input will directly support speaking development. This underscores the value of listening-rich environments, where learners hear varied and comprehensible speech in different voices and accents. Listening should be active, task-supported, and interleaved with speaking practice.

- Formulaic chunking: The brain processes formulaic language more efficiently than novel constructions. Teachers should focus on teaching useful sentence stems, routines, and chunks (e.g., “I think that…”, “Can I have…?”, “Yesterday I went…”) rather than isolated words or grammar rules. Recycling these chunks across topics helps develop fluency and reduces cognitive load during communication.

- Cross-language activation: Bilinguals constantly juggle both languages, even when using only one. This means that interference, code-switching, and cross-linguistic transfer are normal and should be addressed explicitly. Teachers can help by highlighting false friends, contrasting structures, and encouraging metalinguistic reflection—turning interference into an opportunity for deeper learning.

- Brain plasticity: The brain physically adapts to language learning over time, especially when input is regular and meaningful. This reinforces the need for consistent, sustained exposure over cramming or irregular practice. Curriculum planners should structure language input so it’s cumulative, recycled, and spaced, rather than fragmented into discrete, unconnected units.

- Prediction in comprehension: The brain doesn’t passively wait for words—it predicts them based on context. To leverage this, teachers should create routines and patterns that help learners anticipate upcoming content. Narrow listening, cloze prediction, trapdoor and question-driven reading are ideal strategies to engage predictive processing.

- Inner speech engagement: Silent reading, inner translation, and internal rehearsal activate many of the same brain areas as speaking aloud. Teachers can use this to their advantage by encouraging learners to “speak in their heads”—especially during writing planning, reading, and test-taking. Activities like mental rehearsal, inner retelling, or visualising a conversation can build fluency without external output.

- Emotional salience: Emotionally charged words and contexts are more memorable. This implies that lessons should provoke emotional engagement as much as possible —through humour, controversy, personal stories, or high-stakes decision-making. Vocabulary linked to emotional or autobiographical memory is more likely to stick.

- Different processing modes: Initially, second languages are processed more consciously and effortfully than native ones. Teachers should provide scaffolding, repetition, and opportunities for proceduralisation. Over time, as learners automate key forms and routines, they become freer to focus on meaning and interaction. It’s crucial to manage expectations and ensure learners don’t feel frustrated by early slowness.

Conclusion

The way the brain processes language is far more dynamic, distributed, and strategic than once believed. For educators, this means moving away from rigid grammar-first or memorisation-heavy practices and instead embracing methodologies grounded in how the brain naturally acquires, stores, and retrieves language. From chunking and multisensory input to emotional engagement and prediction-based practice, the neuroscience of language learning urges us to teach in ways that align with the brain’s architecture.

Among the most surprising and impactful findings are:

- The separation of grammar and vocabulary systems – This insight directly shaped the core principle in EPI of treating lexis and syntax as distinct strands, each requiring different instructional strategies and modes of recycling.

- Complex grammar processing involves different neural regions – This has informed EPI’s emphasis on staged grammatical progression and long-term recycling of more difficult structures to avoid overload.

- Formulaic language is processed more efficiently – This discovery supports EPI’s focus on sentence builders, high-frequency chunks, and fluency through repetition of ready-made expressions.

Each of these findings continues to shape how Extensive Processing Instruction supports learners in developing spontaneous, confident, and fluent language use through principled, neuroscience-aligned methods.

References

- Abutalebi, J. (2008). Neural aspects of second language representation and language control. Acta Psychologica, 128(3), 466–478.

- DeLong, K. A., Urbach, T. P., & Kutas, M. (2005). Probabilistic word pre-activation. Nature Neuroscience, 8(8), 1117–1121.

- Federmeier, K. D., & Kutas, M. (1999). A rose by any other name: Meaning in the absence of syntax. Memory & Cognition, 27(4), 538–550.

- Friederici, A. D. (2002). Towards a neural basis of auditory sentence processing. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6(2), 78–84.

- Hickok, G., & Poeppel, D. (2007). The cortical organization of speech processing. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 8(5), 393–402.

- Kensinger, E. A., & Corkin, S. (2003). Memory enhancement for emotional words. Neuropsychologia, 41(5), 593–610.

- Kroll, J. F., Bobb, S. C., & Wodniecka, Z. (2008). Language selectivity in bilingual speech. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(2), 100–104.

- Kutas, M., & Hillyard, S. A. (1980). Reading senseless sentences: Brain potentials reflect semantic incongruity. Science, 207(4427), 203–205.

- Li, P., Legault, J., & Litcofsky, K. A. (2014). Neuroplasticity as a function of second language learning. Bilingualism, 17(2), 234–250.

- Marian, V., & Spivey, M. (2003). Competing activation in bilingual language processing. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 6(2), 97–115.

- McGuire, P. K. et al. (1996). Functional neuroanatomy of inner speech and auditory verbal imagery. Psychological Medicine, 26(1), 29–38.

- Mechelli, A. et al. (2004). Structural plasticity in the bilingual brain. Nature, 431(7010), 757.

- Perani, D. et al. (1998). The bilingual brain: Proficiency and age of acquisition. Brain, 121(10), 1841–1852.

- Pulvermüller, F. (2005). Brain mechanisms linking language and action. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6(7), 576–582.

- Schmidt, S. R. (1994). Effects of emotion on memory: Recognition of taboo words. Memory & Cognition, 22(3), 390–403.

- Skipper, J. I., Nusbaum, H. C., & Small, S. L. (2007). Listening to talking faces. NeuroImage, 36(3), 1145–1155.

- Tian, X., & Poeppel, D. (2010). Mental imagery of speech. NeuroImage, 49(1), 994–1005.

- Van Lancker Sidtis, D. (2004). When novel sentences spoken become formulaic. Language & Communication, 24(4), 207–223.

- Wilson, S. M. et al. (2004). Listening to speech activates motor areas. Nature Neuroscience, 7(7), 701–702.

- Wray, A. (2002). Formulaic Language and the Lexicon. Cambridge University Press.

You must be logged in to post a comment.