INTRODUCTION

ICT integration in the MFL curriculum and its implementation in the classroom pose a series of important challenges which refer to the way digital tools and tasks affect language acquisition as well as the students’ general cognitive, emotional, social and moral development.

Unfortunately, not much is known about the impact of digital assisted teaching and learning on language acquisition and I am not aware of any research-based approaches to ICT integration in MFL. Teachers apply their intuitions and experience accumulated through non-digital assisted teaching to emerging technologies often taking a leap of faith.

In what follows I advocate a more systematic, thorough and reflective approach to ICT integration in MFL teaching and learning, one which considers cognitive, ethical, pragmatic and, of course, pedagogical factors. I also advocate, that whilst I believe that emerging technologies can indeed enhance learning, they will not unless they are effectively harnessed. This requires (a) an understanding of language acquisition; (b) a grasp of how each digital medium affects acquisition; (c) how it fits an individual teacher’s ecosystem.

TWELVE CHALLENGES OF ICT INTEGRATION IN MFL

Please note that the list below is not exhaustive; it only includes what I deem to be the most important challenges I have identified based on my own experiences with ICT integration.

Challenge 1: Enhancement power vs Integrating ICT for ICT integration’s sake

The first question you have to ask yourself when planning to use an app or web-tool or carrying out any digitally-based task in your lessons is: Does it really enhance teaching and learning as compared to my usual non-ICT based approaches? How can I be sure of that?

Teachers often feel compelled to use an app or web-tool for fear of not appearing innovative enough in the eyes of their managers; however, after all, if their classroom presence, charisma, humour, drama techniques, etc. are more compelling than Kahoot, iMovies, Tellagami and the likes, it would be silly to use less impactful teaching tools just to check the ICT-integration box – unless, of course, one is doing it for the sake of variety or to get some rest at the end of a long and tiring school day.

In my experience this is one of the most difficult challenges when a school goes 1:1 with lap-tops or tablets. Teachers feel that if they do not use ICT as much as possible they are somehow failing the school or will be left behind. This can cause some teachers, especially the less ICT-savvy ones, serious anxiety. And if this issue is not properly tackled from the beginning, learning will be affected quite negatively, especially during the first phase of integration when teachers are trying things out.

Possible solutions

This issue can be addressed by:

- Providing training in how specific digital tools and tasks actually affect student cognition and language acquisition at different stages of MFL proficiency developments. Emerging technologies workshop facilitators and ICT integration coaches usually show teachers how to use a specific tool or conduct an ICT-based task but do not delve into how it enhances language acquisition across the four macro-skills and why it is superior to its non-digital counterpart. To buy into ICT integration in MFL, teachers must be provided with a solid rationale as to why, how and when in a teaching sequence specific digital tools and tasks enhance learning. This is rarely done. Experimentation with a digital tool at the expenses of student learning is ethically wrong considering that little teacher contact time is usually available to MFL learners.

- Deciding on a set of clear pedagogic guidelines, both generic and subject-specific, for ICT integration in lessons (e.g. Generic guidelines such as: Is there an expectation for the iPad to be used in every single lesson? ; MFL specific guidelines: When doing a project about school, students should not do the filming around school during lesson time). Whilst the provision of an overly prescriptive framework would impact teaching and learning negatively, in my view, a clearly laid out pedagogic framework for ICT integration would prevent some teachers from over-using digital tools and others from under-using them. The elected framework will have to be convergent with the MFL department’s espoused methodological approach to language instruction.

- Producing an MFL-department ‘ICT handbook’ detailing the benefits and drawbacks of each digital tools and embed in curriculum design–This would complement the above-envisaged guidelines. The ‘handbook’ could take the form of an interactive google sheet onto which each member of the MFL team logs in the pros and cons for learning of each digital tool as their understanding of its impact on learner cognition increases. Unlike what often happens this should not merely consist of a dry detailed list of the latest and coolest apps with technical tips and a cryptic description like “Good for listening” or “Children find it fun”. After the first ICT integration cycle, embed the best recommendations found in the ‘handbook’ in your schemes of work.

- Piloting the digital tools prior to use –Get a few students – including ‘weaker’ students, too – to try the app or website at lunchtime or after school, possibly in your presence; if not possible, ask them to do it at home. Then gather some feedback on it about the ‘mechanics’, how much they learnt, how enjoyable they found it, how they would improve it. Remember to ask them to compare the impact of that app with the non-digital approaches to the same tasks that you would normally use. Piloting digital apps and tasks has been a lifesaver for me on several occasions.

- Student voice – see below (Challenge 5)

Challenge 2 – Language learning metaphors we live by

Digital literacy within and without the language learning domain is very important. So are E-learning strategies (i.e. the set of approaches and techniques which MFL students can deploy in order to independently use web-based resources to enhance their learning). However, if, as part of our teaching philosophy, we set out to forge effective lifelong language learning habits with our students we also have the ethical imperative to impress on them the importance of human-to-human interaction as a fundamental lifelong learning skills. As discussed in a previous post (‘Rescuing the neglected skill’), ICT integration in MFL often results in oral proficiency and particularly fluency (the proceduralization of speaking performance) being neglected. This is usually due to a tendency to involve students in (a) ludic activities (e.g. online games of low surrender value); (b) the creation of digital artefacts through single or multiple apps; (c) digitally-assisted projects of the likes envisaged by Puentedura’s Redefinition criteria.

By skewing the classroom language acquisition process towards an interaction-poor and mainly digitally-based model of learning we give rise to metaphors of learning which do not necessarily truly reflect the way language is produced and learnt in the real world. These metaphors – rightly or wrongly – may form the core of our students’ beliefs as to how languages are learnt for the rest of their lives!

Possible solutions

Teachers ought to ensure that there is a balanced mix of digital and non-digital tasks and that oral activities aimed at developing oral competence and involving learner-to-learner interaction feature regularly in MFL lessons. After all, we want to forge students who can interact with other humans, don’t we?

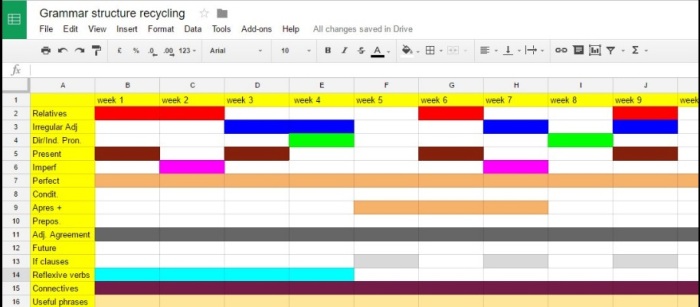

Challenge 3 – Curricular unbalance

As mentioned above, ICT MFL integration has the potential to be detrimental to oral fluency development. In my experience, however, other aspects of language acquisition are penalized too; one is listening fluency and another one is grammar proceduralization. As far as listening goes, one reason is that there are not very many free apps and web-based resources which promote aural skills. Another issue relates to the fact that one very important aspect of listening competence, listenership, is often overlooked in the ‘techy’ classroom. Listenership refers to the ability to listen, comprehend and respond as part of an interaction with an interlocutor; when learners work with a machine, there is no interlocutor to react to…

As for grammar, there are verb conjugators like mine (www.language-gym.com) and apps and websites involving work on morphology and syntax; but these are not designed to develop cognitive control over the target grammar structures (i.e. accurate written or oral performance under real operating conditions).

Language and communicative functions (e.g. agreeing and disagreeing; sequencing information; comparing and contrasting) are also often neglected in digitally-based PBL.

Possible solutions

Ensure that in every unit in your schemes of work ICT-based integration does not result in an excessive focus on reading, writing, word-level vocabulary learning and grammatical drills of the gap-filling/mechanical kind.

Challenge 4 – Divided attention

Unless students are highly proficient in the target language, digital manipulation has the potential to hijack student attention away from language learning. Cutting, pasting, app-smashing, searching for sound-effects, downloading images, etc. take up a lot of the students’ cognitive resources. My students also often complain about being distracted by the notifications they get from e-mail and social network whilst on task. The obvious consequence is divided attention which may lead to poor retention.

Another source of divided attention is the cue-poor nature of digital media. In a typical interaction with a teacher or peer an MFL student can rely on many verbal and non-verbal cues (e.g. facial expressions and gestures) which will enhance understanding or clarify any doubts s/he may have; however, when it comes to digital environments, apps or web-tools are not as cue-rich and may pose various challenges that may disorientate less ICT-savvy or confident learners. If one has twenty or more students, it is not rare to have two or three experiencing this sort of problem at the same time. Hence, yet another source of divided attention.

Possible solutions

First and foremost, get your students to turn off social networks and social network notification and establish some clear sanctions for those who do not.

Do not involve students in any digital manipulation in lesson unless absolutely necessary. Flip it: get it done at home!

Model the use of an app / web-tool to death, until you are 100% sure everyone has understood how to use it. Also, group the less ICT-savvy students together – you will spot them very soon, trust me. This will save you the hassle of running from one side to the other of the classroom and will avoid other students being distracted by requests for help coming from those very students.

Challenge 5 – Time-cost

This point follows on from the previous one, in that, in view of the very little teacher contact time available to MFL teaching, one has to put every single minute available to very good use; to invest a lot of valuable lesson time into the mechanical manipulation of a digital tool which does not directly contribute to language acquisition verges on the unethical considering that the ultimate objective of language learning is to automatize receptive and productive skills – which requires tons of practice.

Possible solutions

The same provided for the previous point.

Challenge 6 – Variety

I have observed many ‘techy’ lessons where students spend a whole hour on the iPad! This practice is counter-productive not only for what I have discussed above, but also because there is research evidence that many students do find it tedious and not conducive to learning (Seymour,2015). In a small survey I carried out some time ago, my students recommended that the continued use of the iPad should last no longer than 15-20 minutes.

Possible solutions

Even though you may change app or game or task, you cannot keep your students on the iPad, laptop or whatever device you use for a whole lessons! As discussed in a previous post, it is good practice to alternate short and long focus, individual and group work, digital and non-digital tools/tasks, receptive and productive skills, ludic and academic activities, etc.

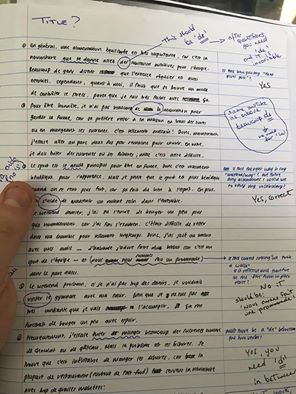

Challenge 7 – Student voice – How do we get the information ?

At some point you will want to find out how ICT integration into your teaching eco-system is being perceived by your students. Many education providers will go about it by administering questionnaires, possibly a google form as it is easy to set up, administer and analyze quantitavely. However, there are many problems with that if you want to obtain rich data which will help you improve the next cycle of ICT integration. The main problem is that a typical google-form survey ‘imposes’ onto the informants closed questions which require them to answer by choosing yes or no, or a frequency (e.g. often, rarely) or quantity (e.g. a lot, some) adverb. However, say 30 % of the students indicate they do not find ICT useful; you will not know why and which aspects they are referring to. Not to mention the fact that this kind of data elicitation encourages a very superficial ‘tick the box’ approach which does not spark off deep thinking on the issues-in-hand.

Hence, to enhance the richness of the data so obtained, course administrators ought to at least triangulate the google surveys with one-on-one semi-structured interviews involving a cross-section of learners of different ability and gender. A former colleague of mine, in her master’s dissertation research, found out that her interview findings on ICT integration often contradicted data on the same issues obtained through a google-form survey.

Challenge 8 – Evaluation of ICT integration by peers /SLT

In many schools ICT integration in MFL is evaluated by using the SAMR model. This can be detrimental to foreign language learning for reasons that I have discussed at length here: http://tinyurl.com/o3yp64v (Of SAMR and SAMRitans – Why the adoption of the SAMR model may be detrimental to foreign language learning)

Possible solution

See solution to challenge 1, above (point 2)

Challenge 9 – Learner attitudes towards digital tools

If your school has gone 1:1 with the iPad or other tablet you may find that in most of your classes there will be one or more students who will not enjoy using the device for language learning. This presents you with an ethical dilemma. If it is imperative to differentiate our teaching so as to cater for every learner’s cognitive and emotional needs what can you do to suit their learning preferences?

Possible solution

If, after trying various tactics, you still have not managed to ‘win the learner over’ and their aversion for the mobile device still remains, you have three options that I can think of. First one: tough, they need to adapt – not the most empathetic of approaches. Second option: give them alternative tasks with similar learning outcomes using traditional media. Third option: if you use the iPad for snappy activities of no more than 10-15 minutes alternated with other non-digitally-based tasks, as I do, you will find that these students will not complain much at all, in the end.

Challenge 10 – Lack of meta-digital language learning awareness

The internet offers a vast array of TL learning opportunities. However, students need to be equipped with the metacognitive tools which will enable them to seize those opportunities. This entails teaching learners how to learn from TL internet input sources, web-tools and App so as to be able to use them autonomously (e.g. how to best use verb conjugation trainers, Youtube, Memrise, Wordreference forums, etc. for independent learning ).

Possible solutions

Embed one or more explicit learner training program in meta-digital learning strategies (e.g. e-learning strategies) per ICT integration cycle. Since learner training programs do require extensive practice in the target strategies, one should offer instruction in only a limited range of strategies per cycle. A widely-used instructional framework can be found in this post of mine: http://tinyurl.com/qxafy7m (‘Learner training in the MFL classroom’)

Challenge 11 – Ethical issues

Easy access to the digital medium and apps entails the danger of ‘cut and paste’ plagiarism and the use of online translators.

Possible solution

Besides alerting the students to the dangers of such practices, teachers may ask their students to sign a ‘contract’ in which they pledge never to commit plagiarism nor to use online translators. During the initial phase of integration, teachers will have to remind students of their pledge to keep it into their focal awareness and spell out the sanctions for flouting the ‘rules’. In my experience this is a highly successful tactic to pre-empt such issues.

Challenge 12 – Product vs Process

Since a lot of apps and emerging technologies workshops concern themselves with the production of a digital artefact (e.g. iMovies) ICT integration in MFL is often characterized by an excessive concern with the product of learning. However, language teaching should focus mainly on the development of listening, speaking, reading and writing skills (the process of learning) rather than merely putting together a digital movie, app-smashing or presentation (the product).

Possible solution

The production of a digital artefact can be conducive to language acquisition if teachers and learners lay as much emphasis on the process of learning as they do on the final product. This involves identifying what levels of complexity and fluency in each macro-skill are expected of the learners at each stage in the development of a given project and provide extensive contextualised practice throughout the process with those aspirational levels in mind.

Conclusion

Successful ICT integration in the MFL curriculum and its practical implementation are no easy tasks. First and foremost they require a pedagogical framework which is consonant with whatever instructional approach to L2 learning is espoused by the MFL team. Secondly, its effectiveness will be a function of the extent to which a teacher knows how, why and when digital tools enhance learning and affect learner cognition and language acquisition. Thirdly, teachers need to control the tendency, common during the first cycle of integration for teachers to let the digital medium take over and drive teaching and learning; this is very common amongst emerging technologies enthusiasts. This is highly detrimental to learning and I have experienced first-hand the damage it causes to student enjoyment and motivation as well as to their levels of oral and aural fluency. Fourthly, learners’ meta-digital learning awareness and strategies need to be enhanced through structured learning-to-learn programs. Fifthly, teachers must not forget that they have the ethical imperative to form a balanced linguist versed in all four macro-skills and endowed with high levels of fluency and autonomous competence. ICT integration must be eclectic and mindful of this.

In conclusion, ICT integration in MFL is not an exact science as yet. For it to be successful, the best recipe is not to rush it for the fear of been ‘left behind’ and not appear as an ‘innovative’ school or teacher. Course administrators and teachers must always have at heart the linguistic, cognitive, socio-affective and moral needs of their students and integrate ICT with those needs in mind. Not merely integrate for integrations’ sake. Ultimately, ICT integration should assist, not drive, teaching and learning.

You must be logged in to post a comment.