1. Introduction

In this article I take on the complex task of illustrating the cognitive processes that take place in the brain of a second language student writer as s/he produces an essay. Why? Because often, as teachers and target language experts, we forget how challenging it is for our students to write an essay in a foreign language. Gaining a better grasp of the thinking processes essay writing in a second language involves, may help teachers become more cognitively empathetic towards their students; moreover, they may reconsider the way they teach writing and treat student errors.

A caveat before we proceed: this article is quite a challenging read which may require some background in applied linguistics and/or cognitive psychology. However, if you want to avoid the complex stuff and concentrate on writing at lower proficiency levels (KS2 to KS4) you can go straight to section 3 below.

2. A Cognitive account of the writing processes: the Flower and Hayes (1981) model

The Flower and Hayes (1981) model of essay writing in a first language is regarded as one of the most effective accounts of writing available to-date (Eysenck and Keane, 2010). As Figure 1 below shows, it posits three major components:

- Task-environment,

- Writer’s Long-Term Memory,

- Writing process.

Figure 1: The Flower and Hayes model (click to expand)

The Task-environment includes: (1) the Writing Assignment (the topic, the target audience, and motivational factors) and the text; (2) the Writer’s Long-term memory, which provides factual knowledge and skill/genre specific procedures; (3) the Writing Process, which consists of the three sub-processes of Planning, Translating and Reviewing.

The Planning process sets goals based on information drawn from the Task-environment and Long-Term Memory (LTM). Once these have been established, a writing plan is developed to achieve those goals. More specifically, the Generating sub-process retrieves information from LTM through an associative chain in which each item of information or concept retrieved functions as a cue to retrieve the next item of information and so forth.The Organising sub-process selects the most relevant items of information retrieved and organizes them into a coherent writing plan. Finally, the Goal-setting sub-process sets rules (e.g. ‘keep it simple’) that will be applied in the Editing process. The second process, Translating, transforms the information retrieved from LTM into language. This is necessary, since concepts are stored in LTM in the form of Propositions (‘concepts’/ ‘imagery’), not words. Flower and Hayes (1980) provide the following examples of what propositions involve:

[(Concept A) (Relation B) (Concept C)]

or

{Concept D) (Attribute E)], etc.

Finally, the Reviewing processes of Reading and Editing have the function of enhancing the quality of the output. The Editing process checks that grammar rules and discourse conventions are not being flouted, looks for semantic inaccuracies and evaluates the text in the light of the writing goals. Editing has the form of a Production system with two IF- THEN conditions:

The first part specifies the kind of language to which the editing production

applies, e.g. formal sentences, notes, etc. The second is a fault detector for

such problems as grammatical errors, incorrect words, and missing context.

(Flower and Hayes, 1981: 17)

In other words, when the conditions of a Production are met, e.g. a wrong word ending is detected, an action is triggered for fixing the problem. For example:

CONDITION 1: (formal sentence) first letter of sentence lower case

CONDITION 2: change first letter to upper case

(Flower and Hayes, 1981: 17)

Two important features of the Editing process are: (1) it is triggered automatically whenever the conditions of an Editing Production are met; (2) it may interrupt any other ongoing process. Editing is regulated by an attentional system called The Monitor. Hayes and Flower do not provide a detailed account of how it operates. Differently from Krashen’s (1977) Monitor, a control system used solely for editing, Hayes and Flower’s (1980) device operates at all levels of production orchestrating the activation of the various sub-processes. This allows Hayes and Flower to account for two phenomena they observed. Firstly, the Editing and the Generating processes can cut across other processes. Secondly, the existence of the Monitor enables the system to be flexible in the application of goal-setting rules, in that through the Monitor any other processes can be triggered. This flexibility allows for the recursiveness of the writing process.

Hayes and Flower’s model is useful in providing teachers with a framework for understanding the many demands that essay writing poses on students. In particular, it helps teachers understand how the recursiveness of the writing process may cause those demands to interfere with each other causing cognitive overload and error.

Furthermore, by conceptualising editing as a process that can interrupt writing at any moment, the model has a very important implication for a theory of error: self-correctable errors occurring at any level of written production are not always the result of a retrieval failure; they may also be interpreted as caused by detection failure (failure to ‘spot’ a mistake).

One limitation of the model for a theory of error is that its description of the Translating and Editing sub-processes is too general. I shall therefore supplement it with Cooper and Matsuhashi’s (1983) list of writing plans and decisions along with findings from other L1-writing Cognitive research, which will provide the reader with a more detailed account. I shall also briefly discuss some findings from proofreading research which may help explain some of the problems encountered by L2-student writers during the Editing process.

3. The translating sub-processes

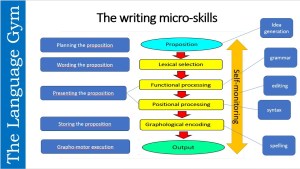

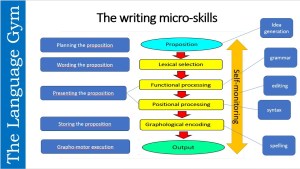

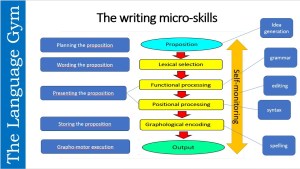

Cooper and Matsuhashi (1983) posit four stages, which correspond to Flower and Hayes’ (1981) conceptualization of the Translating process: Wording, Presenting, Storing and Transcribing (see picture 2 below)

Figure 2 – The Translating sub-processes (Click to expand)

- WORDING THE PROPOSITION (Lexical selection) – In this first stage, the brain transforms the propositional content into lexis. Although at this stage the pre-lexical decisions the writer made at earlier stages and the preceding discourse limit lexical choice, Wording the proposition is still a complex task: ‘the choice seems infinite, especially when we begin considering all the possibilities for modifying or qualifying the main verb and the agentive and affected nouns’ (Cooper and Matsuhashi, 1983: 32). Once s/he has selected the lexical items, the writer has to tackle the task of Presenting the proposition in standard written language.

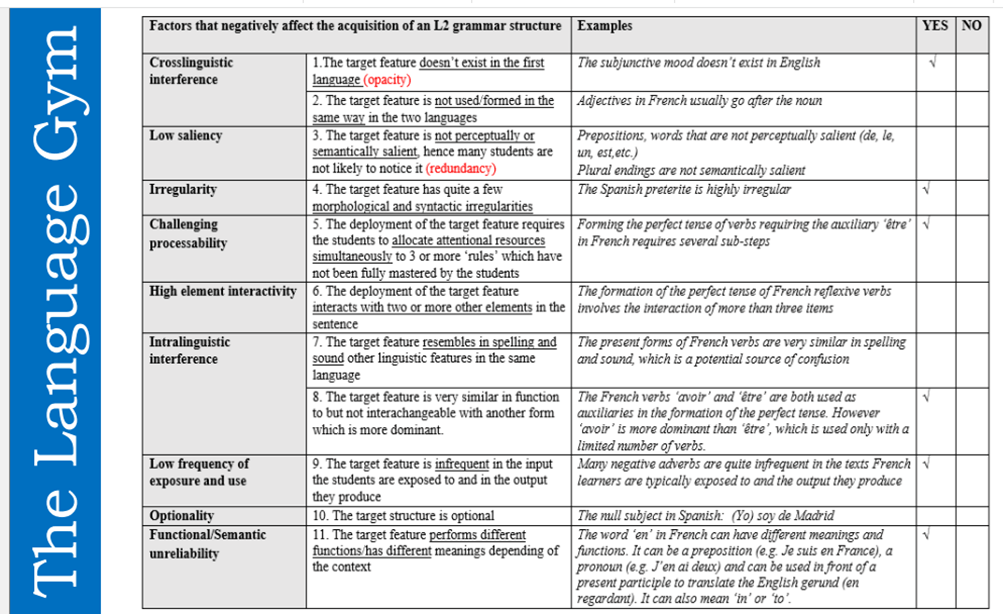

- PRESENTING THE PROPOSITION (Grammatical encoding) – This involves making a series of decisions in the areas of genre, grammar and syntax. In the area of grammar, Agreement, Word-order and Tense will be the main issues for L1_English learners of languages like French, German, Italian or Spanish. Functional processing, i.e. assigning a functional role (e.g. subject, verb, direct or indirect object) to every word in a sentence, precedes Positional processing, i.e. arranging the words in the correct syntactic order. This is the stage where grammatical mistakes are made, mostly due, in second language writing, to processing inefficiency (e.g. mistakes caused by cognitive overload), carelessness (i.e. superficial self-monitoring) and, of course, L1/L3 negative transfer (i.e. the influence of the first language or other languages).

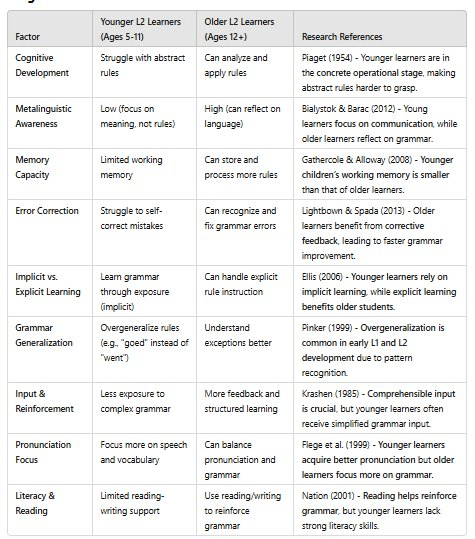

- STORING THE PROPOSITION (Phonological and Orthographic encoding) – The proposition, as planned so far, is then temporarily stored in Working Short Term Memory (henceforth WSTM) while Transcribing takes place, first in form of sound (phonological encoding). Phonological encoding is crucial for internal speech monitoring and for preparing the sentence for written output Propositions longer than just a few words will have to be rehearsed and re-rehearsed in WSTM for parts of it not to be lost before the transcription is complete. The limitations of WSTM create serious disadvantages for unpractised writers. Until they gain some confidence and fluency with spelling, their WSTM may have to be loaded up with letter sequences of single words or with only 2 or 3 words (Hotopf, 1980). This not only slows down the writing process, but it also means that all other planning must be suspended during the transcriptions of short letter or word sequences. This is where many spelling mistakes occur, especially with younger L2 learners (who have a much more limited working memory capacity than older learners) or less able older learners. This problem will be exacerbated in the case of children having to learn a completely different writing system (i.e. an English native learning to write in Mandarin).

- TRANSCRIBING THE PROPOSITION (Motor planning and execution) – The physical act of transcribing the fully formed proposition begins once the graphic image of the output has been stored in WSTM. In L1-writing, transcription occupies subsidiary awareness, enabling the writer to use focal awareness for other plans and decisions. In practised writers, transcription of certain words and sentences can be so automatic as to permit planning the next proposition while one is still transcribing the previous one. An interesting finding with regards to these final stages of written production comes from Bereiter, Fire and Gartshore (1979) who investigated L1-writers aged 10-12. They identified several discrepancies between learners’ forecasts in think-aloud and their actual writing. 78 % of such discrepancies involved stylistic variations. Notably, in 17% of the forecasts, significant words were uttered in forecasts which did not appear in the writing. In about half of these cases the result was a syntactic flaw (e.g. the forecasted phrase ‘on the way to school’ was written ‘on the to school’). Bereiter and Scardamalia (1987) believe that lapses of this kind indicate that language is lost somewhere between storage in WSTM and grapho-motor execution. These lapses, they also assert, cannot be described as ‘forgetting what one was going to say’ since almost every omission was reported on recall: in the case of ‘on the to school’, for example, the author not only intended to write ‘on the way’ but claimed later to have written it. In their view, this is caused by interference from the attentional demands of the mechanics of writing (spelling, capitalization, etc.), the underlying psychological premise being that a writer has a limited amount of attention to allocate and that whatever is taken up with the lower level demands of written language must be taken from something else.

In sum, Cooper and Matsuhashi (1983) posit four main stages in the conversion of the preverbal message into a speech plan: (1) the selection of the right lexical units (2) the application of grammatical and syntactic rules. (3) The unit of language is then deposited in WSTM in phonological and orthographic form, awaiting translation into grapho-motor execution (the physical act of writing). (4) grapho-motor execution

The temporary storage in stage (3) raises the possibility that lower level demands affect production as follows: (1) causing the writer to omit material during grapho-motor execution; (2) leading to forgetting higher-level decisions already made. Interference resulting in WSTM loss can also be caused by lack of monitoring of the written output due to devoting conscious attention entirely to planning ahead, while leaving the process of transcription to run ‘on automatic’.

Picture 2 (repeated)

Implications for teaching

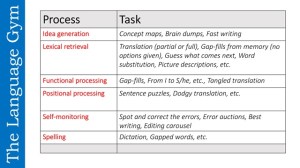

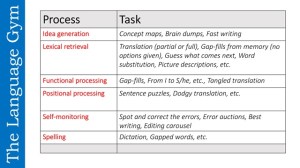

The implications of the above for second language instruction are obvious: the implementation of a process-based approach to writing instruction in which the teachers stages sequences of activities which explicitly address the micro-skills of writing. This entails engaging students, consistently, in tasks which practise said micro-skills. See picture 2 above, Picture 3 below, provides examples of activities that could be implemented for each micro-skill.

Imagine, after exploiting 90-95% comprehensible-input texts intensively through a range of activities, engaging the students in micro-writing tasks addressing all of the micro-skills of writing prior to staging more unstructured and creative activities. Would your students not perform better? Would you not be more inclusive?

4. How about editing? Some insights from proofreading research

Proofreading theories and research provide us with the following important insights in the mechanisms that regulate essay editing. Firstly, proofreading involves different processes from reading: when one proofreads a passage, one is generally looking for misspellings, words that might have been omitted or repeated, typographical mistakes, etc., and as a result, comprehension is not the goal. When one is reading a text, on the other hand, one’s primary goal is comprehension. Thus, reading involves construction of meaning, while proofreading involves visual search. For this reason, in reading, short function words, not being semantically salient, are not fixated (Paap, Newsome, McDonald and Schvaneveldt, 1982). Consequently, errors on such words are less likely to be spotted when one is editing a text concentrating mostly on its meaning than when one is focusing one’s attention on the text as part of a proofreading task (Haber and Schindler, 1981). Errors are likely to decrease even further when the proofreader is forced to fixate on every single function word in isolation (Haber and Schindler, 1981).

It should also be noted that some proofreader’s errors appear to be due to acoustic coding. This refers to the phenomenon whereby the way a proofreader pronounces a word/diphthong/letter influences his/her detection of an error. For example, if an English learner of L2-Italian pronounces the ‘e’ in the singular noun ‘stazione’ (= train station) as [i] instead of [e], s/he will find it difficult to differentiate it from the plural ‘stazioni’ (= train stations). This may impinge on her/his ability to spot errors with that word involving the use of the singular for the plural and vice versa.

Implications for teaching

The implications for language learning are that learners may have to be trained to edit their essays at least once focusing exclusively on form. Ideally, with beginner learners, the teacher should encourage several rounds of editing, each focusing on a different potential problem areas, gradually moving from easier to more challenging items.

Secondly, they should be told to pay particular attention to those words (e.g. function words) and parts of words (e.g. verb endings) which are not semantically and perceptually salient and are therefore less likely to be noticed.

Thirdly, dictations should feature regularly in language lessons from very early on in the L2 learning process, beginning with micro-dictation focusing on single letters or syllables, then moving on to gapped sentences and finally to longer texts with more cognitive challenging tasks such as dictogloss.

5. Bilingual written production: adapting the first language model

Writing, although slower than speaking, is still processed at enormous speed in mature native speakers’ WSTM. The processing time required by a writer will be greater in the L2 than in the L1 and will increase at lower levels of proficiency: at the Wording stage, more time will be needed to match non-proceduralized lexical materials to propositions; at the Presenting stage, more time will be needed to select and retrieve the right grammatical form. Furthermore, more attentional effort will be required in rehearsing the sentence plans in WSTM; in fact, just like Hotopf’s (1980) young L1-writers, non- proficient L2-learners may be able to store in WSTM only two or three words at a time. This has implications for Agreement in Italian, French or Spanish in view of the fact that words more than three-four words distant from one another may still have to agree in gender and number. Finally, in the Transcribing phase, the retrieval of spelling and other aspects of the writing mechanics will take up more WSTM focal awareness.

Monitoring too will require more conscious effort, increasing the chances of Short-term Memory loss. This is more likely to happen with less expert learners: the attentional system having to monitor levels of language that in the mature L1-speaker are normally automatized, it will not have enough channel capacity available, at the point of utterance, to cope with lexical/grammatical items that have not yet been proceduralised. This also implies that Editing is likely to be more recursive than in L1-writing, interrupting other writing processes more often, with consequences for the higher meta-components. In view of the attentional demands posed by L2-writing, the interference caused by planning ahead will also be more likely to occur, giving rise to processing failure. Processing failure/WSTM loss may also be caused by the L2-writer pausing to consult dictionaries or other resources to fill gaps in their L2-knowledge while rehearsing the incomplete sentence plan in WSTM. In fact, research indicates that although, in general terms, composing patterns (sequences of writing behaviours) are similar in L1s and L2s there are some important differences.

In his seminal review of the L1/L2-writing literature, Silva (1993) identified a number of discrepancies between L1- and L2-composing. Firstly, L2-composing was clearly more difficult. More specifically, the Transcribing phase was more laborious, less fluent, and less productive. Also, L2-writers spent more time referring back to an outline or prompt and consulting dictionaries. They also experienced more problems in selecting the appropriate vocabulary. Furthermore, L2-writers paused more frequently and for longer time, which resulted in L2-writing occurring at a slower rate. As far as Reviewing is concerned, Silva (1993) found evidence in the literature that in L2-writing there is usually less re-reading of and reflecting on written texts. He also reported evidence suggesting that L2-writers revise more, before and while drafting, and in between drafts. However, this revision was more problematic and more of a preoccupation. There also appears to be less auditory monitoring in the L2 and L2-revision seems to focus more on grammar and less on mechanics, particularly spelling. Finally, the text features of L2-written texts provide strong evidence suggesting that L2-writing is a less fluent process involving more errors and producing – at least in terms of the judgements of native English speakers – less effective texts.

Implications for teaching

Firstly, the process of writing being much more challenging in the second language, teachers must scaffold writing much more carefully. This starts with staging an intensive reading-to-learn phase prior to engaging the students in writing tasks, which unfortunately doesn’t happen with textbooks, because the latter only include reading-to-comprehend activities. After this intensive receptive phase, teachers should engage the students in a series of micro-writing tasks which gradually phase out support and increase in cognitive load. This means beginning writing practice with basic SVO sentences and gradually moving to more complex SVOCA sentence structures and subordination.

6. Conclusions

Essay writing is a very complex process which poses a huge cognitive load onto the average second language learner’s brain, especially at lower levels of proficiency. The cognitive load is determined by the fact that the L2 student writer has to plan the essay whilst focusing on the act of translating ideas (propositions) into the foreign language. Converting propositions into L2 sentences, as I have tried to illustrate, is hugely challenging per se for a non-native speaker, let alone when the brain has to hold in Working Memory the ideas one intends to convey at the same time. Working Memory being limited in capacity it is easy to ‘lose’ one or the other in the process and equally easy to make mistakes, as the monitor (i.e. the error detecting system in our brain) receives less activation due to cognitive overload.

Hence, before plunging our students into essay writing teachers need to ensure that they provide lots of practice in the execution of the different sets of skills that writing involves (e.g. ideas generation, planning, organization, self-monitoring) separately. For instance, a writing lesson may involve sections where the students are focused on discrete sets of higher order skills (e.g. practising idea generation; evaluating relevance of the ideas generated to a given topic/essay title) and sections where lower order skills are drilled in ( application of grammar and syntax rules, lexical recall, spelling). Only when the students have reached a reasonable level of maturity across most of the key skills embedded in the models discussed above should students be asked to engage in extensive writing.

Consequently, an effective essay-writing instruction curriculum must identify the main skills involved in the writing process (as per the above model); allocate sufficient time for their extensive practice as contextualized within the themes and text genres relevant to the course under study; build in the higher order skill practice opportunities to embed practice in the lower order skills identified above (the mechanics of the language), whilst being mindful of potential cognitive overload issues.

In terms of editing, the above discussion has enormous implications as it suggests that teachers should train learners to become more effective editors through regular editing practice (e.g. ‘Error hunting’ activities). Such training may result in more rapid and effective application of editing skills in real operating conditions as the execution of Self-Monitoring will require less cognitive space in Working Memory. Training learners in editing should be a regular occurrence in lessons if we want it to actually work; also, it should be contextualized in a relevant linguistic environment as much as possible (e.g. if we are training the students to become better essay editors we ought to provide them with essay-editing practice, not just with random and uncontextualized sentences).

In conclusion, I firmly believe that the above model should be used by every language teacher, curriculum designer as a starting point for the planning of any writing instruction program. Not long ago I took part in a conference and a colleague was recommending to the attending teachers to give his Year 12 students exam-like discursive essays to write, week in week out for the very first week of the course. I am not ashamed to admit that I used to do the same in my first years of teaching A levels. The above discussion, however, would suggest that such an approach may be counterproductive; it may lead to errors, fossilization of those errors, and inhibit proficiency development whilst stifling the higher metacomponents of the writing process, idea-generation, essay organization and self-monitoring.

You must be logged in to post a comment.