Introduction

Listening is not a passive skill. It is the most cognitively demanding of all receptive modes and, paradoxically, the least explicitly taught. In the Extensive Processing Instruction (EPI) framework, Listening as Modelling is the engine that drives grammar and lexicon acquisition. It provides the brain with exemplars — auditory models — from which learners infer patterns, internalise sound-meaning mappings, and ultimately develop procedural fluency.

Below I outline ten principles, ranked in order of importance, for designing listening input that does precisely that: not merely test comprehension, but model the language system.

1. Repeatability of input

By repeatability, I don’t simply mean that the audio should be played multiple times (see point 9 for this). I mean that learners must be able to repeat what they hear — at least in their heads. In other words, for listening to lead to learning, the input must be mentally rehearseable. This hardly ever happens with standard textbook recordings, which are typically delivered too fast, too dense, and too prosodically complex for beginners to internalise. Yet, if learners cannot replay a phrase mentally — if the acoustic trace fades before they can process it — no real learning can occur.

Research on working memory and the phonological loop (Baddeley 2003; Vandergrift & Goh 2012) confirms that learners need time and manageable input to build stable sound–form representations.

Similarly, Kadota’s (2019) shadowing studies show that subvocal rehearsal (“inner repetition”) strengthens the connection between auditory perception and articulatory memory — a key precursor to oral fluency.

Segalowitz (2010) likewise found that mental rehearsal promotes automaticity by reducing reaction time in lexical retrieval.

That’s why, in EPI, listening materials are slowed down slightly, chunked clearly, and delivered with natural but accessible prosody. The goal is to make every utterance repeatable in the mind’s ear, so that learners can shadow, rehearse, and gradually consolidate what they hear into long-term memory.

2. Comprehensibility

Listening as modelling presupposes that the input is 95–98 % comprehensible (Nation 2014).

Below this threshold, working memory is overwhelmed and attention shifts from pattern detection to survival decoding.

Comprehensible input (Krashen 1985) still holds true here, but not as passive exposure — rather, as carefully scaffolded auditory material that allows the learner to perceive grammar in action.

In EPI, we achieve this through rich visual context, pre-teaching of key lexis, and cumulative recycling.

Only when meaning is secure can attention move to form (VanPatten 1996).

Field (2008) and Vandergrift & Goh (2012) both note that comprehension is the entry point for awareness: once meaning is predictable, learners can start noticing the fine phonetic or morphological detail.

If the learner’s brain is too busy decoding, it cannot engage in grammatical hypothesis formation.

3. Input flood

If the aim is to model a linguistic feature, that feature must occur frequently. A single instance of the perfect tense does not enable abstraction; dozens do. Ellis (2002) refers to this as frequency-driven implicit learning: learners infer form–function mappings statistically. In cognitive terms, the learner’s brain needs repeated co-occurrence between meaning and form to establish reliable probabilistic patterns (Bybee 2006).

Hence, the listening text should be an input flood — dense with the target structure but still natural.

For example, to model reflexives, one might use a short monologue containing multiple je me lève / je me prépare / je me couche instances. Repetition creates the conditions for unconscious rule formation.

4. Practice across all micro-skills of listening

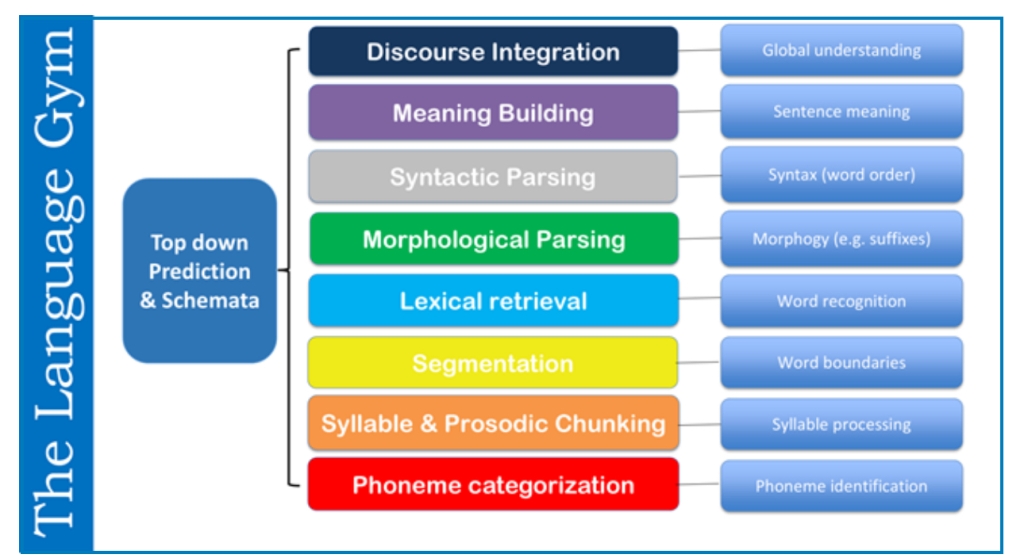

Listening competence depends on a finely layered hierarchy of micro-skills — each contributing a distinct cognitive operation to comprehension. These operate simultaneously and interact dynamically, from bottom-up decoding (sound to meaning) to top-down prediction (context-driven inference).

The figure below (The Language Gym, © Conti 2025) illustrates these interconnected levels:

At the lowest tier lie phoneme categorisation and identification, essential for distinguishing minimal contrasts and stabilising L2 phoneme boundaries (e.g., beau vs bon, pero vs perro). Above this sit syllable and prosodic chunking, through which learners perceive rhythm, stress, and intonation patterns — the “music” of speech that signals grammatical and pragmatic boundaries (Field 2008). Next comes segmentation, the ability to infer word boundaries in continuous speech, one of the hardest perceptual skills for beginners (Cutler & Norris 1988).

Once segments are recognised, lexical retrieval allows the brain to map sound to known word forms rapidly (Segalowitz 2010), while morphological parsing enables the listener to extract grammatical information from endings or prefixes (-ais, -ons, -ment). Syntactic parsing then assembles these decoded items into an organised sentence structure, enabling propositional meaning to emerge.

At higher levels, meaning building integrates lexical and syntactic cues into coherent sentence-level understanding, while discourse integration extends comprehension across utterances, managing anaphora, coherence, and topic flow. Finally, overarching all levels is top-down prediction and schemata activation (Anderson & Lynch 1988; Vandergrift & Goh 2012): the listener’s use of prior knowledge and contextual cues to anticipate meaning.

Training these skills explicitly — from phoneme awareness up to discourse coherence — transforms listening from a purely receptive act into a deliberate cognitive apprenticeship. Each sub-skill must be nurtured systematically in EPI through highly patterned, repeatable input that strengthens automaticity across the processing chain.

5. Highly patterned input

Patterning reduces cognitive load and magnifies predictability. As Goh (2000) observed, predictable prosodic and syntactic patterns help beginners allocate attention to variable elements (e.g. verb endings) rather than re-decoding sentence structure every time. For weaker learners, patterned listening might involve recurring frames such as

Je vais au cinéma / Tu vas au supermarché / Il va à l’école / Nous allons à la piscine.

Once the skeleton is known, the brain can focus on the change — the noun, the verb form, or the preposition — thereby supporting noticing of contrast (Schmidt 1990). Leow (2015) and DeKeyser (2017) both show that pattern-based repetition fosters proceduralisation by creating automatic parsing routines.

In the EPI approach, this principle underpins Narrow Listening, a technique where learners hear several near-identical texts differing only in 10–12 micro-details such as times, places, or subjects.

For instance, one speaker might say “Je me lève à sept heures” while another says “Je me lève à huit heures”. This slight variability within a highly stable frame allows learners to anticipate structure, detect meaningful contrasts, and internalise morpho-syntactic regularities with minimal cognitive strain.

The predictability of the scaffold facilitates pattern recognition, while the changing elements promote semantic differentiation — a dual process supported by research on input variability and implicit abstraction (Ellis & Ferreira-Junior 2009; Spada & Tomita 2010). In short, Narrow Listening à la Conti turns auditory input into a finely tuned laboratory for implicit grammar learning.

6. Thorough processing

Listening tasks must elicit deep semantic and syntactic engagement, not just recognition of key words. Field (2008) distinguishes between text-driven comprehension (surface) and form-driven processing (analytic). Both are essential, but only the latter produces durable change.

By “thorough processing,” I mean detailed processing of the text, not merely the gist. In other words, learners should not only understand what is said but also attend to how it is said — at the level of morphology, syntax, and meaning relationships.

Activities such as faulty translation, spot the intruder, spot the missing detail, sentence puzzle, faulty transcript / spot the nonsense, and dictations (including gapped or narrow variants) compel learners to focus on the smallest form–meaning correspondences. These tasks ensure that every morpheme, lexical nuance, or grammatical marker is consciously processed.

This contrasts sharply with the partial processing typically elicited by textbook comprehension questions (e.g., multiple choice, true/false, gist-based tasks). Such tasks promote top-down inference and selective attention, not bottom-up accuracy. Learners extract just enough semantic information to answer, leaving vast portions of the input unanalysed.

As Field (2019) and Vandergrift & Goh (2012) point out, comprehension-based listening often leads to what they call “good enough processing” — the brain’s tendency to settle for approximate understanding rather than full parsing.

In this sense, standard listening comprehension is diagnostic, not instructional. It measures what learners can already understand, rather than improving their parsing skill or phonological awareness. By contrast, thorough processing tasks disrupt this comfort zone. They push learners into analytic listening, where meaning must be verified at the micro-level. This aligns with the Levels of Processing Hypothesis (Craik & Lockhart 1972): the deeper the semantic and syntactic engagement, the stronger and more durable the memory trace. Boers (2013) further notes that such semantic elaboration leads to double the retention rate compared to surface comprehension.

In EPI, therefore, “thorough processing” means deliberately engineering listening activities that force the learner to process the input in depth — decoding, analysing, and verifying it step by step. The result is not just understanding, but awareness through comprehension — the foundation of procedural grammar learning.

7. Repeated processing

Processing the same input in different ways multiplies the learning payoff. Rost (2011) calls this multi-pass listening: each pass adds a new purpose — gist, detail, inferencing, noticing of form, then reproduction. Each repetition consolidates mapping between sound, structure, and meaning — the triad at the heart of proceduralisation. Ellis & Shintani (2014) note that varied retrieval is more effective than mechanical repetition; each new processing task forces deeper encoding.

This is where EPI’s MARSEARS sequence (Modelling, Awareness, Receptive Processing, Structured Production, etc.) operationalises listening as a cyclical, ever-deepening process rather than a one-off comprehension exercise.

8. Chunking

Fluent listening depends on recognising multi-word units (Pawley & Syder 1983). Beginners, however, tend to process word by word, overloading short-term memory (Baddeley 2003). By training learners to perceive formulaic sequences — je voudrais un café, no me gusta nada, tengo que estudiar — we lighten the processing load. Shadowing, echo repetition, and rhythmic chanting help store these as single phonological items. Once chunks are automatised, syntactic parsing accelerates and comprehension becomes near-instantaneous.

Boers (2021) and Ellis (2016) confirm that formulaic sequences are the fastest route to fluency because they reduce grammatical computation in real time. In EPI, listening texts are deliberately chunk-heavy: lexical bundles are recycled across sessions until retrieval is automatic, forming the auditory basis for later spontaneous speech.

9. Input enhancement

Attention is selective; learners won’t notice grammar unless something draws their focus. Input enhancement (Sharwood Smith 1993) involves manipulating acoustic or visual salience to highlight target forms: slowing down, stressing endings, or colour-coding transcripts. Field (2019) warns against artificial exaggeration, but moderate enhancement helps learners form accurate phonological representations of new morphology. For example, lengthening -ed in English past tense or emphasising -ons in nous mangeons allows perception to precede production. Saito (2019) shows that such enhancement can speed up the acquisition of phonological categories for L2 learners.

In the EPI classroom, enhancement is often achieved not by artificial stretching but by teacher-led acoustic tuning — conscious, intelligible speech that models prosody without distortion.

This makes the grammar audible without making it unnatural.

10. Task essentialness

Finally, learners must need to process the target feature to complete the task successfully. VanPatten (1996) calls this processing instruction: ensuring that meaning cannot be derived without attending to form. If students can answer by recognising one word, the modelling opportunity is lost. But if success depends on perceiving a morphological cue — tense, number, or gender — attention will be naturally drawn to it. Lee & VanPatten (2003) and Marsden (2006) show that task essentialness drives deeper form-meaning mapping than explicit rule explanation ever could.

Within EPI, this principle ensures that the communicative intent of listening tasks always rests upon understanding the grammar embedded in the input. In other words, listening becomes learning only when the grammar matters for meaning.

Putting it all together

An effective Listening as Modelling lesson follows a coherent sequence built around all ten principles:

- Repeatability of input – begin with input learners can mentally rehearse (inner repetition/subvocal echo).

- Comprehensibility – keep the text at ~95–98% known so working memory can notice form.

- Input flood – saturate the text with the target feature to support frequency-driven learning.

- Highly patterned input – use stable frames (including Narrow Listening à la Conti, i.e., near-identical texts with 10–12 micro-changes) to reduce cognitive load and highlight contrasts.

- Practice across all micro-skills – deliberately exercise the full hierarchy (phoneme categorisation → syllable/prosody → segmentation → lexical retrieval → morphological parsing → syntactic parsing → meaning building → discourse integration, supported by top-down prediction/schemata).

- Thorough processing – require detailed analysis beyond gist (see section above).

- Repeated processing – cycle through multi-pass purposes (gist, detail, inferencing, noticing, reproduction).

- Chunking – foreground and recycle formulaic sequences to lighten processing and boost fluency.

- Input enhancement – make the target form perceptually salient without distorting natural prosody.

- Task essentialness – design success criteria that depend on perceiving the target feature.

When all ten operate in concert, listening ceases to be a comprehension test and becomes the principal means of grammatical acquisition; the classroom turns into an acoustic laboratory where learners repeatedly experience language as both a model and a mirror of their emerging competence.

IF YOU WANT TO FIND OUT MORE, DO ATTEND MY ONLINE COURSES ORGANIZED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF BATH SPA, HERE: http://www.networkforlearning.org.uk