Introduction

Extensive Processing Instruction (EPI) is a research-informed approach to language teaching that has gained significant traction in recent years. With its growing success in classrooms around the world, EPI continues to inspire educators who seek a more effective and inclusive way to build real language competence. However, as with any innovative pedagogical model, it has also become a target of misunderstanding—and, in some cases, of politically motivated misrepresentation. These misconceptions are sometimes spread deliberately by individuals or groups resistant to pedagogical change or who perceive EPI as a challenge to entrenched norms and commercial interests.

Even influential figures in the educational landscape have occasionally offered remarks that appear to misrepresent both the spirit and the substance of EPI. Such misunderstandings risk distorting the public discourse around effective language teaching, especially when they gain traction in professional networks or inspectorate frameworks.

This post aims to clarify thirteen of the most common myths surrounding EPI. It draws on extensive research evidence to highlight the approach’s effectiveness, flexibility, and strong theoretical foundation. In addition to scholarly perspectives, this post is grounded in the lived experiences of teachers across the globe. Testimonials shared recently in the Global Innovative Language Teachers Facebook group—by practitioners from Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Middle East, South-East Asia, and the UK—offer compelling anecdotal evidence of EPI’s positive impact on student learning and teacher confidence.

Thirteen misconceptions about EPI

1. Misconception: EPI is just about repetition and drills

Reality: While EPI does rely on repetition, it is purposeful, structured, and embedded in meaningful contexts. The repetition is not mechanical but designed to promote fluency, automaticity, and a deeper understanding of grammatical structures and vocabulary chunks. Techniques like input flood and task repetition, as well as tasks like narrow listening, sentence puzzles, jigsaw reading, dictogloss, chunking aloud, oral retrieval practice and fluency games ensure the language is processed deeply and repeatedly, but in ways that keep learners engaged and focused on communication. Repetition is always tied to meaning, not just form.

Research Insight: Repeated exposure to meaningful language input enhances retention and fluency. Research by Barcroft (2007) and Nation (2013) supports the value of input-based learning, while studies on retrieval practice (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006) highlight its impact on long-term memory.

2. Misconception: EPI ignores grammar

Reality: EPI teaches grammar implicitly through repeated exposure to high-frequency structures in meaningful contexts. Learners internalize rules without overt instruction initially, and grammar points are often clarified after the chunks have been acquired, making the grammar more memorable and meaningful. EPI teaches grammar in a way that is cognizant of processability theory, learner readiness, and cognitive load theory. It introduces grammar at a more realistic pace, aiming to entrench a manageable set of non-negotiables each term. This approach facilitates routinisation in an inclusive manner, ensuring that all learners—regardless of background—can consolidate key structures. The process involves intensive and extensive teaching through spaced retrieval over a longer period of time than traditional textbooks usually allow, ensuring that grammatical knowledge is retained and applied fluently.

Research Insight: VanPatten (2002) emphasizes the importance of input in grammar acquisition, and Krashen’s Input Hypothesis (1982) supports the idea that comprehensible input is key to developing grammatical accuracy.

Figure 1 – EPI enhances students’ grammar competence but not at the cost of fluency and spontaneity

3. Misconception: EPI is only suitable for beginners

Reality: EPI can be scaled to all levels of proficiency. For beginners, it introduces foundational chunks and sentence structures. At intermediate and advanced levels, it incorporates more complex syntax, idiomatic expressions, and nuanced communicative tasks. Teachers can easily adapt the language and cognitive load of the tasks to match learner ability, making it an effective framework for all stages of language acquisition.

Research Insight: Ellis (1996) and Boers & Lindstromberg (2008) show that chunk-based and lexical approaches are beneficial across all stages of learning, not just at the beginner level.

Figure 2 – EPI makes grammar accessible and learnable through pop-up grammar, syntactic priming and full-blown grammar lessons. The difference: grammar is taught intensively after the taregt chunks have been routinised

4. Misconception: It neglects spontaneous speech

Reality: EPI explicitly develops spontaneous speech through careful scaffolding. Learners progress from controlled production to semi-controlled and finally to free output. Activities such as oral translation slaloms, communicative pair tasks, and rephrasing challenges foster fluency and flexibility. Because students are already familiar with the chunks and structures, they can speak more confidently and accurately when engaging in real-time communication.

Research Insight: Automatization theory (DeKeyser, 2001) and models of skill acquisition (Schneider & Shiffrin, 1977) show that repeated practice with meaningful output leads to spontaneous language use.

5. Misconception: EPI doesn’t prepare students for exams

Reality: EPI builds the foundational skills—listening comprehension, vocabulary range, grammatical accuracy, and fluency—that are essential for exam success. In fact, many of the core EPI tasks, such as reading aloud, dictation, translation, picture-based speaking, semi-structured communicative tasks and guided speaking activities (e.g. role plays with English prompts), have long been a part of the EPI approach—well before the design of the most recent GCSE reforms. These tasks are closely aligned with the exact formats and skills now tested in the new exam specifications. Thus, rather than being exam-agnostic, EPI actually anticipated the current exam model and provides students with repeated, structured exposure to all its task types.

Research Insight: Laufer & Nation (1995) and Hulstijn (2001) show that vocabulary acquisition and automaticity are key predictors of exam success.

6. Misconception: Students memorize phrases without understanding

Reality: Understanding is central to EPI. Activities such as meaning-matching, sentence building, faulty translation correction, and gap-fills ensure learners comprehend what they are using. The chunks are not taught in isolation but in contexts that require students to process meaning, interpret nuance, and use them flexibly. This type of learning leads to deeper retention and transferability of language skills.

Research Insight: Deep processing theory (Craik & Tulving, 1975) shows that learners retain information better when they understand and manipulate meaning rather than memorizing form alone.

7. Misconception: EPI requires technology

Reality: EPI is fully adaptable to low-tech or no-tech classrooms. Although platforms like The Language Gym and sentencebuilders.com provide digital tools, all EPI tasks can be delivered using printed worksheets, whiteboards, and simple classroom routines. The power of EPI lies in the task design and sequencing, not the medium of delivery, making it accessible and sustainable in any educational setting.

Research Insight: Pashler et al. (2007) emphasize that instructional effectiveness is driven more by design principles than delivery platforms.

8. Misconception: EPI is rigid and prescriptive

Reality: EPI is a highly flexible and adaptable framework. Teachers can modify the order, pace, and nature of activities based on their students’ needs, curriculum demands, and teaching style. It provides a structured but open approach that encourages professional judgment and creativity, allowing for culturally responsive and differentiated instruction.

Research Insight: Tomlinson (2011) argues that effective language teaching must be adaptable and sensitive to context, which aligns well with EPI’s flexible structure.

9. Misconception: EPI ignores culture

Reality: EPI integrates cultural content naturally by embedding chunks and grammar within authentic, culturally rich contexts. Whether discussing festivals, daily routines, or social values, EPI promotes intercultural awareness through language. Tasks are designed to be both linguistically and culturally meaningful, helping students connect language learning to real-world understanding.

Research Insight: Byram (1997) and Kramsch (1993) underline the inseparability of language and culture in language learning.

10. Misconception: EPI is boring or mechanical

Reality: EPI lessons are dynamic, varied, and engaging. The repetition is disguised through games, puzzles, problem-solving, and communicative challenges that stimulate interest and participation. Because students experience frequent success and are actively involved in tasks, motivation remains high. EPI activities are designed to balance fun with serious language development.

Research Insight: Dörnyei & Ushioda (2011) demonstrate that motivation increases when learners experience success and engagement, both core features of EPI tasks.

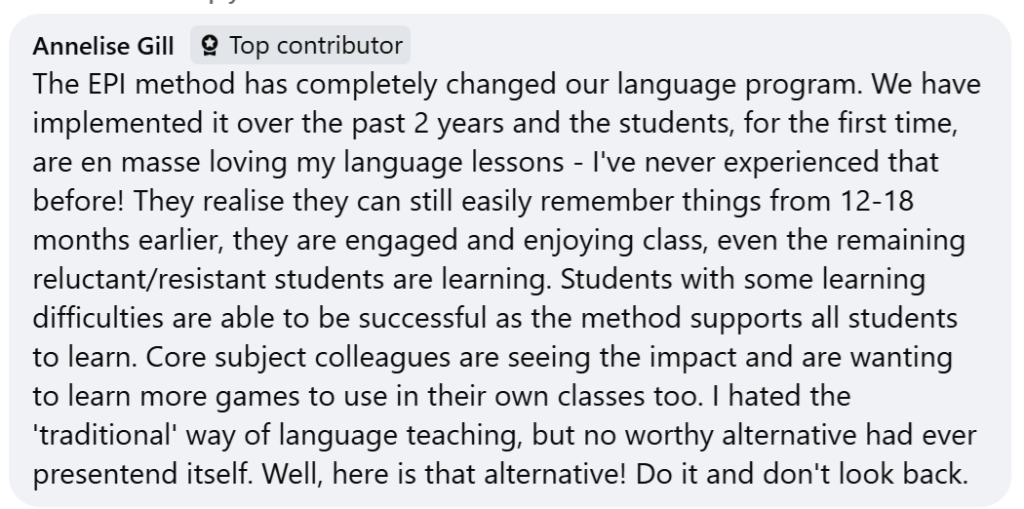

Figures 3 and 4 – As this testimonials indicate, EPI favourably impacts motivation

11. Misconception: EPI can’t be used with textbooks

Reality: EPI complements textbooks by transforming textbook content into communicative chunks and processing-rich tasks. Teachers can lift vocabulary and grammar points from a textbook and restructure them into EPI-style lessons, enhancing both engagement and retention. This allows departments bound to textbook schemes of work to modernize their delivery while meeting institutional requirements.

Research Insight: Tomlinson (2003) supports the adaptation of textbook content to suit learners’ needs and increase task-based effectiveness.

12. Misconception: EPI isn’t research-based

Reality: EPI draws from robust research in second language acquisition, cognitive science, and memory studies. Principles like retrieval practice, input enhancement, spaced repetition, and chunking are core to EPI and supported by decades of empirical research. The method is a practitioner-led synthesis of evidence-informed strategies tailored to real classroom contexts.

Research Insight: Roediger & Karpicke (2006), Sharwood Smith (1993), and Schmidt (1990) provide the cognitive and SLA foundations that EPI builds upon, particularly in retrieval, input, and noticing theory.

13. Misconception: The MARSEARS cycle makes EPI too slow

Reality: While the MARSEARS cycle involves deliberate steps to guide processing, it does not slow down learning when planned and sequenced effectively. On the contrary, the cycle ensures repeated, varied processing of the same content across modalities and contexts, leading to stronger long-term retention. This depth of processing means that, by the time students reach Years 10 and 11, they do not need to relearn foundational content. Many traditional approaches waste valuable curriculum time reteaching grammar, vocabulary, and structures that were superficially taught and quickly forgotten. EPI front-loads robust learning that frees up time for deeper work later on.

Research Insight: Research on spaced repetition and memory consolidation (Cepeda et al., 2006) and long-term retention (Carpenter et al., 2012) confirms that distributed and repeated exposure is key to enduring mastery.

Summary Table

The following table provides a quick-reference summary of each misconception, the corresponding reality, and a key research insight:

| No. | Misconception | Reality (Summary) | Research Insight (Summary) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EPI is just about repetition and drills | Repetition is meaningful, engaging, and tied to context. | Deep, meaningful repetition enhances long-term retention. |

| 2 | EPI ignores grammar | Grammar is taught through chunks, with attention to readiness, cognitive load, and long-term retrieval. | Input and timing matter more than isolated grammar drills. |

| 3 | Only for beginners | Tasks can be adapted for any proficiency level. | Lexical approaches benefit learners across stages. |

| 4 | Neglects spontaneous speech | Scaffolded tasks build confidence for fluent real-time speech. | Practice with input/output leads to automaticity. |

| 5 | Doesn’t prepare for exams | Longstanding tasks align closely with current GCSE requirements. | Vocabulary fluency supports exam success. |

| 6 | Students memorize without understanding | Tasks ensure deep processing of meaning. | Deeper semantic processing leads to stronger retention. |

| 7 | Requires technology | Fully adaptable to low/no-tech environments. | Instructional design trumps delivery format. |

| 8 | Rigid and prescriptive | EPI is flexible and teacher-adaptable. | Effective methods adapt to local context. |

| 9 | Ignores culture | Cultural content is naturally embedded in communicative tasks. | Culture and language are inseparable. |

| 10 | Boring or mechanical | Activities are engaging, interactive, and varied. | Success and variety increase motivation. |

| 11 | Can’t be used with textbooks | Textbook content can be reframed through EPI structures. | Adapting resources enhances learning outcomes. |

| 12 | Not research-based | Built on principles from SLA, memory science, and cognitive psychology. | Robust evidence supports EPI foundations. |

| 13 | The MARSEARS cycle is too slow | With planning, it boosts durable retention and avoids re-teaching. | Spaced, repeated exposure consolidates mastery and saves time long-term. |

Conclusion

Extensive Processing Instruction is not a trend—it is a principled, flexible, and evidence-informed framework for building real language competence. Far from being a rigid or narrow methodology, it is built on robust psycholinguistic and pedagogical foundations that adapt to learners’ needs and institutional constraints. When implemented with fidelity and creativity, EPI does not just meet curricular demands—it exceeds them, offering a path to deep, lasting, and confident language use. As a teacher put it in one of the testimonials above, it is not a silver bullet, but it appears to enhance both teacher and student’s self-efficacy and motivation.

References

Barcroft, J. (2007). Effects of opportunities for word retrieval during second language vocabulary learning. Language Learning, 57(S1), 35–56.

Boers, F., & Lindstromberg, S. (2008). Cognitive Linguistic Approaches to Teaching Vocabulary and Phraseology. Mouton de Gruyter.

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Multilingual Matters.

Carpenter, S. K., Cepeda, N. J., Rohrer, D., Kang, S. H. K., & Pashler, H. (2012). Using spacing to enhance diverse forms of learning: Review of recent research and implications for instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 24(3), 369–378.

Craik, F. I., & Tulving, E. (1975). Depth of processing and the retention of words in episodic memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 104(3), 268–294.

DeKeyser, R. M. (2001). Automaticity and automatization. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and Second Language Instruction. Cambridge University Press.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2011). Teaching and Researching Motivation (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Ellis, N. C. (1996). Sequencing in SLA: Phonological memory, chunking and points of order. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 18(1), 91–126.

Hulstijn, J. H. (2001). Intentional and incidental second-language vocabulary learning: A reappraisal of elaboration, rehearsal and automaticity. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and Second Language Instruction. Cambridge University Press.

Kramsch, C. (1993). Context and Culture in Language Teaching. Oxford University Press.

Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Pergamon.

Laufer, B., & Nation, P. (1995). Vocabulary size and use: Lexical richness in L2 written production. Applied Linguistics, 16(3), 307–322.

Nation, I. S. P. (2013). Learning Vocabulary in Another Language (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Pashler, H., Bain, P. M., Bottge, B. A., et al. (2007). Organizing Instruction and Study to Improve Student Learning (NCER 2007-2004). U.S. Department of Education.

Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test-enhanced learning: Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science, 17(3), 249–255.

Schmidt, R. (1990). The role of consciousness in second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 11(2), 129–158.

Schneider, W., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1977). Controlled and automatic human information processing: Detection, search, and attention. Psychological Review, 84(1), 1–66.

Sharwood Smith, M. (1993). Input enhancement in instructed SLA: Theoretical bases. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 15(2), 165–179.

Tomlinson, B. (2003). Developing principled frameworks for materials development. In B. Tomlinson (Ed.), Developing Materials for Language Teaching. Continuum.

Tomlinson, B. (2011). Materials Development in Language Teaching (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

VanPatten, B. (2002). Processing instruction: An update. Language Learning, 52(4), 755–803.