Introduction

Teaching language by topics in Instructed Second Language Acquisition (ISLA) is a common approach, but research shows both advantages and disadvantages. Here’s a breakdown of the pros and cons based on current findings in ISLA literature:

Pros of Teaching Language by Topics

- Enhanced Motivation and Engagement

- Research suggests that topic-based instruction increases learners’ interest, as it connects language learning to real-life contexts (Dörnyei, 2009).

- Topics can be tailored to learners’ interests, making learning more meaningful (this is key!).

- Improved Vocabulary Retention

- Thematic instruction helps learners acquire and retain vocabulary more effectively because words are introduced in meaningful contexts (Nation, 2001).

- Semantic clustering within a topic can aid memory recall (Schmitt, 2008).

- Supports Communicative Language Teaching (CLT)

- Topics provide a natural framework for discussion, making it easier to integrate speaking and listening activities.

- Encourages real-world language use and pragmatic competence (Ellis, 2005).

- Promotes Deeper Processing

- Learners are more likely to process language at a deeper cognitive level when it is linked to a coherent theme (Swain, 2005).

- Supports meaningful interaction and content-based learning.

- Facilitates Cross-Curricular Learning

- Topic-based learning allows integration with other subjects (e.g., history, science), which can lead to content and language-integrated learning (CLIL) benefits (Dalton-Puffer, 2011).

Cons of Teaching Language by Topics

- Limited Grammar Focus

- Topic-based teaching often prioritizes vocabulary and communicative skills over explicit grammar instruction, which may hinder grammatical accuracy (DeKeyser, 2007), an issue that can be easily tackled through careful planning.

- Some structures may not naturally arise in certain topics, leading to gaps in grammar coverage. Another issue that can be overcome through careful planning.

- Potential Overload of Semantic Clustering

- Research suggests that presenting too many related words at once (e.g., all fruit names) may hinder learning due to interference effects (Waring, 1997). This issue can be mitigated by selecting the target words in such a way that words which are too similar in meaning (e.g. ‘truck’ and ‘van’ are not taught in the same set).

- Mixed or spaced exposure might be more effective than strict topic-based learning (Webb, 2007). Nothing stops a teacher from revisiting and reviewing material learnt during Unit 1 on topic A when teaching Unit 2 on topic B, especially if you sequence topics which are semantically related (e.g. Unit 1 = Leisure, Unit 2 = Healthy living, Unit 3 = My daily routine).

- Lack of Systematic Progression

- If not carefully planned, topic-based instruction may lead to gaps in linguistic knowledge because it doesn’t always follow a structured progression of difficulty (Pienemann, 1998).

- Learners may struggle with cumulative language development if topics do not build on each other in a logical sequence. This issue and the previous one can, yet again, be solved through careful planning.

- Difficulty in Addressing Individual Needs

- Some learners may need specific grammatical structures or language functions that do not fit into the selected topics.

- Individualized learning paths might be harder to implement within a fixed topic framework.

- May Not Align with Standardized Testing Goals

- Topic-based approaches might not cover all the grammar and vocabulary required in standardized assessments (Alderson, 2005). This requires some creativity on the part of the curriculum designer, but can be solved by embedding such items in texts and tasks.

- Test-oriented learners may feel unprepared if explicit instruction is lacking and the topics are not aligned with the tests.

Conclusion

Teaching by topics can be highly effective for engagement, vocabulary acquisition, and communicative competence. However, for a balanced ISLA approach, it should be supplemented with explicit grammar instruction, varied input, and opportunities for structured language practice.

A hybrid approach that combines topic-based instruction with form-focused activities (e.g., EPI, task-based language teaching or focus on form) may offer the best outcomes (Ellis, 2016). The devil is always in the detail; if you are working towards a specific exam, you can always embed in whatever topic you have chosen to teach texts and activities containing language items extraneous to that topic. All you need is a bit of creativity, but it can be done. By breaking down a topic in sub-topics centred around communicative function, it is fairly easy to cover specific grammar structures.

As far as motivation is concerned, it is key to select topics and sub-topics which are relevant to the target children, as relevance is key. When the topics are mandated by the examination boards, then it is crucial to at least teach words the students are likely to be interested in learning. And when these words fall outside the lists mandated by the examination board, as may happen with the new MFL GCSE in England, one has to heed the children’s wants and strike a balance by adding some vocabulary items in the mix for relevance and motivation’s sake.

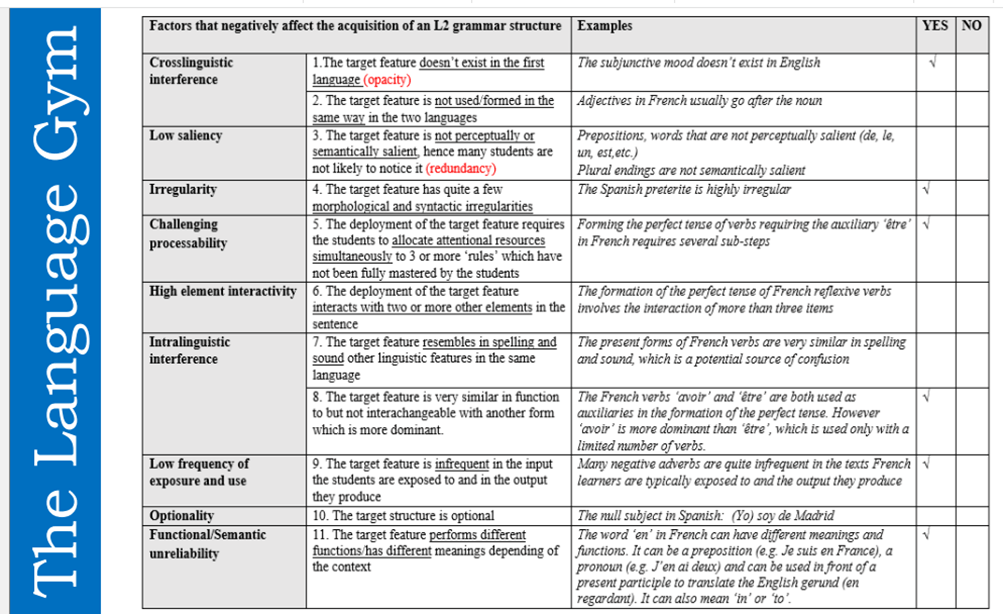

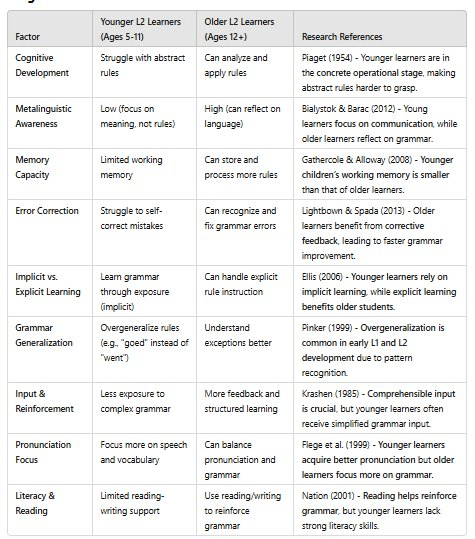

When it comes to the important issue of grammar progression, the curriculum deisgner needs to heed learnability theory (see this post of mine) and sequence the topics in such a way that the challenge stays always within the zone of optimal development. This doesn’t always happen with UK-published textbooks, where the selection of the grammar is quite random.

With regard to the interference issue, i.e. words from lexical sets centred on a given topic interfering with one another, research shows that it is mostly at play when words sound similar (‘jaune’ and ‘jeune’ in French) or when they have similar meanings (e.g. ‘mignon’ and ‘joli’ in French). Also, the evidence that such interference occurs comes mainly from lab experiments where the target words are mostly taught out of context, and in lists. In my experience, if words are taught multimodally, including using unambiguous visual aids, in learnable amounts, in context and through the multiple encounters with the words suggested by research (e.g. 15 minimum through the receptive skills) the issue is easily overcome.

Finally, as long as interleaving of key structures and vocabulary is concerned, it can be done even when teaching thematically. It is just a matter of selecting and sequencing the topics carefully; using my cumulative texts and tasks strategy; having an intelligent retrieval practice schedule in which language items from the various units are interleaved at space intervals, etc.

References

- Alderson, J. C. (2005). Diagnosing foreign language proficiency: The interface between learning and assessment. Continuum.

- Dalton-Puffer, C. (2011). Content-and-language integrated learning: From practice to principles? Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 31, 182–204.

- DeKeyser, R. (2007). Practice in a second language: Perspectives from applied linguistics and cognitive psychology. Cambridge University Press.

- Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self system. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 9-42). Multilingual Matters.

- Ellis, R. (2005). Principles of instructed language learning. System, 33(2), 209-224.

- Ellis, R. (2016). Focus on form: A critical review. Language Teaching Research, 20(3), 405-428.

- Nation, I. S. P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge University Press.

- Pienemann, M. (1998). Language processing and second language development: Processability theory. John Benjamins.

- Schmitt, N. (2008). Review article: Instructed second language vocabulary learning. Language Teaching Research, 12(3), 329-363.

- Swain, M. (2005). The output hypothesis: Theory and research. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (Vol. 1, pp. 471-483). Routledge.

- Waring, R. (1997). A study of receptive and productive learning from word cards. Studies in Foreign Language Education, 12, 94–114.

- Webb, S. (2007). The effects of synonymy on second-language vocabulary learning. Applied Linguistics, 28(1), 1-22.

You must be logged in to post a comment.