Introduction

Second language acquisition (SLA) research strongly indicates that learners need to understand the vast majority (around 90–98%) of the language input they receive for optimal learning. This high level of comprehensible input ensures that learners can focus on gradually absorbing new elements (the i+1 content) without being overwhelmed. Below, we explore key research-backed reasons why 90–98% comprehensible input is considered ideal, with supporting studies from prominent SLA scholars like Stephen Krashen, Paul Nation, Norbert Schmitt, Batia Laufer, and others.

The Research evidence

There is plenty of research evidence to support the notion that students need 95 to 98% comprehensible input in order to grow linguistically. Table 1 below summarizes ten key studies which put this assumption to the test.

Cognitive Load and Processing Capacity

Cognitive load theory (Sweller, 1988) suggests that the brain has a limited capacity for processing new information at any given time. When learners are exposed to language that is too difficult (e.g., less than 90% comprehensible), the cognitive load becomes too high. This makes it difficult for learners to process and internalize new language structures and vocabulary because too much effort is spent trying to understand the meaning. On the other hand, when 90% to 98% of the input is comprehensible, learners can process new vocabulary and structures while still understanding the overall meaning, which facilitates automaticity—the ability to process language quickly and accurately.

Bill VanPatten (1990) demonstrated that second-language learners are limited-capacity processors who naturally pay attention to meaning before form; if they must struggle to decode too many unknown words or complex structures, their brains have little bandwidth left for learning new language features. In other words, when input is 90–98% familiar, learners can devote cognitive resources to noticing and acquiring the small amount of new language (the remaining 2–10%) without being overwhelmed. VanPatten’s findings (Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 1990) showed that splitting attention between understanding meaning and analyzing form led to lower comprehension when input was too difficult, underscoring the need for mostly comprehensible input to keep cognitive load manageable.

This aligns with Cognitive Load Theory (Sweller, 1988) in that excessive unfamiliar material in input imposes extraneous load, impeding efficient learning. Thus, a high percentage of known input ensures learners can process language meaningfully and transfer new items from working memory to long-term memory.

The Optimal Zone of Challenge (i+1)

Stephen Krashen’s Input Hypothesis (Krashen, 1985) famously asserts that we acquire language by understanding input that contains a bit beyond our current level – he labeled this ideal input as “i+1”, meaning our current interlanguage state plus one level. Crucially, Krashen emphasizes that input must be comprehensible for that one step beyond to be absorbed: “We acquire by understanding language that contains structure a bit beyond our current level of competence (i+1). This is done with the help of context or extra-linguistic information.” (Krashen, 1985, The Input Hypothesis).

In practice, this means learners should already know 90%+ of the words and structures in a message so that the few new items (the +1) are supported by context and understood in meaning. If the input is too far beyond (i+2, i+3, etc.), it ceases to be comprehensible and acquisition stalls. Effective input, according to Krashen, “need not contain only i+1” as long as it is largely understood; when communication is successful, the necessary i+1 is provided automatically by context and negotiation of meaning.

This concept mirrors Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development in that the ideal challenge level is just above the current ability. Paul Nation (2013) likewise notes that “quality input” for learning should be at a level where only a small percentage of vocabulary is unknown, ensuring the text or speech is in an optimal zone of difficulty that promotes growth without causing frustration. In sum, research supports that 90–98% known input hits the sweet spot: it contains enough familiar language to be understood and just enough new language to push development. This i+1 zone maximizes acquisition by providing a manageable challenge.

Vocabulary Acquisition

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for needing ~95–98% comprehensible input comes from vocabulary studies. In order for learners to acquire new words incidentally (through reading or listening) and understand the overall content, they must know the large majority of the words in the input.

Batia Laufer (1989) found that learners generally need to understand at least 95% of the words in a text to adequately grasp its meaning. At about 95% lexical coverage (i.e. only 1 unknown word in 20), readers could get “adequate” comprehension, whereas below that threshold comprehension dropped dramatically. More recent research has pushed the target higher: Hu and Nation (2000) concluded that around 98% vocabulary coverage may be necessary for full, unassisted comprehension. In a controlled study, Hu & Nation presented learners texts with varying percentages of known words; the learners generally needed to know 98–99% of the words to answer comprehension questions satisfactorily, whereas at 95% many struggled. Norbert Schmitt et al. (2011) reinforced these findings in a large-scale experiment with 661 learners, noting a nearly linear relationship between vocabulary coverage and reading comprehension – as the percentage of known words rose, comprehension scores rose in tandem. They found no sudden “cliff” but did argue that 98% coverage is a more reasonable target for comfortable reading of academic texts.

In practical terms, Paul Nation (2006) calculated that achieving 98% coverage in typical written texts requires a vocabulary size on the order of 8,000–9,000 word families (for reference, 95% coverage might require ~3,000 word families).Nation’s analysis (“How Large a Vocabulary Is Needed for Reading and Listening?”, CMLR, 2006) underscores that the last few percent of coverage (from 95% up to 98%) have a big impact on comprehension. If only 80–90% of words are known (so 10–20% unknown), comprehension plummets and guessing meaning becomes unreliable.

Thus, vocabulary research supports providing learners with input (such as graded readers or leveled listening) where they know almost all the words, so that they can pick up the remaining few new words through context with relative ease. High coverage input not only aids immediate understanding but is also far more effective for incidental vocabulary acquisition. For example, Nagy, Herman, and Anderson (1985) found that each encounter with an unfamiliar word in a meaningful, comprehensible context can yield a small gain (5–10% of the word’s meaning on average). While 5–10% may seem minor, they noted that with enough comprehensible input, such incremental gains account for a large portion of vocabulary growth

In sum, numerous studies (Laufer, 1989; Nation, 2006; Schmitt et al., 2011, among others) point to 95% as a minimal lexical coverage for basic comprehension and 98% as optimal for substantial comprehension and vocabulary learning. This is why extensive reading and listening programs emphasize that texts should be 95–98% understandable to facilitate word learning.

Grammatical Structures and Syntax

Comprehensible input helps learners not only acquire vocabulary but also internalize grammatical structures. If too many grammatical structures are beyond their current understanding (less than 90% comprehensible), learners are likely to focus on trying to understand the meaning at the expense of learning the syntax (sentence structure) and morphology (word forms) of the language.

Input at the 90% to 98% level allows learners to make hypotheses about grammatical rules by encountering sentences that are just challenging enough for them to test their understanding. This kind of input supports both implicit learning (learning without conscious effort) and explicit learning (conscious awareness of language rules).

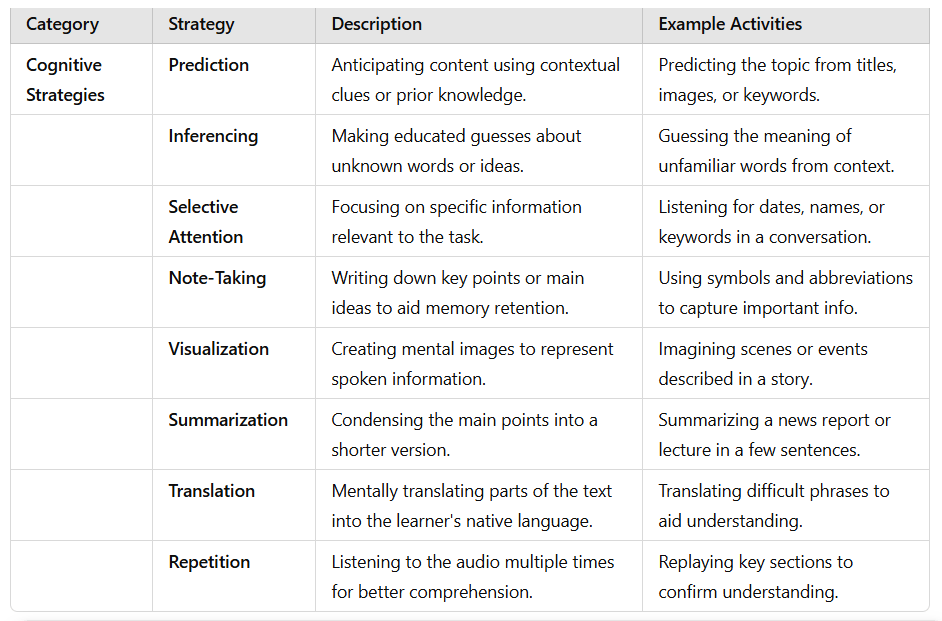

Contextual Clues and Inferencing

Comprehensible input provides the necessary backdrop for learners to make use of contextual clues and inference strategies to learn new language elements. If most of a sentence or discourse is understood, a learner can often guess the meaning of an unfamiliar word or deduce a grammatical function from context. However, this process only works when the proportion of unknown elements is low. Liu & Nation (1985) found that guessing unknown word meanings from context is rarely successful unless about 95% of the surrounding words are already familiar.

.At lower levels of comprehension, learners’ inferencing often fails or leads to misunderstanding. For example, if a learner knows only 80% of the words in a text, the unknown 20% provide very little reliable clue to each other, akin to solving a puzzle with too many missing pieces. By contrast, at 95–98% known-word coverage, the context is rich enough to support educated guessing: the known parts of the sentence constrain the possible meanings of the unknown item. Nation (2001) notes that with high coverage, learners can use cues like redundancy, prior knowledge, and linguistic context to fill in gaps, gradually building their vocabulary through inference. Indeed, Nagy et al. (1985) estimated that when context is fully understood, learners gain a partial understanding of new words (a small percentage of meaning) with each encounters.

Multiple encounters in varied contexts then refine and solidify the word’s meaning. This means that incremental vocabulary learning through context is feasible only when input is comprehensible enough to make those first guesses. Paul Nation (2013) has pointed out that to infer word meaning from context, learners not only need a high percentage of known words, but also familiarity with the subject matter and discourse pattern. For example, a student reading a simplified story (with 98% known words) can often infer the remaining 2% (say, a new adjective or an unknown idiom) because the storyline and surrounding text make the meaning clear. If that same student tried a text with only 80% known words, they would likely resort to dictionary look-ups or simply not understand enough to infer anything useful. Research has also shown that incorrect inferences are common when coverage is low, which can mislead learners. Thus, maintaining 90–98% comprehensibility is key to leveraging context: it allows learners to use the known language to learn the unknown. Over time, this process contributes significantly to vocabulary expansion and comprehension skills. In short, comprehensible input provides a supportive context that permits effective inference and hypothesis-testing by the learner, whereas input with too many unknowns offers a poor context that can lead to frustration or false guesses. This is one reason extensive reading proponents like Nation and Norbert Schmitt advocate using reading materials at an appropriate level of difficulty (often defined by that 95–98% coverage ratio). With adequately comprehensible input, learners become adept at “learning to learn” from context, an essential skill for autonomous language growth.

Affective Considerations

Learners’ emotional and psychological states can influence how much they benefit from input. When input is too difficult (e.g., below the 90% comprehension threshold), learners may experience frustration, anxiety, and reduced motivation, leading to a high affective filter that blocks language acquisition. Evelyn Hurwitz and Dolly Young’s studies on foreign language anxiety (Horwitz et al., 1986) showed that anxious students comprehend and retain less of the L2 input in classroom settings. They essentially have a “mental block” – Krashen’s metaphorical affective filter – that makes input go “in one ear and out the other.

Conversely, when input is mostly understandable (90-98%), learners are more likely to experience engagement and positive emotional responses, which lowers the affective filter and enhances learning.

Incremental Learning and Transfer (Transfer Appropriate Processing)

Language acquisition is a gradual, cumulative process, and the principle of incremental learning holds that learners build proficiency step by step through repeated exposure and practice. Comprehensible input at the right level facilitates this incremental learning by ensuring each new encounter reinforces existing knowledge and adds a small layer of new information. For example, a learner might first understand a sentence globally, then notice a new word in it, then later encounter that word in another sentence and refine their understanding, and so on. If input is too difficult, this incremental build-up cannot happen because the learner isn’t even sure what is being communicated.

The incremental nature of learning is supported by comprehensible input because it allows repeated exposures. A word or structure that is initially new (the +1) in one input will appear again in subsequent inputs, each time with the learner understanding more of it – this spaced, contextual repetition solidifies learning and aligns with principles of memory (e.g. spaced repetition, contextual encoding).

In sum, comprehensible input enables a cycle of incremental learning: each understandable encounter adds a bit to the learner’s competence, and because these encounters are in meaningful contexts, the learning is “tuned” to real communication (transfer-appropriate). As Lightbown (2008) notes, when instruction and practice mirror the desired use (e.g. understanding stories to improve listening comprehension skill), learners show better retention and ability to apply their knowledge beyond the classroom.

This justifies methodologies like extensive reading, task-based learning, and story listening, which provide iterative, contextualized input at the right level. They ensure that knowledge is acquired in the same way it is needed for later use, making the transfer from learning to real-world communication as seamless as possible.

Conclusion

The research consistently underscores the critical importance of providing second language learners with comprehensible input that is 90–98% familiar in order to maximize their acquisition of both vocabulary and grammar. This input, which is just beyond their current level (i+1), allows learners to engage in meaningful, context-rich language use while still being challenged by a manageable amount of new material. Whether it’s through managing cognitive load, fostering incidental vocabulary acquisition, or supporting implicit grammar learning, comprehensible input lays the foundation for effective language development.

Moreover, the role of context and affective factors further emphasizes that language learning is not just a cognitive exercise but a holistic experience. The Affective Filter Hypothesis reminds us that learners must be in a supportive, low-anxiety environment for input to be absorbed efficiently. High levels of comprehension and emotional comfort together create the optimal conditions for second language acquisition.

In practice, this means that language instructors should focus on providing students with abundant, comprehensible input, through activities such as extensive reading, conversation, and content-based learning. By ensuring that the majority of the input is understood while still introducing small challenges, teachers can help learners gradually expand their language abilities. As research suggests, comprehensible input not only promotes effective learning but also ensures that students are equipped to transfer their newly acquired knowledge to real-world language use.

References:

- Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Pergamon Press. (See especially the Input Hypothesis and Affective Filter Hypothesis for the role of comprehensible input and emotional factors in SLA.)

- Krashen, S. (1985). The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications. Longman. (Introduces the i+1 concept, arguing that acquisition occurs with input just beyond the current level, in low-anxiety environments.)

- Laufer, B. (1989). “What percentage of text-lexis is essential for comprehension?” Ceben (In: Special Language: From Humans to Thinking Machines, ed. by C. Lauren & M. Nordman). (Pioneer study suggesting ~95% of words need to be known for adequate text comprehension.)

- Hu, M. & Nation, P. (2000). “Unknown Word Density and Reading Comprehension.” Reading in a Foreign Language, 13(1), 403–430. (Found learners needed 98% lexical coverage for satisfactory reading comprehension

- Nation, I.S.P. (2006). “How Large a Vocabulary Is Needed For Reading and Listening?” Canadian Modern Language Review, 63(1), 59–82. (Vocabulary size estimates for 95% vs. 98% coverage; ~8,000–9,000 word families for 98% coverage

- Schmitt, N., Jiang, X., & Grabe, W. (2011). “The Percentage of Words Known in a Text and Reading Comprehension.” Modern Language Journal, 95(1), 26–43. (Empirical study showing a near-linear increase of comprehension with higher known-word percentages; supports 98% coverage target.)

- Liu, N. & Nation, P. (1985). “Factors Affecting Guessing Vocabulary in Context.” RELC Journal, 16(1), 33–42. (Concluded learners need around 95% familiar words in a text to guess unknown words with reasonable success.)

- VanPatten, B. (1990). “Attending to Form and Content in the Input: An Experiment in Consciousness.” Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 12(3), 287–301. (Demonstrated that learners process input for meaning before form; too much new information can hinder form acquisition.)

- VanPatten, B., Keating, G., & Leeser, M. (2012). “The Eye-Tracking Study of Attention to Form in Spanish L2 Learners.” (As referenced in VanPatten’s work – showed that morphological details are acquired via input, not by isolated practice.)

- Bardovi-Harlig, K. (2000). Tense and Aspect in Second Language Acquisition: Form, Meaning, and Use. Blackwell. (Provided evidence that learners acquire complex grammatical systems like tense/aspect gradually and in piecemeal fashion, often independent of explicit instruction.)

- Lightbown, P. M. (2008). “Transfer Appropriate Processing as a Model for Classroom Second Language Acquisition.” In Z. Han (Ed.), Understanding Second Language Process (pp. 27–44). Multilingual Matters. (Argues that practice/learning conditions should match target use conditions for best retention and transfer – supporting use of meaningful, contextualized input in class.)

- Nagy, W., Herman, P., & Anderson, R. (1985). “Learning Words from Context.” Reading Research Quarterly, 20(2), 233–253. (Found that incidental exposure in context leads to small incremental gains in word knowledge, which accumulate given sufficient reading.)

- Dulay, H. & Burt, M. (1977). “Remarks on Creativity in Language Acquisition.” In M. Burt, H. Dulay, & M. Finocchiaro (Eds.), Viewpoints on English as a Second Language (pp. 95–126). Regents. (Originated the concept of the affective filter, later incorporated by Krashen, noting how negative emotion can impede language uptake.)

- Horwitz, E., Horwitz, M., & Cope, J. (1986). “Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety.” Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125–132. (Detailed how anxiety can negatively affect learners’ classroom performance and presumably their processing of input.)

- Morris, C., Bransford, J., & Franks, J. (1977). “Levels of Processing versus Transfer Appropriate Processing.” Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 16(5), 519–533. (Classic psychology study proposing TAP: memory success depends on the match between learning and retrieval conditions, a concept applied to SLA by Lightbown 2008 and others.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.