Introduction

I grew up in an educational culture where grammar was sacred! As an Italian learner — and later teacher — grammar was drilled into us like holy scripture: conjugation tables chanted in chorus, endless rule explanations, 100% accuracy being a must, red pen corrections worthy of a bloodbath… When I started teaching, I brought that entire tradition with me to England into the classroom, which, because I was still young and stubborn and quite convinced I was “doing it properly,” made me blind to how little of it actually worked.

I genuinely believed that if I explained things clearly enough, if I corrected enough, if I drilled enough, the grammar would stick forever ! But of course… it didn’t. Not the way I expected, at least. My students memorised beautifully, then promptly forgot. They “knew” the rule but couldn’t use it in real time — which, if I’m honest, made me more frustrated than them.

And here’s the awkward truth: as a young Italian teacher who thought grammar was the sun around which all learning revolved, I clung to practices that looked good but did very little. I built lessons around clarity rather than acquisition, around rules rather than readiness… even when, deep down, I felt something wasn’t working. It took me years — and a painful amount of self-awareness — to realise that much of what felt like “good grammar teaching” was, in fact, a comforting illusion.

So here they are — 12 (nearly) useless things language teachers do when teaching grammar. And I say “they”… but I really mean we. I’ve done every single one of them.

1. Aiming to teach “50% grammar and 50% vocabulary” as if they were ‘equal’ strands

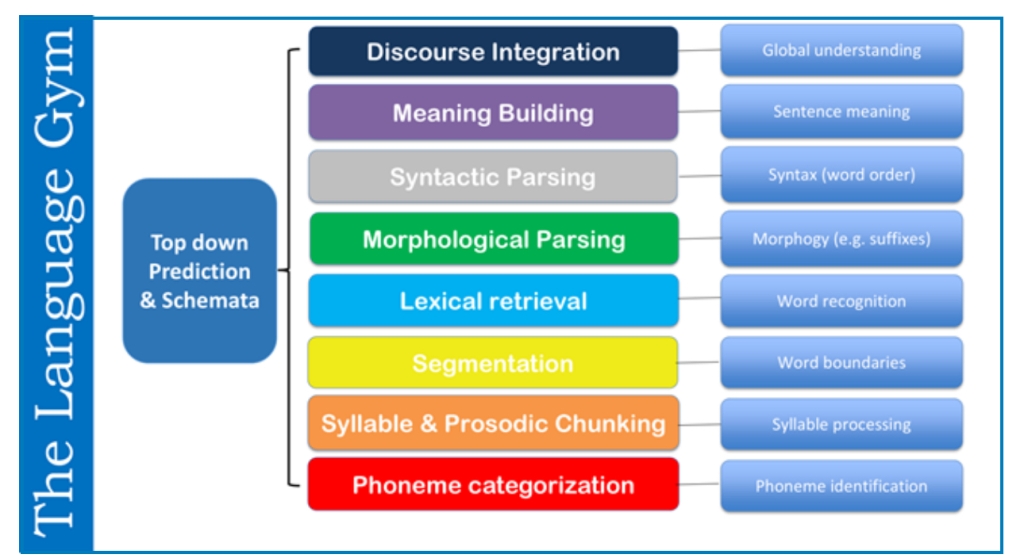

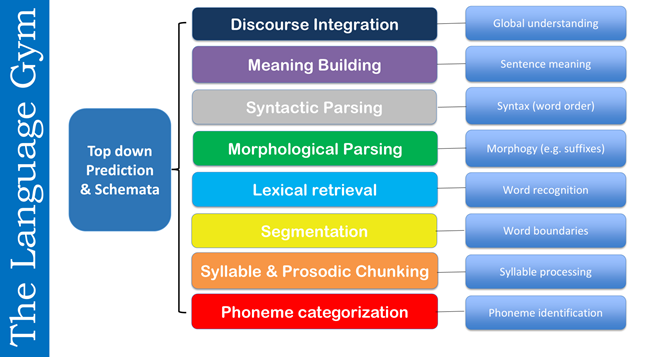

Most teachers I know believe that a balanced curriculum means splitting lesson time between explicit grammar instruction and vocabulary teaching. This approach stems from the traditional “building blocks” view of language: vocabulary supplies meaning, grammar supplies structure. But… if grammar doesn’t develop on command, why do we keep treating it as if it does? Extensive input processing research (e.g. Bill VanPatten; Stephen Krashen) has shown that lexical knowledge drives much of language comprehension and production, while grammar tends to emerge gradually through repeated, meaningful encounters. In my opinion, this is where so many schemes of work go wrong: they treat grammar as if it obeyed the same logic as vocabulary. I remember early in my career, trying to give exactly “half the lesson” to grammar and half to vocabulary… and being puzzled when students learned the words but kept ignoring the structures. And let’s be honest, grammar does not bend so easily to the teacher’s timetable, particularly when the learner’s internal syllabus — that invisible, stubborn system — has its own sequence of what it’s willing to process and when! Unlike vocabulary, grammar cannot be “taught and learned” in neatly packaged units… Overallocating instructional time to grammar assumes learners can proceduralise rules through exposure to explanation alone — which they can’t!

Why it feels good: It gives lessons a neat structure and a sense of control.

Why it’s useless: Grammar doesn’t behave like vocabulary — it resists timetabling.

Modest benefit: Helps keep teachers aware of “balance,” though the balance itself is illusory.

2. Starting with a “clear explanation” of the rule

Correct me if I am wrong, but beginning a grammar lesson with an explicit explanation is still one of the most widespread practices in language classrooms! It stems from the belief that a well-sequenced deductive explanation lays the foundation for later practice. I still recall a lesson where I gave what I thought was the most lucid explanation of the subjunctive I had ever produced… my students nodded, smiled, repeated after me — and then, in the next activity, cheerfully ignored everything I had just explained. Have you ever had that moment — when you’re speaking with absolute clarity, and the class is nodding like a choir — and yet nothing sticks? In my opinion, this happens because explanations without prior exposure are like arrows shot into fog: technically straight, but never landing where you need them. According to Bill VanPatten and Rod Ellis, learners must first build a mental representation of a structure through meaningful input before explicit rules can support noticing or refinement. And truly, as any good maestro would say, a rule explained too soon is a rule wasted… especially when the learner — bewildered but polite — nods along while their brain files the explanation under “maybe later.”

Why it feels good: Teachers feel clear, structured, professional.

Why it’s useless: Without mental representation, the explanation floats away.

Modest benefit: Might support later noticing if the input foundation is strong.

3. Relying on form-focused drills as the main grammar practice

Form-focused drills—such as conjugation runs, substitution exercises, or transformation tasks—are seductive because they look rigorous and keep classrooms orderly! I used to run those tidy, military-style conjugation drills… everyone in unison, every verb ending perfectly shouted out… and yet, when it came to spontaneous speaking, the endings dissolved like sugar in hot coffee. In my opinion, drills give teachers a comforting illusion of progress precisely because they’re measurable and neat, not because they’re effective. Research (e.g. Michael Long, Nina Spada, Roy Lyster) shows that mechanical manipulation tends to remain in declarative memory. It is a bit like rehearsing a dance step alone in front of the mirror — elegant perhaps, but never quite the real thing, especially when the music, the partner, and the unpredictable rhythm of actual communication are missing entirely. Drills can support familiarisation, but they don’t develop implicit knowledge on their own.

Why it feels good: Neat, measurable, controlled practice.

Why it’s useless: Doesn’t transfer to spontaneous language use.

Modest benefit: Can build familiarity with forms if used sparingly.

4. Re-explaining the rule every time students make a mistake

This is one of the most deeply ingrained teacher habits! Many assume that if students continue to make errors, it must be because they’ve forgotten the rule. I can still picture myself, twenty years ago, circling like a hawk around one poor Year 10 class… re-explaining the same structure for weeks… convinced that if only I said it better this time, they’d finally get it. But how many times can you explain the same thing before realising the problem lies elsewhere? Personally, I believe this ritual of re-explaining is more about calming our own anxiety as teachers than helping students actually acquire the structure. Research in interlanguage development (e.g. Tracy Terrell, Bill VanPatten, Shawn Loewen) shows that most errors are developmental rather than due to ignorance. To insist too much here is like explaining pasta recipes to someone who’s never boiled water — it simply won’t work, because until they have felt the bubbling pot and the weight of the pasta softening, the words remain just that: words. Re-explaining the rule rarely leads to restructuring; learners nod in recognition but their interlanguage remains unchanged!

Why it feels good: Feels patient and thorough.

Why it’s useless: Re-explaining rarely leads to restructuring.

Modest benefit: Can reassure anxious learners — but that’s all.

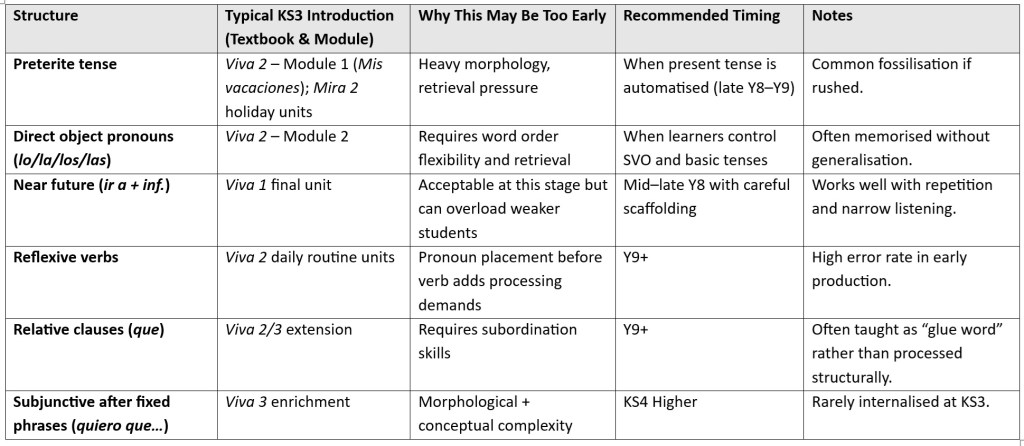

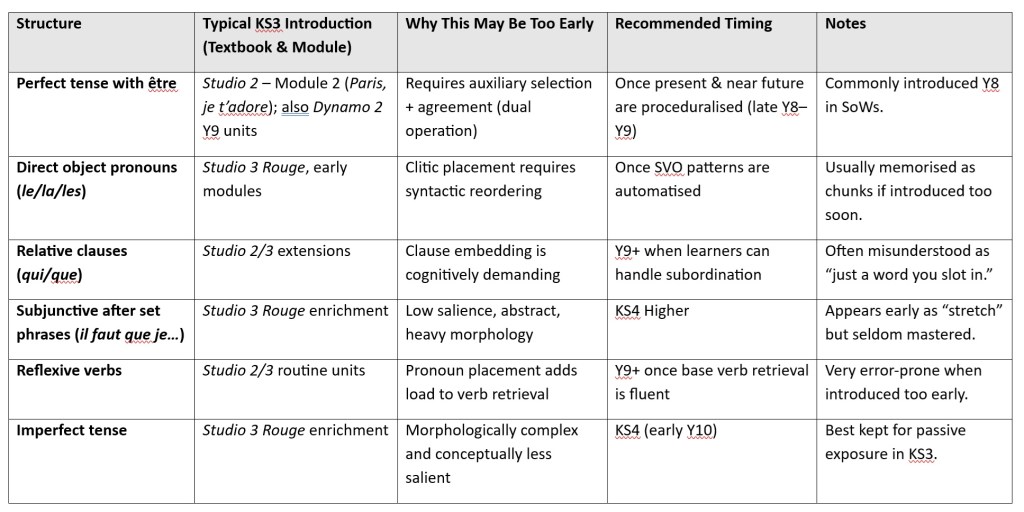

5. Teaching grammar points simply because they’re next in the textbook

Textbook pacing and syllabus structure often dictate grammar sequencing rather than psycholinguistic readiness! I remember marching into a lesson one October with full enthusiasm… ready to teach the conditional tense to students who could barely produce il y a without mangling it. It was like trying to hang a chandelier in a house without walls. In my opinion, this is one of the most dangerous habits in language teaching: letting the book decide what learners are ready for. Studies on teachability (e.g. Manfred Pienemann) demonstrate that learners can only internalise certain structures once their interlanguage has reached the appropriate developmental stage. Ah, but here lies the classic tragedy: the book marches on… but the learner does not follow… and the teacher — caught between pacing and patience — often knows, deep down, that the grammar has slid off their students like water off marble. Why do we persist in following the book as if it knew the students better than we do?

Why it feels good: It keeps you on schedule and “aligned” with the curriculum.

Why it’s useless: Readiness isn’t dictated by pacing guides.

Modest benefit: Ensures coverage… but not acquisition.

6. Using isolated translation sentences to ‘check mastery’

Translation has long been used as a proxy for grammatical understanding! I used to assign long lists of translation sentences for homework… very traditional, very proper… and then wonder why, during oral work, those same structures evaporated from their minds like mist. In my opinion, translation is the educational equivalent of teaching someone to ride a bike indoors on a stationary trainer: neat, safe, but utterly disconnected from the real road. If translation worked so well, why was their spoken grammar still full of holes? Decades of research (e.g. Stephen Krashen, Rod Ellis) have shown that explicit, controlled production does not equate to procedural ability. Translation may reveal explicit knowledge, but it does not foster automatisation, particularly under communicative pressure! And let’s face it, no one ever became fluent by translating sentence after sentence in splendid isolation… as if the language were an obedient little puzzle rather than a living, breathing system.

Why it feels good: It looks rigorous, academic, “serious.”

Why it’s useless: Tests explicit knowledge, not proceduralised use.

Modest benefit: May reveal gaps — but doesn’t fix them.

7. Turning grammar into a polished PowerPoint performance

The well-designed grammar presentation is seductive because it looks “professional”! I’ve spent hours polishing slides… adding colour-coded timelines and cute arrows… only to realise later that the only thing students remembered was the animation. Isn’t it funny how the more beautiful the slides, the less they seem to learn? Personally, I think this reflects our obsession with control and clarity more than any real evidence of what helps acquisition. Research on input processing (e.g. Bill VanPatten, Teresa Cadierno) repeatedly shows that even the clearest presentation has little impact on acquisition if it’s not anchored in meaningful, repeated input. It is, as one might say, like serving a beautiful plate with nothing on it — the form without the substance, the music without the notes, the speech without the heartbeat. Learners may understand at the surface level, but they don’t retain or proceduralise!

Why it feels good: Looks polished and authoritative.

Why it’s useless: Presentation ≠ acquisition.

Modest benefit: May aid clarity if tied to rich input.

8. Using grammar quizzes and tests as proof of learning

Assessment practices often reflect institutional priorities more than learning realities! I’ve had entire departments celebrate good grammar quiz results… myself included… only to be brought down to earth the moment those same students tried to speak spontaneously. In my opinion, grammar quizzes are one of the great comfort blankets of language teaching: they give us something easy to measure, not something meaningful to trust. Studies (e.g. Norris and Ortega, Shawn Loewen) show that traditional grammar tests mostly tap explicit declarative knowledge. They produce neat data but don’t reveal whether learners can use grammar spontaneously in real time! And what good is a neat number on a spreadsheet if, the moment a student must actually speak, the carefully “learned” structure vanishes like steam from a pot left unattended on the stove? What use is a neat score when the grammar crumbles in the heat of real communication?

Why it feels good: Gives tangible, trackable results.

Why it’s useless: Measures short-term recall, not competence.

Modest benefit: Helps identify what students can recall — briefly.

9. Rewarding grammatical accuracy over processing and fluency

Accuracy-based grading schemes prioritise error-free production over communicative competence! I used to mark with the merciless red pen of a grammar purist… every error circled, every deviation noted… and then wonder why students spoke less and less each term. Isn’t it ironic how the more we correct, the less they speak? To me, this obsession with accuracy reflects a deep cultural inheritance in language teaching — one that values form over flow. Research on fluency and output (e.g. Merrill Swain, Bill VanPatten) shows that overemphasis on correctness encourages monitoring and risk avoidance. Learners produce less, rely on safe language, and develop fossilised habits! And in this way, what begins as a noble quest for precision slowly becomes a slow suffocation of expression, as if every note in the music had to be perfect before the orchestra was even allowed to play.

Why it feels good: Feels rigorous, high standards, academic.

Why it’s useless: Encourages monitoring, not communication.

Modest benefit: Can raise awareness of accuracy — if not overdone.

10. Relying on grammar-based recasts during conversation practice as the main feedback strategy

Recasts—implicit reformulations of errors—have received considerable attention in SLA research! I once spent weeks conscientiously reformulating every student error during pair work… convinced I was gently shaping their language… until I realised, watching them, that they weren’t even registering half of it. In my opinion, this is one of those strategies that survives not because it works, but because it feels good to the teacher. If they don’t even notice, who exactly are we correcting? Studies (e.g. Roy Lyster, Alison Mackey, Shawn Loewen) reveal that learners frequently fail to notice recasts, especially for low-salience grammatical features. Even when noticed, recasts rarely trigger long-term restructuring unless enhanced (through stress, repetition, or salience). It is like whispering to the wind and hoping it changes direction — a lovely gesture perhaps, but one that rarely moves anything but the whisperer’s own lips. They are far less effective for grammar than for pronunciation! Yet teachers love them because they feel natural and non-intrusive!

Why it feels good: Feels gentle, natural, communicative.

Why it’s useless: Often unnoticed, rarely leads to durable change.

Modest benefit: Can support pronunciation or high-salience forms.

11. Correcting everything: the ‘all-out correction’ fallacy

Many teachers still believe that correcting every single grammatical error during oral production is the most effective way to build accuracy! I can still see the look on my students’ faces years ago… when I stopped them mid-sentence again and again… the spark went out of their speech as surely as air from a punctured tyre. Personally, I think this habit says more about our discomfort with errors than about their pedagogical value. Research on corrective feedback (e.g. Roy Lyster, Shawn Loewen) has consistently shown that excessive correction overwhelms learners, disrupts fluency, and often fails to lead to uptake. And truly, too much correction is like seasoning a dish with the entire salt cellar — unbearable and useless — but worse still when the learner, trying to speak, is interrupted so often that the sentence withers before it’s even born. When every slip is corrected, students focus on monitoring rather than communicating, leading to increased anxiety and reduced output! Do we honestly believe that a wall of correction can build confidence?

- Why it feels good: Creates the illusion of control and rigour.

- Why it’s useless: Overwhelms learners, kills fluency.

- Modest benefit: Works in selective, focused form — not all-out.

12. Believing that everyone can “do grammar”

This, in my opinion, is one of the most seductive illusions in language teaching: the idea that, with enough explanation, practice and feedback, every learner can process grammar the same way! I used to stand there with my conjugation charts and my crystal-clear explanations, honestly convinced that clarity was the great leveller… until I noticed how some students thrived while others — intelligent, engaged, capable — stared back with quiet panic in their eyes. Decades of research (e.g. Peter Skehan, Richard Schmidt) show that grammar instruction interacts strongly with individual differences in aptitude, working memory and cognitive style. Not everyone can hold a rule in their head, process it consciously and use it spontaneously. Some can. Many can’t. And what’s more… they don’t have to. Plenty of successful language learners have never “done grammar” in this way — they’ve simply acquired it through patterned, meaningful exposure. Pretending otherwise creates frustration, shame, and a classroom hierarchy where the “grammar kids” shine and others quietly withdraw. How many brilliant learners have we lost to this quiet, invisible divide?

Why it feels good: Suggests that “good teaching” works for everyone.

Why it’s useless: Learners vary greatly in aptitude and processing capacity.

Modest benefit: Encourages some to engage with rules — but not all can or should.

Conclusion

When I look back at my early years in the classroom, I see a young Italian teacher armed with rules, drills, grammar tables, and unwavering faith in explanation. I thought precision was everything… and communicative reality was something that came after. But language doesn’t work that way — and neither do learners.

These “nearly useless” practices aren’t malicious. They persist because they look like teaching. They make us feel in control. But control isn’t acquisition. Real learning happens in the messy, implicit, input-driven, developmentally timed space where rules don’t always behave.

And so, with a mix of affection and irony, I can say: I was my own worst example. And that’s why I know these habits so well.

You must be logged in to post a comment.