If you’ve been teaching languages long enough, you’ll know the scene. You spend a whole week hammering a grammar point. You explain it clearly. They nod enthusiastically. You set up the practice. They ace it. And then — the next day — it’s vanished into thin air. Why?! It’s not bad teaching. It’s just how the brain actually learns grammar.

Over the past 30 years, psycholinguists and cognitive scientists have unearthed findings that quietly blow up much of what we used to take for granted about grammar teaching. What follows are ten of the most counter-intuitive, game-changing insights I’ve come across — ordered from the most jaw-dropping to the more familiar. Think of them less as rules to follow and more as truths to wrestle with!

1. Grammar is not a knowledge problem — it’s a perception problem!

And here’s the kicker: a large share of grammar errors aren’t about students not knowing the rule. They’re about students not even hearing what they’re supposed to be learning in the first place (Field 2019; Cutler 2021). If you can’t perceive the plural ending in ils mangent because it’s acoustically weak, then no amount of rule teaching will help. You’re building a castle on sand!

In my experience, this is the real invisible elephant in the room. Learners can’t master what their ears never caught. Imagine trying to master German case endings if half of them were whispered into a pillow. Of course you’d miss them. So do they!

Example: A learner who’s only ever heard fast native speech processes “ils mangent” as “il mange”. The plural marker simply never made it in.

Implication: Grammar teaching has to start with the ear, not the rulebook. Slower speech, clearer prosody, exaggerated patterns, looping input — all those unfashionable things — give the structure a fighting chance of being noticed. Make the grammar audible before you expect it to be learnable!

2. Grammar learning keeps happening long after “mastery” — why?!

Here’s something we rarely admit out loud: mastery is a mirage. Interlanguage research shows grammar knowledge is constantly being quietly restructured beneath the surface (McLaughlin 1990; Ellis 2016; Ortega 2020). What looks stable is often just a plateau — temporary, fragile, waiting for new input to push it somewhere else!

I’ve seen this so many times. A structure that students get “wrong” for months suddenly clicks… not because of my genius as a teacher, but because their brains finally reorganised behind the scenes.

Example: For weeks a student says “J’ai allé”. Then one day, without explicit correction, it becomes “Je suis allé”. What happened? The input environment changed. The system self-corrected.

Implication: Forget about “covering” grammar. In my experience, the structures you think are “done” are just hibernating. Bring them back. Recycle them. Spiral them. That’s how mastery actually happens!

3. Grammar learning is 80 % forgetting and relearning!

We don’t talk about this enough. Grammar acquisition isn’t a straight line. It’s more like a wobbly staircase — you climb, you slide, you climb again! Longitudinal research (DeKeyser 2017; Suzuki 2021) shows learners lose and regain the same grammar over and over again.

I’ll never forget watching a group of Year 8s who’d “lost” voy a ir over the summer and then, two weeks later, picked it up again like an old friend. That wasn’t failure. It was the brain doing its pruning and strengthening work!

Example: A Spanish learner nails “voy a ir” in June, forgets it after the break, and recovers it after two narrow listening cycles in September — this time more solidly.

Implication: Recycling isn’t a nice extra. It’s the backbone of real acquisition. In my experience, planned forgetting — followed by smart reactivation — works better than the most elegant one-off explanation!

4. Grammar errors are often memory failures, not rule gaps!

Let’s not kid ourselves. Many so-called “errors” happen because students’ brains are just too busy! Under cognitive load, low-salience grammar gets chucked out of working memory like excess luggage (Ellis & Roehr-Brackin 2018; McDonough 2019).

You’ve seen it: students get everything right in controlled practice… and then it falls apart in spontaneous speech. Why? Not ignorance. Overload!

Example: A learner confidently says “Elle a mangé hier” in a drill but under time pressure blurts out “Elle manger hier”. The tense didn’t vanish. It just didn’t make the cut in the moment.

Implication: Build fluency and retrieval before you expect accuracy under pressure. Otherwise, you’re setting them up to fail — and then blaming them for it!

5. You can’t skip developmental stages!

We’ve all tried it: teaching a structure “early” because the textbook says so. And it flops! Pienemann’s Processability Theory (1998) explains why. The brain follows a predictable developmental sequence. You can prime a structure early, but you can’t make the brain process what it’s not yet ready for (Lightbown & Spada 2021).

Example: Try teaching je le vois to Year 7. Good luck. Come back when they’ve automatised simpler SVO patterns, and suddenly pronouns seem “easy.”

Implication: Teach grammar when it’s teachable. Why bash your head against a wall when the timing is the real issue?!

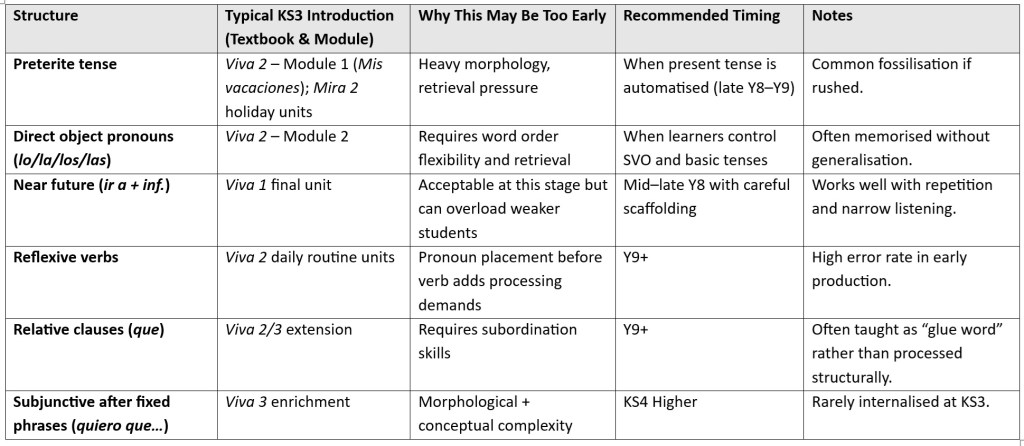

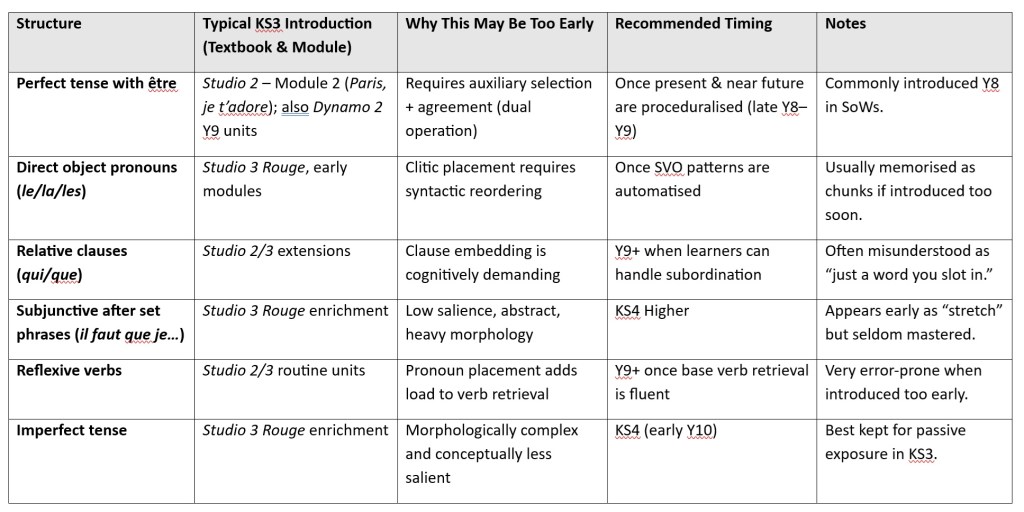

Here are some French and Spanish grammar structures that are commonly taught prematurely, when the students are not developmentally ready:

Tables 1 & 2: Spanish and French structures commonly taught prematurely

6. The brain filters out grammar it can’t yet process!

Even when the structure is “technically audible,” the brain sometimes just doesn’t care! VanPatten’s Primacy of Meaning Principle (1990) shows learners focus on getting the gist, not the form. If they can understand the message without attending to the grammar — they will. Every time!

Example: In “Mes amis sont partis hier”, a beginner might only process mes amis…hier. The auxiliary and participle simply vanish into background noise.

Implication: “Authentic speed” isn’t authentic learning! Comprehensible, chunked, repeatable input makes the grammatical form unavoidable. And when it’s unavoidable, it finally sticks!

7. Feedback works — but only when it’s narrow and repeated!

You know the type of correction that vanishes into the ether? The scattergun kind. The kind where everything is corrected, so nothing is learned. Research tells us feedback does work — but only if it’s tight, consistent, and relentlessly focused on one target (Lyster & Saito 2010; Li 2020).

Example: Correcting ils mange to ils mangent every time, and then reinforcing it through dictations and listening work, gets results. Correcting twenty things at once gets… nothing!

Implication: Feedback isn’t a magic bullet. It’s a drip feed!

8. Grammar is stored as patterns, not rules!

Here’s a truth teachers often feel in their bones: learners don’t think in rules. They think in chunks! Usage-based linguistics confirms it (Bybee 2006; Ellis 2016). They don’t “apply” grammar. They retrieve patterns they’ve heard a hundred times.

Example: Students use “j’ai fini”, “j’ai mangé”, and “j’ai bu” perfectly… but ask them to explain why and they look at you blankly. And honestly? That’s fine!

Implication: The best grammar teaching isn’t about clever explanations. It’s about flooding the mind with patterns so they can be retrieved at will.

9. Narrow, repetitive input beats broad coverage!

Variety is seductive. But the brain loves predictability! Narrow listening (Ellis & Ferreira-Junior 2009; DeKeyser 2017) gives learners the same structure in slightly different guises again and again until it’s carved into their procedural memory.

Example: “Je me lève à sept heures / huit heures / neuf heures.” Ten times. Different speakers. Slight variations. The brain gets the point. Ten random dialogues? Not so much!

Implication: Fluency grows in pattern density, not topic variety. Less glitter, more grooves!

10. Adults can still learn grammar implicitly!

No, it’s not too late! The idea that implicit learning dies after childhood is just wrong (Reber 1993; Williams 2005; Godfroid 2020). Adults still absorb grammar implicitly — it just takes more exposure and a bit of clever design.

Example: Adults hearing “j’ai fini” often enough in comprehensible, repeated listening tasks start using it correctly without ever touching a conjugation chart.

Implication: Don’t underestimate what rich, well-designed input can do. Explicit explanation has its place, but implicit uptake is the engine that drives long-term grammar growth!

11. How long it really takes to master grammar?

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: it takes far, far longer to proceduralise a structure than to recognise it. Research on skill acquisition (DeKeyser 2017; Nation 2022; Anderson 1983) makes it clear: filling in a gap-fill correctly is a beginning, not an end.

Why? Because grammar knowledge must travel from declarative (rule-based, conscious) to procedural (automatic, spontaneous) memory. That leap isn’t small — it’s huge. In my experience, teachers routinely underestimate the time gap by a factor of ten!

| Level of Mastery | Description | Estimated Hours of Focused Practice per Structure | Typical Classroom Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Declarative mastery | Learners can recognise and apply a rule correctly in gap-fills, multiple choice, or written drills when prompted and unhurried. They rely on explicit knowledge and metalinguistic recall. | 4–8 hours of focused exposure and practice (≈ 200–300 meaningful encounters) | Correct answers in written tasks, but errors or hesitation in spontaneous speech. |

| Procedural mastery | Learners can retrieve and deploy the structure automatically in unplanned oral communication, under time pressure and while attending to meaning. Grammar is retrieved intuitively, not consciously. | 40–100 hours of spaced, varied, meaningful encounters (≈ 2,000–3,000 processing cycles) | Consistent, fluent, accurate use in natural speech and writing; flexible use in unfamiliar contexts (e.g., GCSE oral improvisation). |

To put it bluntly: the gap between exercise fluency and exam spontaneity is enormous! A student who can fill in ils mangent correctly after a week of practice is nowhere near being able to say it fluently and automatically in real conversation.

This is why EPI places such a premium on structured recycling, narrow listening, and high-frequency encounters: they’re not extras — they’re the path to proceduralisation. Grammar needs thousands of retrievals before it becomes reflexive. There are no shortcuts!

Conclusions

- Grammar failure often begins in the ear, not in the rulebook!

- What looks like stability is often a plateau hiding restructuring!

- Forgetting isn’t a bug — it’s a feature!

- Memory, perception, and developmental readiness trump explicit rules!

- Patterned exposure and repeated retrieval are the real accelerators!

- Adults can still learn grammar implicitly — if we give them the right input!

- And most importantly… true mastery takes time. Much more time than we’ve been led to believe.

For teachers, this means ditching the fantasy that grammar can be delivered. Instead, we need to engineer the conditions for it to be absorbed!

IF YOU WANT TO FIND OUT MORE, DO ATTEND MY ONLINE COURSES ORGANIZED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF BATH SPA, HERE: http://www.networkforlearning.org.uk

Références

- John R. Anderson. (1983). The Architecture of Cognition. Harvard University Press.

- Joan Bybee. (2006). “From usage to grammar: The mind’s response to repetition.” Language, 82(4), 711–733.

- Robert M. DeKeyser. (2017). “Knowledge and skill in SLA.” In S. Loewen & M. Sato (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Instructed Second Language Acquisition (pp. 15–32). Routledge.

- Nick C. Ellis. (2016). “Cognitive perspectives on SLA: The associative-cognitive CREED.” Second Language Research, 32(3), 341–359.

- Nick C. Ellis & Fernando Ferreira-Junior. (2009). “Construction learning as a function of frequency, frequency distribution, and function.” Modern Language Journal, 93(3), 370–385.

- Nick C. Ellis & Katrin Roehr-Brackin. (2018). “Implicit and explicit knowledge in second language learning, testing and teaching.” Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 40(2), 435–442.

- Aline Godfroid. (2020). “Implicit and explicit learning in SLA.” In B. VanPatten, G. D. Keating, & S. Wulff (Eds.), Theories in Second Language Acquisition: An Introduction (3rd ed., pp. 127–146). Routledge.

- Shaofeng Li. (2020). “Corrective feedback in L2 classrooms: A meta-analysis.” Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 42(4), 993–1020.

- Patsy M. Lightbown & Nina Spada. (2021). How Languages are Learned (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Roy Lyster & Yuko Saito. (2010). “Oral feedback in classroom SLA: A meta-analysis.” Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 32(2), 265–302.

- Ellen Bialystok McLaughlin. (1990). “Restructuring.” Applied Linguistics, 11(2), 113–128. (Note: McLaughlin’s 1990 “Restructuring” article is often cited simply under McLaughlin, 1990.)

- Kim McDonough. (2019). Cognition and Second Language Instruction. Cambridge University Press.

- Bill VanPatten. (1990). “Attending to content and form in the input: An experiment in consciousness.” Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 12(3), 287–301.

- Bill VanPatten. (2015). “Input processing in adult SLA.” In B. VanPatten & J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in Second Language Acquisition (2nd ed., pp. 113–134). Routledge.

- Manfred Pienemann. (1998). Language Processing and Second Language Development: Processability Theory. John Benjamins.

- Arthur S. Reber. (1993). Implicit Learning and Tacit Knowledge: An Essay on the Cognitive Unconscious. Oxford University Press.

- Yoichi Suzuki. (2021). “Relearning and the spacing effect in L2 grammar acquisition.” Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 43(5), 1092–1112.

- Robert M. DeKeyser & Nick C. Ellis. (Eds.). (2017). Implicit and Explicit Learning in Second Language Acquisition. John Benjamins.

- Stephen Krashen. (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Pergamon.

- Diane Larsen-Freeman. (1997). “Chaos/complexity science and second language acquisition.” Applied Linguistics, 18(2), 141–165.

- Peter Skehan. (1998). A Cognitive Approach to Language Learning. Oxford University Press.

- Nick C. Ellis. (2002). “Frequency effects in language processing.” Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 24, 143–188.

- John Truscott. (1996). “The case against grammar correction in L2 writing classes.” Language Learning, 46(2), 327–369.

- John Truscott. (1999). “The case for ‘The case against grammar correction in L2 writing classes’: A response to Ferris.” Journal of Second Language Writing, 8(2), 111–122.

- John Truscott. (2007). “The effect of error correction on learners’ ability to write accurately.” Journal of Second Language Writing, 16(4), 255–272.

- Nick C. Ellis & Lourdes Ortega. (Eds.). (2005). Handbook of Research in Second Language Teaching and Learning. Routledge.

- Lourdes Ortega. (2009). Understanding Second Language Acquisition. Routledge.

- John Williams. (2005). “Learning without awareness.” Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 27(2), 269–304.

You must be logged in to post a comment.