Introduction

Classroom management in Modern Foreign Languages is not only about discipline — it is more about creating the right situation where learning can really happen. Because MFL lessons usually have speaking, interaction, and the use of the target language, they are often more lively compared to other subjects. This liveliness is like a double-edged sword: it brings a lot of energy, but it also opens the door to distraction if routines, clarity, and pace are missing. Research from general pedagogy and also from language teaching shows time and again a set of habits that good MFL teachers normally use. What follows is a discussion of these habits, showing how small and steady actions may help classrooms to be calmer, more engaging, and productive places.

1.Establish Clear and Steady Routines

• Habit: Greeting at the door, same starter(s) each lesson (retrieval task, drill, listening warm-up). This is something that all of my mentors at the beginning of my teaching career always emphasized the importance of and they were right. The few times I didn’t do that because I was busy setting up the computer or dealing with a student, it did impact negatively the beginning of my lessons.

• Why it works: Reduces uncertainty, creates order, and cuts downtime where misbehaviour can creep in.

• Research: Marzano & Marzano (2003) found that when teachers are consistent with routines, lessons run more smoothly and students’ behaviour problems are reduced.

• When it’s missing: Mr Patel once skipped his usual retrieval starter and let students settle themselves, and within minutes half were chatting and looking lost! In my experience, routines may save much more time than they waste, because they prevent the chaos that always takes longer to fix. Isn’t it better to spend two minutes on a starter than ten minutes calming things down later?

2. Use Target Language Purposefully and Simply

• Habit: High but comprehensible TL use with clear non-verbal scaffolds (gestures, visuals, sentence frames). If what you are saying in the target language and too complicated to convey through gestures or other visuals, simply use the students’ L1. Remember: no students should be left behind, confused or irritated by the target language explanation. Not even one.

• Why it works: Keeps students engaged in “doing languages” rather than “doing discipline,” and predictability reduces worry and resistance.

• Research : Macaro (2018) shows that when teachers use the target language in a clear and supported way, students pay attention better and stay motivated.

• When it’s missing: Ms Dupont tried a full French-only lesson without scaffolds. Students stared blankly and whispered “I don’t get it,” and by the end even she felt very frustrated, since the lack of support left them adrift. In my view, scaffolds are what may turn TL use into success rather than confusion… as I have often said in my blogs. Could we really expect teenagers to cope without support when even adults would struggle?

3. Maintain Pace and Flow

• Habit: Rapid transitions, chunked activities (no long dead time), visible countdowns, and planned variety. This has always been my greatest strength. It can be exhausting but it pays enormous dividends. In my lessons the students simply didn’t have the time to misbehave.

• Why it works: Idle time is the enemy of behaviour, since “momentum” reduces chances for distraction.

• Research: Evertson & Emmer (2013) showed that lessons where teachers kept up a steady pace had fewer behaviour issues and students’ focus was stronger.

• When it’s missing: Mr Jones handed out a long reading without clear timing. Students drifted into side-conversations while he fiddled with the projector, and he saw that energy may drain very quickly when pace dips, which convinced him that momentum is as important as content. In my experience, it’s momentum more than anything else that protects behaviour.

4. Give Clear, Short Instructions (in TL or L1 as needed)

• Habit: Brief, step-by-step instructions, often backed with visuals or gestures are gold, especially when you have students with special needs. Instructions needn’t be in the target language, the most important thing is that the task is.

• Why it works: Unclear instructions invite off-task chatter, whereas clarity gets students working faster.

• Research: Ellis (2009) explains that when instructions are clear and broken down, students understand more easily and are less likely to go off task.

• When it’s missing: Ms Ahmed once gave a five-minute grammar lecture before a task, and although she thought she was being thorough, students weren’t sure what to do and copied the wrong exercise. Since then she has found that keeping instructions short and visual works best. In my view, nothing may derail a class faster than muddled instructions!

5. Balance High Expectations with Warmth and Respect

• Habit: Combine firm insistence on participation (“everyone speaks”) with friendly relational warmth, always showing respect for students and their space. Respect here means listening, allowing thinking time, noticing effort, and treating students’ contributions with fairness. If you disrespect a student, you will get disrespect back – often many times over.

• Why it works: Students are much more likely to cooperate when they feel respected and supported. High standards matter, but they only work when learners also feel safe and valued.

• Research: Muijs & Reynolds (2011) show that classrooms where teachers combine warmth with high expectations have fewer discipline problems, and Pianta (1999) adds that respectful teacher–student relationships are central to students’ behaviour and learning.

• When it’s missing: Mr Williams wanted to be “the nice teacher” and didn’t insist on TL answers. Gradually, students stopped trying, and he later saw that warmth without challenge breeds low effort — and that respect without clear boundaries can quickly slip into indulgence. In my experience, the best classes are both strict and friendly, with respect running both ways. Isn’t that what we would want if we were in their shoes? And how would you feel as a student if no one really listened to your answers?

6. Actively Watch the Room

• Habit: Circulate, make eye contact, use proximity, and point out positive behaviour. Nothing worse than a teacher sitting behind the desk for most of the lessons.

• Why it works: “Withitness” (Kounin, 1970) reduces misbehaviour before it builds.

• Research: Kounin (1970) showed that when teachers scan the room often and move around, misbehaviour drops because students know the teacher is aware of students’ actions.

• When it’s missing: Ms Rossi stayed rooted at the front with her laptop, and a group at the back began sharing headphones, so by the time she noticed, focus was gone. In my experience, the teacher who never leaves the front is the one who loses control.

7.Maximise Student Talk, Cut Teacher Talk

• Habit: Structured pair work, sentence-builder scaffolds, choral response, micro-interactions.

• Why it works: Engagement rises when learners feel ownership, and boredom drops when interaction is constant.

• Research: Swain (2000) shows that when students have to produce language regularly, they stay more focused and are less likely to drift off task.

• When it’s missing: Mr O’Connor explained grammar for twenty minutes without pause, and although he felt he was being clear, students switched off and when it was time to speak the energy was flat. In my experience, the more students talk, the less likely it is for behaviour to become an issue.

8.Use Positive Framing and Praise

• Habit: Notice effort (“Very fluent !” – in the case of a student who has managed to speak fluently despite a few mistakes) more often than punishing errors.

• Why it works: Builds much stronger motivation and a culture of effort rather than fear.

• Research : Hattie (2009) found that praise and encouragement have a bigger effect on students’ learning and behaviour than punishment or criticism.

• When it’s missing: Ms Green corrected every mistake bluntly, and although she thought she was helping accuracy, over time volunteers dwindled. Once she switched to praising effort first, students bounced back. In my experience, classrooms thrive when effort is noticed more than errors.

9. Embed Predictable Classroom Signals

• Habit: Consistent cues for silence, transitions, attention (hand signals, countdowns, TL phrases).

• Why it works: Students respond faster when cues are automatic, reducing friction.

• Research : Simonsen et al. (2008) showed that when teachers use the same signals consistently, students follow instructions more quickly and lessons run more smoothly.

• When it’s missing: Mr Chen had no fixed signal — sometimes clapping, sometimes waiting — and students took longer each time to respond, which wasted time and caused frustration. A simple countdown solved it. A predictable signal is worth ten shouted reminders! After all, how can students concentrate if the rules of attention keep changing?

10. Reflect and Adjust Practice

• Habit: Regularly check which activities trigger drift (e.g., too much copying, too open-ended) and change them.

• Why it works: Flexibility prevents repeating the same “behaviour traps.”

• Research: Farrell (2015) argues that teachers who reflect regularly improve classroom control because they see what doesn’t work and adapt it.

• When it’s missing: Ms Lopez set up a free discussion in Spanish, and within minutes it was all in English, which showed her that it needed scaffolds and sentence frames — and next time, it worked. In my experience, reflection is the difference between repeating mistakes and turning them into learning… as I have often said in my blogs.

11. Plan for Smooth Transitions Between Activities

• Habit: Signal changes clearly, prepare materials in advance, and keep movement purposeful.

• Why it works: Transitions are “danger moments” when chatter and off-task behaviour start, so smooth handovers reduce downtime.

• Research : Stronge (2018) shows that teachers who plan transitions carefully waste less time and prevent flare-ups in students’ behaviour.

• When it’s missing: Mr Ahmed handed out worksheets one by one, and the class slowly lost focus, so he decided to prepare resources on desks before the lesson and behaviour stayed very steady.

12. Model the Behaviour and Language You Expect

• Habit: Show enthusiasm for the TL, model politeness, and show how to stay on task. Respect also has to be modelled: when teachers consistently show courtesy and fairness, students copy that behaviour.

• Why it works: Students copy teacher behaviour, and modelling sets the standard without confrontation.

• Research : Bandura (1977) showed that students copy what teachers do, so if we model language and respectful behaviour, students’ responses are likely to follow.

• When it’s missing: Ms Carter told students to use Spanish greetings but never used them herself, and unsurprisingly within days the class had dropped them too. Once she modelled consistently, the routine stuck!

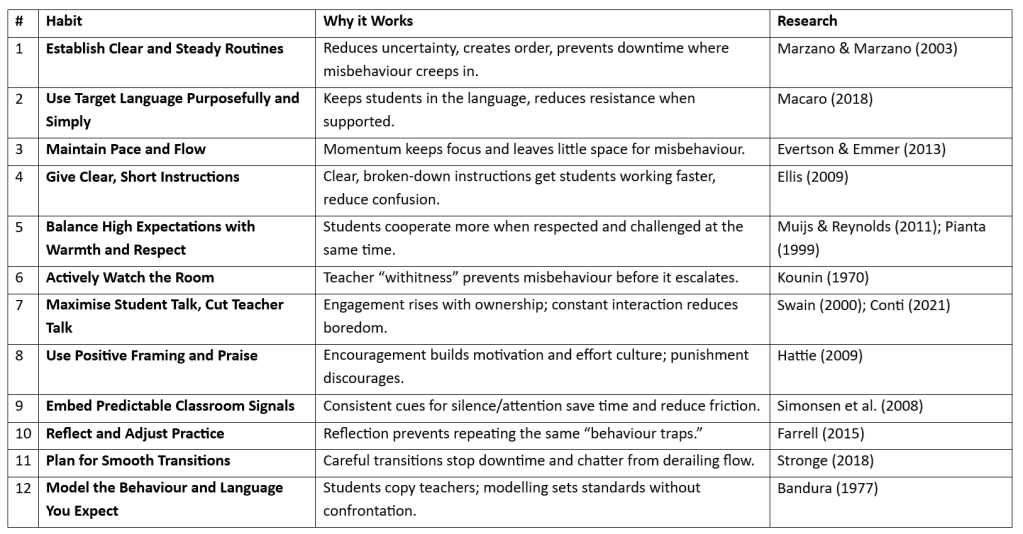

Table 1 – Summary

Conclusion

Effective classroom management in MFL is not about quick fixes or charisma — it is about small, research-backed habits used steadily. In my experience, predictable routines, clear instructions, structured TL use, high pace, smooth transitions and positive reinforcement together can create a purposeful climate where students focus on learning and not on disruption. By building these habits — including showing respect for students and their space, modelling expectations, and planning transitions with care — teachers may discover that they reduce the stress of discipline and free up energy to do what is most important: helping learners build much greater self-efficacy, confidence, fluency, and joy in using the language. And in the end, is this not the real aim of MFL teaching?

References

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Ellis, R. (2009). Task-based language teaching: Sorting out the misunderstandings. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 19(3), 221–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2009.00231.x

- Evertson, C. M., & Emmer, E. T. (2013). Classroom management for elementary teachers (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Farrell, T. S. C. (2015). Reflective language teaching: From research to practice. London: Bloomsbury.

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge.

- Kounin, J. S. (1970). Discipline and group management in classrooms. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Macaro, E. (2018). English medium instruction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Marzano, R. J., & Marzano, J. S. (2003). The key to classroom management. Educational Leadership, 61(1), 6–13.

- Muijs, D., & Reynolds, D. (2011). Effective teaching: Evidence and practice (3rd ed.). London: Sage.

- Pianta, R. C. (1999). Enhancing relationships between children and teachers. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Simonsen, B., Fairbanks, S., Briesch, A., Myers, D., & Sugai, G. (2008). Evidence-based practices in classroom management: Considerations for research to practice. Education and Treatment of Children, 31(3), 351–380.

- Stronge, J. H. (2018). Qualities of effective teachers (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- Swain, M. (2000). The output hypothesis and beyond: Mediating acquisition through collaborative dialogue. In J. P. Lantolf (Ed.), Sociocultural theory and second language learning (pp. 97–114). Oxford: Oxford University Press.