Introduction

When we teachers pick a listening text, it is easy to go with our gut feeling: “This one sounds a bit harder,” or “It is slower so the pupils will understand it.” But in truth, the reasons why a listening text is difficult are many and often not very obvious.

In this post I want to share—very simply—what the research tells us. My hope is that it helps you, as it helped me over the years, to see clearly what makes a text tricky so you can choose or create materials that truly suit your learners. I will first describe the main factors, then give my own thoughts on what this means for how we teach listening.

Eight Buckets of Listening Difficulty

1. The Sound of the Message: Acoustic and Signal Factors

The first challenge is, of course, the sound itself – the sound barrier that Steve and I allude it in the title of our book (Conti and Smith, 2019). If the speaker talks quickly or suddenly speeds up, pupils have very little time to process what they hear (Griffiths, 1992; Field, 2008). And even when the speed is not high, connected speech—liaison, elision, assimilation—can make the words melt together (Brown & Kondo-Brown, 2006).

Weak vowel sounds, unexpected stress patterns and unfamiliar accents add, of course, more work for the ear (Rost, 2016). Poor recording quality or background noise can be as damaging as a strong accent. Small hesitations, laughter or sudden changes of emotion in the speaker also catch pupils off guard.

2. Following the Conversation: Interactional Factors

Texts with several speakers are naturally harder for obvious reasons: the listener must keep track of who is talking, manage overlapping voices and cope with quick turn-taking (Buck, 2001; Wagner, 2010). I often notice even strong pupils lose the thread when two people talk over each other.

3. Words and Meaning: Lexical–Semantic Factors

The vocabulary load of a text is, of course, one of the strongest predictors of how well pupils will understand it, since, as I often reiterate in my blog, 70 to 90 % of success at listening tasks hinges on word recognition. When a passage is packed with content words (nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs) —what researchers call high lexical density — working memory is quickly stretched (Vandergrift & Goh, 2012).

Equally important is lexical coverage, the percentage of words the listener already knows. Studies show that learners generally need to know around 95 % of the running words for basic comprehension and close to 98 % for comfortable, detailed understanding (Laufer, 1989; Nation, 2006, 2013). If coverage drops below that threshold, even confident pupils spend so much effort guessing unknown words that the overall message slips away.

Topic familiarity is another key factor: when the theme is new, pupils cannot draw on background knowledge to predict meaning (Chiang & Dunkel, 1992). And of course the usual culprits remain: low-frequency words, idioms, false friends, numbers, dates and proper nouns are classic stumbling blocks (Field, 2008; Nation, 2013).

Finally, some languages add an extra twist—rich morphology can blur word boundaries, which in my opinion is one of the hardest elements to teach explicitly (Rost, 2016).

4. Grammatical Complexity: Syntactic Factors

Texts containing subordinate clauses, embedded structures, long noun phrases, multiple negatives or unusual word orders are more challenging as these features all increase the mental effort needed to hold information while the sentence continues (Buck, 2001; Field, 2008).

5. How the Text Is Organised: Discourse and Genre

Different genres—narrative, interview, public announcement—signal meaning in different ways. When discourse markers are weak or missing, pupils can easily miss topic changes or elliptical references (Flowerdew & Miller, 2005). I often see this when students listen to authentic interviews where speakers jump from one idea to another.

6. Culture and Pragmatics

Irony, humour, politeness formulas and culture-specific references call for more than vocabulary; they rely on shared cultural knowledge and pragmatic inference, which, in my experience are rarely explicitly taught (Rost, 2016; Vandergrift & Goh, 2012). Even a simple sentence can mislead when this knowledge is absent.

7. The Listener’s Own Resources

Not all the difficulty is in the text. Working-memory limits, tiredness or anxiety often explain a poor result more than the audio itself (Macaro, Graham & Vanderplank, 2007).

Learners who have not developed metacognitive habits—planning, monitoring, evaluating—will struggle even with familiar topics (Graham & Macaro, 2008; Vandergrift & Goh, 2012). From my own classroom I can say that a calm, confident pupil usually hears more than a nervous one.

8. The Task and the Assessment Frame

Finally, the way we test or exploit the text matters. If the question order does not follow the text, if there is no visual support, or if distractors and negative wording are used, the task itself raises the level of challenge (Buck, 2001; Field, 2019). The new GCSE listening papers often include exactly these features.

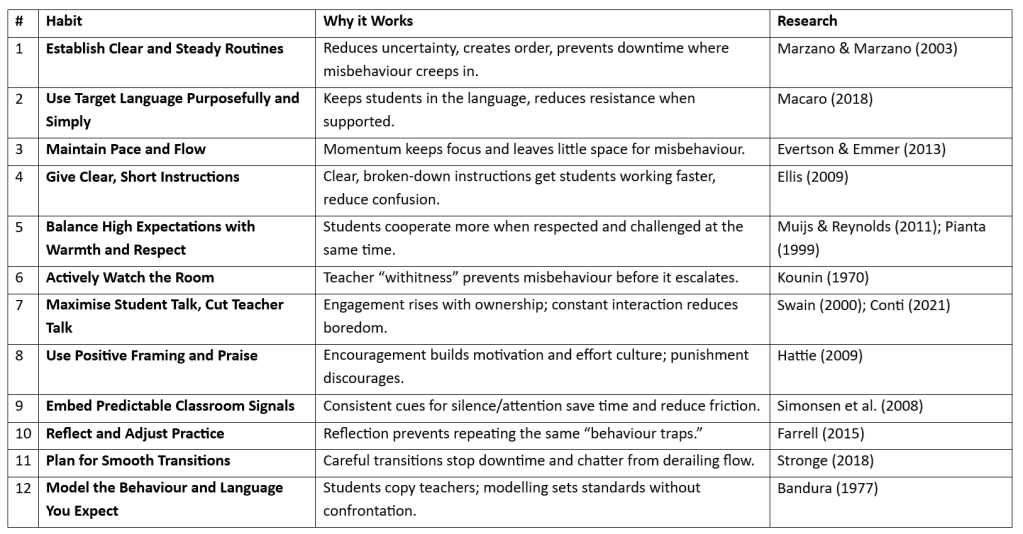

Table 1 – Summary

From KS3 to KS4: Why This Matters

The step from lower secondary (KS3) to the new GCSE is not only about “more difficult vocabulary”. Exam papers deliberately increase multi-speaker interactions, speed up delivery, broaden topics and remove many visual cues (Ofqual, 2021). Pupils who have grown used to carefully graded KS3 recordings can suddenly face a much heavier cognitive load.

Implications for Listening Instruction

1. Audit and Anticipate

Use the eight buckets as a difficulty checklist whenever you select or write a text. Decide which factors will probably trip up your learners and plan support in advance—perhaps pre-teach key chunks (Webb & Nation, 2017), run a short phonology warm-up, or model turn-taking signals.

2. Teach Listening for Learning, Not Only for Testing

Field (2008, 2019) argues that listening lessons should build skill, not simply rehearse exams. Give pupils several purposeful listens—prediction, gist, detail—then use diagnostic listening: show the transcript, ask them to mark what they misheard and discuss why. After that, I like to run quick “Fix & Re-train” tasks such as minimal-pair drills or shadow-reading of the lines they found hardest.

5. Check or estimate lexical coverage

When selecting or writing a listening text, it is key to check or estimate lexical coverage. Sadly, this is not commonly done If your learners know far less than 95 % of the words:

- Pre-teach the most useful new chunks before the first listen (Webb & Nation, 2017).

- Or simplify the text so that unknown items fall within that 2–5 % “tolerable” window.

This small step often makes the difference between a frustrating and a genuinely instructive listening lesson.

Don’t rely on the fact that some of the unknown vocabulary consists of cognates, as research consistently finds that roughly a third of obvious cognates go unrecognised in L2 listening – see Weber & Cutler (2004) and Broersma & Cutler (2011) – a gap teachers should address when preparing pupils for real-world or GCSE-style listening tasks

4. Place Listening Inside an Input→Output Sequence

Comprehension rises when key vocabulary is taught before the first listen (Webb & Nation, 2017). This is the Input-Plus condition described by Krashen (1985): input just above the learner’s level, paired with meaningful focus.

My PIRCO cycle puts this into practice:

- P – Priming: model key lexis and sounds, use a short reading text,

- I – Input: three purposeful listens,

- R – Review: quick reflection on strategies,

- C – Consolidation: diagnostic listen and Fix & Re-train,

- O – Output: structured speaking or writing tasks.

5. Let PIRCO Grow with the Learners

- KS3: keep PIRCO strong—plenty of priming and a full diagnostic stage.

- Year 10 and early Year 11: move to a medium version—priming in one lesson, a shorter diagnostic phase, grammar and structured output follow quickly.

- Exam run-up (Year 11 Term 2): switch to PIR—quick priming and exam-style listening; most consolidation and output happen elsewhere.

6. Build Metacognitive Habits

Encourage pupils to plan, monitor and evaluate (PME) their listening (Vandergrift & Goh, 2012). Even a short checklist—“Before I listen I will… During I will… After I will…”—can help them become more independent. In my opinion, this small routine pays off far more than an extra comprehension exercise. PME, too is routinely and seamlessly built in the PIRCO cycle.

Conclusions

Fast speech is only the tip of the iceberg. The real challenge of aural texts lies in a network of factors: the sound signal, the way speakers interact, the words and grammar they choose, and even the test format itself.

By recognising these eight areas and by scaffolding listening through a PIRCO-based input–to–output sequence, we can select or create texts that fit our classes much more precisely. In my own experience, this careful matching—together with clear metacognitive routines—helps students cross the KS3→KS4 bridge with far greater confidence and prepares them not only for the new GCSE but for real communication beyond the exam hall.

Key References

Buck, G. (2001). Assessing Listening. Cambridge University Press.

Chiang, C. & Dunkel, P. (1992). TESOL Quarterly, 26(2).

Field, J. (2008). Listening in the Language Classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Field, J. (2019). In The Cambridge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition.

Flowerdew, J. & Miller, L. (2005). Second Language Listening: Theory and Practice.

Graham, S. & Macaro, E. (2008). Language Learning, 58(4).

Griffiths, R. (1992). Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 14(3).

Krashen, S. (1985). The Input Hypothesis.

Macaro, E., Graham, S. & Vanderplank, R. (2007). Language Teaching, 40(2).

Nation, I. S. P. (2013). Learning Vocabulary in Another Language (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Rost, M. (2016). Teaching and Researching Listening (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Vandergrift, L. & Goh, C. (2012). Teaching and Learning Second Language Listening. Routledge.

Webb, S. & Nation, P. (2017). International Review of Applied Linguistics, 55(1).

Wagner, E. (2010). TESOL Quarterly, 44(4).

You must be logged in to post a comment.