Every few months — sometimes more often than that — social media fills up with posts telling us that research proves a particular language-teaching method works best. You know the sort of thing. One week it is storytelling. The next week it is explicit grammar. The week after is EPI (Yes – guilty as charged!) Then it is “input only”, or “no output”, or whatever the label happens to be this time. The pattern never really changes.

And let me say this clearly before someone misreads what follows: the problem is rarely the research itself. The real problem is what happens after the research leaves the journal and enters the hands of people who are actively trying to justify selling their method, their training, their books, their conference slots, or their latest online course.

So, before we swallow yet another “research-backed” claim whole, it might be worth slowing down and asking a few boring but necessary questions… even if they spoil the excitement.

First of all: who were the learners in the study?

This sounds so obvious that it almost feels insulting to mention it, and yet it is ignored with remarkable consistency. Language learning looks very different depending on whether we are talking about preschool children, primary beginners, secondary pupils working towards exams, or university students who already have years of schooling behind them. Findings from one group do not automatically apply to another, no matter how confidently someone says they do. When studies involving very young learners, or learners with extremely limited language, are used to justify methods for GCSE or A-level classrooms, surely the correct response is not enthusiasm but caution… or at least a pause.

Second — and this is absolutely central — what level did the learners start from?

Baseline language ability is not a small technical detail tucked away in the methods section for researchers to worry about. In practice, it often explains more than anything else. When learners begin with almost no vocabulary, very little exposure to structured language, and limited experience of listening to or using language in organised ways, teaching does something very specific: it lays foundations. It does not suddenly accelerate learning in magical ways. So when an intervention produces gains in the exact words that were taught, but little beyond that, this is not surprising at all. It is exactly what we would expect. Using such findings to make claims about learners who already have years of exposure, larger vocabularies and basic narrative competence is not careful interpretation. It is misuse. Ignoring starting level is one of the easiest ways to turn sensible research into bad pedagogy.

Third: was the study actually about learning a second or foreign language?

This is where things often get very slippery. Research from first-language literacy or early childhood development is regularly brought into language-teaching debates as if the jump were obvious and unproblematic. Yes, storytelling helps children develop language in their first language. No, that does not automatically mean it drives grammatical development in a second language. The same mistake appears when research on first-language grammar is used to justify grammar-heavy second-language teaching. Different learning problems, different conditions, different outcomes… surely that matters?

Fourth: what did the researchers actually measure?

Did learners understand a story while it was being told? Did they recognise forms they had just seen? Did they do well on a test straight after instruction? Or did they show that they could use the language later, on their own, in new situations, without help? These are not minor distinctions. Much research reports short-term performance under controlled conditions, and that is fine. What is not fine is pretending that this is the same thing as long-term acquisition.

Fifth: was there a proper comparison group?

Without a meaningful comparison, improvement does not tell us very much. Learners usually improve over time anyway. Teachers get better. Familiarity with tasks increases. Comparing an intervention to “no instruction” might look impressive, but it tells us almost nothing about whether the approach is better than other plausible alternatives.

Sixth: did the gains last?

Were learners tested again weeks or months later, or was everything measured immediately, while the material was still fresh? Without delayed testing, claims about learning should be treated with extreme caution. Short-term gains are easy to produce. Long-term retention is much harder. We have known this for well over a century, and yet it is routinely ignored… why?

Seventh: was grammar actually tested in free use?

Doing well in gap-fills, multiple-choice tasks, or highly scaffolded activities is not the same as using language accurately when speaking or writing under pressure. Too often, grammar learning is assumed rather than demonstrated. We should be asking whether learners can actually use what they supposedly “acquired”, not whether they can recognise it when prompted.

Eighth: is one element being sold as the whole solution?

Input matters. So does practice. So does feedback. So does retrieval. So does time. When one of these is isolated and presented as the answer, something has gone wrong. No serious account of learning supports the idea that a single ingredient, however valuable, can replace everything else.

Ninth: what do the authors themselves say about limits?

Most researchers are careful. They talk about context. They talk about constraints. They warn against overgeneralisation. When these warnings quietly disappear in conference talks or social-media posts, that should worry us. If the caveats are gone, the research has already been bent out of shape.

Finally: who stands to gain from this interpretation?

This is uncomfortable, but unavoidable. When claims are tied to training packages, branded methods, books, or speaking circuits, there is an incentive to oversell. That does not automatically make the research wrong. But it should make us sceptical… very sceptical.

An example: recent social-media claims about TPRS

A example: recent claims made online by a TPRS advocate, suggesting that a randomised controlled study carried out with African preschool children somehow supports storytelling as an effective general language-teaching method.

It does not.

The study looked at a structured story-based intervention delivered to very young children from low-income backgrounds who started with extremely weak language. The children improved on the vocabulary that was explicitly taught to them. That is a sensible and useful finding. What it does not show is that storytelling leads to broad second-language acquisition, that it replaces explicit instruction, or that it applies to older learners in secondary schools. The learners were preschoolers. Their starting level was extremely low. The effects were narrow and closely tied to what was taught. The context was highly specific. And the authors themselves warned against overgeneralisation.

Turning that into an argument for TPRS as a general solution is not research-informed practice. It is spin. After all, TPRS has been around for ages, yet it is a very niche approach in secondary education. Even if we ignore the research misuse, there are practical reasons why TPRS has never really taken hold in mainstream state secondary education. It depends heavily on unusually skilled and confident teachers. It makes syllabus coverage difficult to guarantee. It works far better with beginners than with learners who need increasing accuracy. It does not align well with exam demands. And it takes time — time that most state schools simply do not have.

None of this means storytelling is useless. It means it is limited. And whilst it is one of many instructional strategies that can be used once or twice a term to add variety and spice up the curriculum, it cannot be the one and only method to use with students who will be sitting a high-stake national exam which does not involve storytelling. This is not because I don’t espouse or like this method; but, rather, because, as cognitive psychology teaches us, what one learns through storytelling doesn’t transfer to the tasks used to assess students in national examinations around the world!

Another example: The Finnish miracle… and the context everyone forgets

The same pattern shows up well beyond language teaching, and the way Finland has been held up for years – based on credible research studies – as proof that there is a single “better” way to teach is probably the clearest example of this problem. Finnish education has been praised, copied, packaged and exported as if it were a set of techniques rather than the product of a very particular country, culture and history. Although the research backing the effectiveness of Finnish education is absolutely credible, what tends to be ignored is that Finland is small, socially cohesive, linguistically homogeneous, and built on unusually high levels of trust in teachers, low child poverty, strong welfare support, and minimal inequality between schools. Teachers are highly selected, highly trained, and enjoy professional autonomy that would be politically impossible in many systems. Classrooms operate in a context where behaviour, attendance, parental support and social safety nets are not constant battles. To point at Finnish outcomes and say “do this and you will get the same results” is to ignore all of that… and yet this is exactly what happens. The method is praised, the context quietly disappears, and what was once careful comparative research turns into a convenient story that sounds great in conferences, policy documents and consultancy brochures, but tells us very little about what will actually work in crowded, exam-driven, high-stakes state school systems elsewhere.

Conclusions

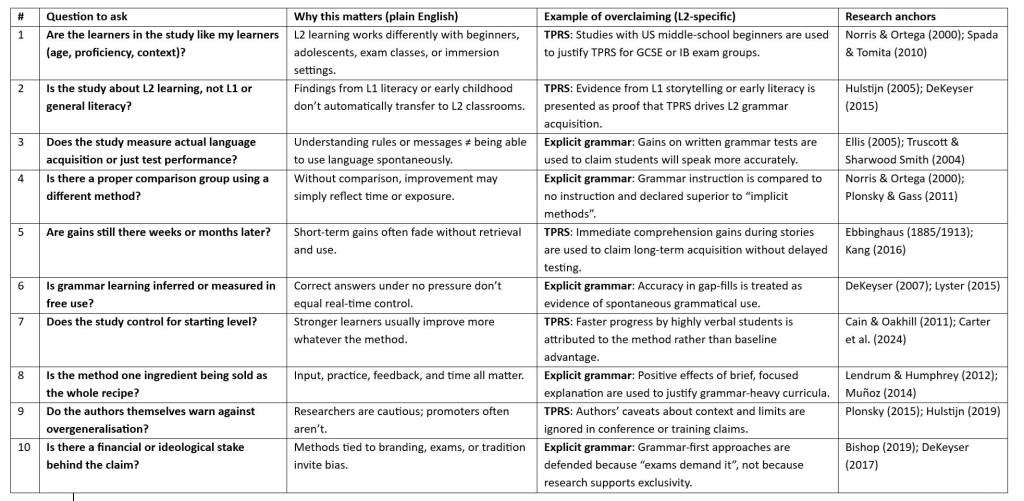

Storytelling has value. Explicit grammar has value. Input has value. Practice has value. EPI has value. But when any of these is turned into the answer, backed by selective readings of research and pushed hard by snake-oil salesmen who have something to sell, teachers should stop, breathe, and ask the very dull questions in the table below.

Research does not give us silver bullets. It gives us boundaries. When those boundaries disappear, what we are left with is not innovation or evidence-based teaching, but marketing dressed up as science. And frankly, we should be tired of that by now…

You must be logged in to post a comment.