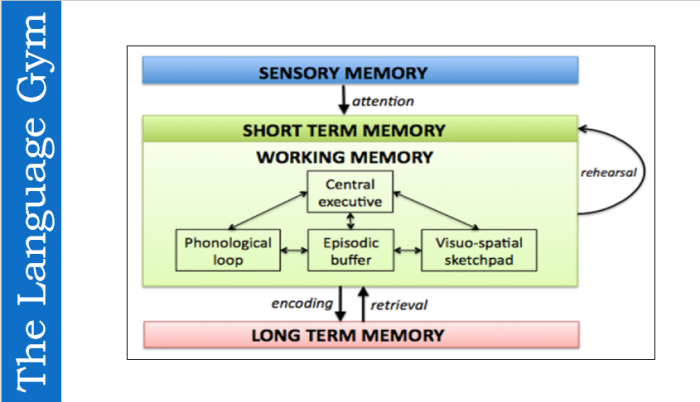

Fig. 1 – The most influential Skill-Theory account of language acquisition (Anderson, 1983)

1. Introduction

In a previous post, I argued that every language teacher, both novice and expert, should ask themselves the question “How do I believe that languages are learnt?” as a starting point for a deep and productive reflection on their own teaching practice.

The answer to that question is key, as without a clear and solid set of pedagogic principles our curriculum planning and design and every other decision that affects teaching and learning in our classroom will be random and haphazard or based on ‘hunches’. Imagine choosing a course-book, creating assessment procedures and materials, deciding to integrate Information Technology or Generic-skill learning in our teaching without having formed an opinion as to how languages are best taught and learnt? Would you believe me if I told you that I have seen this done, time and again, even in some of the best schools in the world?

As I suggested in that post, teachers and language departments should identify the set of pedagogic principles that truly constitute the tenets of their teaching philosophy and classroom approach and draw on them to ‘frame’ their long-, medium- and short-term planning, their discussions on teaching and learning (e.g. the ones that occur after a lesson observation), their assessment and any big decision of theirs that may significantly impact teaching and learning. Having such a framework will warrant coherence and fairness in peer and student assessment. It will also give the course administrators a better idea of what Modern Language (ML) teaching and learning is about in the institution they manage.

This is my own personal answer to the question “How do I believe that language are learnt?”, or rather part of it, as I will narrow the scope of this post only to the main tenets of my approach to ML teaching – borrowed from Skill Theory. Hence I will leave out other major influences on my personal pedagogy (e.g. Schmidt’s Noticing Hypothesis, Bandura’s Self-efficacy theory, Selinker’s Interlanguage hypothesis, MCcLelland and Rumelhart’s Connectionism, etc.).

2. My set of guiding principles

2.1 Skill Theory – the (very) bare bones

Whilst it integrates elements from several SLA theories, My approach is rooted in Cognitive-psychology-based accounts of instructed second language acquisition, especially what Applied Linguists call Skill Theory (as laid out in Anderson,1994; Johnson, 1996,; DeKeyser, 1998; Jensen, 2007). I underscored the word ‘instructed’ for a reason: I do not believe that Skill Theory provides an accurate account of how languages are learnt in naturalistic environments.

In a nutshell, Skill Theorists observe that every complex task humans learn is made up of several layers of sub-tasks. For instance, driving a car requires a driver to pay attention to the road and take important decisions as to where to turn, how fast to go, when to brake; however, whilst taking these decisions, the driver is carrying out multiple ‘lower-order’ tasks such as changing gear, physically pushing the brakes, operating the indicator, etc.

Skill theorists observe that lower-order tasks are performed subconsciously, without requiring the brain’s Working Memory to pay much conscious attention to them (or, as they say: they only occupy subsidiary awareness). This, in their view, points to an adaptive feature of the brain: in order to be able to solely focus on the most important aspect(s) of any complex tasks, the brain, throughout Evolution, has learnt to automatize the less complex tasks.

This is because, based on current models of Working Memory (e.g. Baddeley,1999) the brain has very little cognitive space to devote to any given task. For instance, when it comes to numbers, Working Memory channel capacity can only process 7+/- 2 digits at any one time Miller (1965). In simpler terms, the only way for the brain to effectively and efficiently mult-task, is to automatize sub-tasks which are less complex.

Fig. 2 – Working Memory as conceived by Baddeley (1999)

Skill Theorists argue that the same applies to language learning. A language learner needs to automatize lower order skills so as to be able to free up space in Working Memory in order to execute more complex tasks requiring the application of higher order skills. Example: you cannot form the perfect tense if you do not form the past participle of a verb and have not learnt the verb ‘to have’. Hence, the aim of language teaching is to train language learners to automatize the knowledge that the instructor provides explicitly to them (i.e. the knowledge of how a rule is formed). Once automatized, it will not require the brain’s conscious attention and the learner will have more space in their Working Memory to deal with the many demands that a language task poses to them.

Imagine having to produce a sentence and having to think simultaneously (in real time!) about the message you want to convey, the most suitable vocabulary to convey it through, tense, verb endings, word order, agreement, etc. an impossible task for a novice whose mistakes will be due mainly to (cognitive) overload). Such a task would be a fairly easy one for an advanced learner as s/he will have automatized most of the grammar- and syntax-related tasks and will only have to focus on the message and the lexical selection.

This automatization process is long and requires a greater focus on fluency, lots of scaffolding in the initial phase and negative feedback (correction) plays an important role.

A final point: Skill theorists (e.g. De Keyser 1998) propose that Communicative Language teaching which integrates explicit grammar instruction and focus on skill-automatization constitutes to date the most effective ML teaching methodology.

2.2 Skill-Theory principles and their implications for teaching and learning

2.2.1 Principle 1: language skills are acquired in the same way as any other human skill

The main point Skill-theory proponents make is that languages are learnt in much the same way as humans acquire any other skill (e.g. driving a car, cook, paint). This sets it apart from other influential schools of thoughts, which view language skills as a totally unique set of skills, whose functioning is regulated by innate mechanisms that formal instruction cannot impact (the so-called Mentalist approaches). This is a hugely important premise as it endorses what Applied Linguists call a strong interface position, i.e. the belief that whatever is learnt consciously (e.g. a grammar rule) can become automatized, i.e. executable subconsciously, through practice.

2.2.2 Principle 2: In instructional settings where the L2 grammar is taught explicitly, grammar acquisition involves the transformation of Declarative into Procedural knowledge

Whatever we learn is stored in the brain in one of two forms: (1) Declarative Knowledge, or the explicit knowledge of how things work and it is applied consciously (like knowing all the steps involved in the formation of the perfect tense) or (2) Procedural knowledge, the knowledge we acquire by doing and that we use to perform a specific task automatically, without thinking (like knowing how to ride a bike).

Example: I have declarative knowledge of the English perfect tense when I can explain the rule of its formation and application. I have procedural knowledge of it when I can use it without knowing the rule (e.g. because I have picked it up whilst listening to English songs or interacting with English native speakers).

Declarative knowledge has the advantage of having generative power, e.g.: if I learn the rule of perfect tense formation for French regular verbs I will be able to apply it to every single regular verb I come across. On the other hand, Procedural knowledge is limited only to the regular perfect forms I learn.

An advantage of Procedural Knowledge is that it is fast. So, a beginner who was taught ten perfect verb forms by rote learning can apply all of them instantly without thinking. Another beginner who was taught the rule of perfect tense formation, will have to apply each step of the rule one by one, which will slow down production.

According to Skill Theorists the aim of any skill instruction, including Modern Language teaching is to enable Declarative Knowledge to become Procedural (or Automatic). In the context of grammar learning, this means that a target rule which is initially applied slowly, step by step, occasionally referring to conjugation tables, will be applied – after much practice of the kind described in 2.2.6 below – instantly with little cost in terms of Working Memory processing efficiency.

It should be noted that our students pick up Procedural knowledge all the time in our lessons when we teach them unanalysed chunks such as classroom instructions or formulaic language. Whilst teaching such chunks should not be discouraged, Skill Theorists do believe that, in view of their limited generative power, instruction should not excessively rely on rote learning.

2.2.3 Principle 3: The human brain has limited cognitive space for processing language, so it automatizes lower order receptive and productive skills in order to free up space and facilitate performance

When we learn to drive, we need to learn basic skills such as how to switch on the engine, change gear, press the clutch, turn on the wipers, operate the brakes, etc. before we actually take to the road. Once the lower order operations and skills listed above have been automatized or at least routinized to the extent that we do not have to pay attention to them (by-pass Working Memory’s attentional systems), we can actually be safe in the assumption that we can wholly focus on the higher order skills which will allow us to take the split seconds decisions that will prevent us from getting lost, clash with other cars, break the traffic laws whilst dealing with our children messing about in the back seats.

This is what the brain does, too, when learning languages. Because Working Memory has a very limited space available when executing any task, the brain has learnt to automatize lower order skills so that, by being performed ‘subconsciously’ they free up cognitive space. So, for instance, if I am an advanced L2 speaker who has routinized accurate L2 pronunciation, grammar and syntax to a fairly high degree , I will be able to devote more conscious attention (Working Memory space) to the message I want to put across. On the other hand, if I still struggle with pronunciation, word order, irregular verb forms and sequencing tenses most of my attention will be taken up by the mechanics of what I want to say, rather than the meaning; this will slow me down and limit my ability to think through what I want to say due to cognitive overload.

In language teaching this important principle translates as follows: in order to enable our students to focus on the higher order skills involved in L2 comprehension and production we need to ensure that the lower-order ones have been acquired or performance will be impaired. Here are a few scenarios which illustrate what I mean.

Example 1: a student who struggles with pronunciation and decoding skills in English (i.e. being able to match letters and combinations of letters with the way they are sounded) will find it difficult to comprehend aural input from an English native speaker as they will not be able to identify the words they hear with the phonological representation they have stored in their brain. Hence, listening instruction ought to concern itself with automatizing those skills first (read here why and how).

Example 2: for a student who has not routinised Masculine, Feminine and Neuter endings in German, applying the rules of agreement in real time talk will be a nightmare. The same student will take for ever to write a sentence containing a few adjectives and nouns because his brain’s (working memory’s) capacity will be taken up by decisions such as what agrees with what, what the correct ending is and what the word order is; by having to deal with these lower order decision s/he will lose track of the higher order issue: to generate a meaningful and intelligible sentence

Example 3: if you teach long words (e.g. containing three syllables or more) to a beginner who has not automatized the pronunciation of basic target language phonemes, his Working Memory will struggle to process it (because of Phonological Loop overload), which will impair rehearsal and its commitment to Long-Term Memory.

Example 4: you cannot hope for a student of French or Italian to be able to acquire the Perfect tense if they have not automatized the formation of the verbs ‘to be’ and ‘to have’ and of the Past Participle. Yet, often we require our students to produce under time constraints Perfect tense forms a few minutes after modelling the formation of the Past Participle.

Hence, teaching ought to focus much more than it currently does, on the automatization of lower order skills (or micro-skills as we may also call them) across all four language skills . In this sense, progression within a lesson should mainly refer to the ability of our students to produce the target L2 item with greater ease, speed and accuracy (horizontal progression), rather than moving from a level of grammar complexity to a higher one, from using two adjectives in a sentence to using five or from using only one tense to using three (vertical progression).

The progression I believe teachers should prioritize is of the horizontal kind. We should concern ourselves with vertical progression only if and when horizontal progression has achieved automatization of the target L2 item.

Most of the failures our students experience in our lessons is due to focusing on vertical progression to soon, mostly because of teachers’ rush to cover the syllabus and/or ineffective recycling.

2.2.4 Principle 4: Acquisiton is a long pain-staking process whose end-result is highly-routinized consistently- accurate performance (which approximates, rarely matches native-speaker performance)

Automatization is a very long process. Think about a sport, hobby or other activity you excel at. How long it took you to get there. How much practice, how many mistakes, how much focus. Every skill takes huge amounts of practice in order for it to be automatized, lower order skills usually taking less time than higher order ones as they require simpler cognitive operations (there are exceptions though, e.g., in language learning, the acquisition of rules governing items which are not salient such as articled prepositions in French, Spanish or Italian).

The process is long for a reason; whenever a given L2 grammar rule is fully acquired, it gives rise to a cognitive structure (called by Anderson,2000, a ‘production’) which can never be modified. As a result, the brain is very cautious and requires a lot of evidence that whatever rule we apply in our performance is correct. Hence we need to use a specific grammar rule lots of times and receive lots of positive feedback on it, before a permanent production is formed and incorporated.

Do not forget, also, that when a learner is figuring out if their grasp and usage of a given L2 grammar rule is correct s/he might have two or even more possible hypotheses about how it may work and try them concurrently, awaiting positive or negative feedback to confirm or discard them. Hence, the brain needs to make sure that one of the hypotheses it is testing about how a given language item works ‘prevails’ so to speak over the others substantially before ‘accepting’ to incorporate it as a permanent structure. In the absence of negative feedback – hence the importance of correction, especially in the initial stages of instruction – the brain might store more than one form.

Example: a student keeps using (1) ‘j’ai allé’ and (2) ‘je suis allé’ alternatively to mean ‘I went’ in French ; if he does not heed or receive regular corrective feedback pointing to (2) as the correct one and does not use (2) in speaking and writing often enough to routinize it, (1) and (2) will still compete for retrieval in his brain.

2.2.5 Principle 5 : the extent to which an item is acquired depends largely on the range and frequency of its application (i.e. across how many context I can use it accurately and automatically)

A tennis player being able to perform a back-hand shot only from one specific point of the tennis court cannot be said to have acquired mastery of back-hand shooting. Evidently, the more varied and complex the linguistic and semantic contexts I can successfully apply a given grammar rule and vocabulary in, the greater will be the extent of its acquisition.

Example: whilst learning the topic ‘animals’ student X has practised over and over again the word ‘dog’ for three weeks only in the contexts ‘I have a dog’,’ my dog is called rex’, ‘Mark has a dog’, ‘I like dogs because they are cute and playful’, ‘we have a dog in the house’. Student Y, on the other hand, has been given plenty of opportunities to practise the word dog in associations with all the persons of the verb ‘to have’, with many more verbs (e.g. feed, groom, love, walk , etc.), with a wider range of adjectives new and old (good, bad, loyal, funny, lazy, grredy,etc.) and other nouns (I have a dog and a turtle, a dog and a cat, etc.). Student Y will have built a more wide-ranging and complex processing history for the word ‘dog’ which will warrant more neural associations in Long-term memory and, consequently greater chances of future recall and transferrability across semantic fields and linguistic contexts.

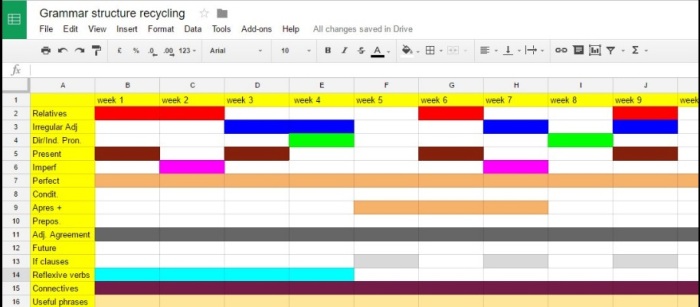

Consequently, language teachers must aim at recycling each core target item across as many linguistic and semantic contexts as possible. For instance, if I am teaching the perfect tense in term 3 and I have covered four different semantic areas prior to that, I would ensure that that tense is recycled across as many of those areas too. In a nutshell: the extent to which the target L2 items have been acquired by our students will be largely a function of their processing history with those items.

In concusion, the more limited the input we provide them with and the output we demand of them the less deeply we are likely to impact their learning.

2.2.6 Principle 6: Acquisition is about learning to comprehend and produce language faster under Real Operating Conditions

The five principles laid out above entail that for language acquisition to occur, effective teaching must aim at enabling the learners to understand and produce language under real life conditions or, as Skill-Theorists say ‘Real Operating Conditions’ (ROC). This changes the focus of instruction from simply passing the knowledge of how grammar works and what vocabulary means (Declarative Knowledge) to enabling students to apply it quickly and accurately (Procedural knowledge) by providing lots of training in fluency. Hence, for grammar to be acquired we must go beyond lengthy grammar explanations, gap-fill exercises and quizzes. E.g.: students must be asked to use the grammar in speaking and writing under time pressure.

Training students to be fluent across all four skills means scaffolding instruction much in the same way as one would do in tennis or football coaching. First, one would start by working on automatizing the micro-skills, as already discussed above. Secondly, one would focus on routinizing the higher-order skills by providing an initial highly structured support which is gradually phased out. This translates itself, in my classroom practice as follows:

(1) An initial highly controlled phase which includes: modelling, receptive processing and structured production– During this phase the target L2 item is practised in a controlled environment. The phase starts with lots of comprehensible input through the listening and written medium. The target grammar/vocabulary is recycled extensively before the students engage in production.

A structured production phase ensues. The input given and the output demanded are highly controlled and the chances of error are minimised by providing lots of scaffolding (e.g. vocab lists; grammar rule reminders; writing mats,dictionaries, etc.) and guidance and by imposing no time constraints. Example (speaking practice in the present tense ): highly structured role-play in the present tense only, where each student has to translate their respective lines from the L1 to the L2 or are given very clear L1 prompts; the language is simple and the students are very familiar with the verbs to be conjugated; verb tables are available on the desk.

(2) A semi-structured expansion phase –This phase is about consolidation and recycling and cuts across all the topics subsequently taught. So, for instance, if one has introduced the French negatives in Term 1 under the topic Leisure, they will recycle them throughout the subsequent terms as part of the topics taught in those terms until the teacher feels fit. This will ensure that the target structure/vocabulary is systematically recycled in combination with old and new.

During this phase, the support is gradually reduced. The input provided and the output expected are more challenging but the teacher still designs the activities with a specific set of vocabulary and grammar structures in mind. Some form of support still available. Example (speaking practice in the present tense): interview in the present tense across a range of familiar topics. Prompts for questions and answers are provided by the teacher (in the L1 or L2). The students are given some time to look at the prompts and think about the answers. Prompts look like this:

Partner 1: ask where Partner 2 usually goes at the week-end

Partner 2: answer providing three details of your choice relating to sport

This phase ends when the teacher feels the students can produce the target structure/vocabulary without support.

(3) An autonomous phase – Here the support is removed. Examples (speaking practice in the present tense): (1) Students are shown pictures and are recorded and assessed as they describe them. The task may elicit a degree of creativity and the use of communication strategies to make up for lack of vocabulary. (2) students are asked to have a conversation about the target topic with only a vague prompt as a cue (e.g. talk about your hobbies). They generate questions and answers impromptu under time constraints. Conversation is recorded and assessed.

(4) A routinization phase – in this phase, the only concern is speed of delivery. The teacher focuses on training the students to produce language ‘fast’, under R.O.C. (real operation conditions), i.e. real life conditions, across various topics and in spontaneous conversations. In this phase the production activities of election will be oral translation drills and communicative activities (e.g. general conversations, simulations, more complex picture tasks) under time constraints. The tasks will not limit themselves to topic X or Y; rather, they will tap on various areas of human experience at once.

It must be stressed that the four phases above may stretch over a period of several months.

3. Concluding remarks

A lot of L2 teaching nowadays concerns itself with the passing of grammar and declarative knowledge of the target language. Such knowledge stays in our students’ brains as declarative because way too often teachers are obsessed with vertical progression at all costs. This attitude, though, short-circuits and straight-jackets learning preventing the learners from truly automatizing the grammar structures and vocabulary we aim to teach them.

L2 students’ failure at acquiring what we teach them and eventually their disaffection with the learning process is often due to the inadequate amount of horizontal progression we allow for in our classrooms. Automatization, ACROSS ALL FOUR SKILLS, the ability to apply the core L2 items in the performance of tasks rapidly, fluidly and accurately should take priority in the classroom over activities which build intellectual knowledge (e.g. lengthy grammar explanations and gap-fills), concern themselves with producing artefacts (e.g. iMovies) or simply entertain (e.g. games and quizzes).

Grammar teaching is currently taught in many classrooms through teacher –led explanations followed by gap-fills. This does not lead to automatization and fluency. Grammar structures ought to be taught in the context of interaction which mimicks real life, first through communicative (highly structured) drills then through activities which increasingly allow the students more creativity and freedom in terms of output choice.

Vocabulary ought to be recycled through as many linguistic contexts as possible, shying away from the almost behaviouristic tendency one observes in many language classrooms to teach and practise the target words in isolation or almost exclusively in the same unambitiously narrow range of phrases (a tendency encouraged by current ML textbooks and many popular specialised websites, e.g. the tragically unambitious Linguascope).

In conclusion, effective ML teaching, as viewed by Skill theory, concerns itself with

- the micro-skills needed by the students to carry out the complex tasks teachers often require their students to perform. In many contexts, e.g. listening instructions,such micro-skills (e.g. decoding skills) are grossly neglected, often leading to failure and learner disaffection;

- providing the students with opportunities to automatize everything they are taught before the class move on to another set of grammar rules, vocabulary or learning strategies;

- building a wide-ranging processing history so that many neural connections are built between a new target item and as many ‘old’ items as possible through real-time language exposure/use;

- fluency, i.e. the ability to perform each target L2 item as rapidly and accurately as possible;

- skill-building rather than knowledge-building. Knowledge building is only the starting point of acquisition; that is why error correction that merely informs of the error and cryptically states the rule is considered as having very limited impact on learning.

For those interested in finding out more, please check out this online article by Jensen (2007) [click on the rectangular download button]

References and suggested bibliography

Anderson, J.R. (1987). Skill acquisition Compilation of weak-method solutions. Psychological Revie. 94(2) 192-210

Anderson. J.R. et al. (1994). Acquisition of procedural skills from examples. Journal of experimental psychology, 20, 1322 -1340.

DeKeyser, R.M. (1998). Beyond focus on form: Cognitive perspectives on learning and practicing a second language grammar . In C. Doughty and J. Williams. (EDs). Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition. (pp42-63) New York: Cambridge university Press

Jensen, E. (2007) Introduction to brain-compatible learning, 2nd edn. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Corwin Press

Johnson, K. (1996). Language Teaching and Skill learning. Oxford: Blackwell.

Schneider, W. & Shiffrin. R. (1997) Controlled and automatic information processing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.