Please note: this post was written in collaboration with Steve Smith of ‘The Language Teacher toolkit’ and Dylan Vinales of Garden International School

1.Introduction – Beyond testing and quizzing

A recurrent theme in my blogs is the belief that Modern Language listening instruction, as it is currently carried out in many L2 classrooms, is more about testing than modelling. Students are usually asked to listen to a text uttered at near-native or native speed and answer a set of questions on it which typically involve picking out a few details here and there or deciding whether some statements made about that text are true or false. In other words, quizzes through and through, which often elicit a lot of guesswork from the students who are not always adequately prepared for them and equipped at best with basic inference strategies.

Add to this the fact that typically the aural input found in textbooks and other published resources does not contain the repetitions, redundancies and cues that not only facilitate understanding, but also make language more noticeable and memorable.

To make things worse, students are usually asked to listen to each listening extract two or three times maximum and the pre-listening task preparation and post-task recycling are usually minimal. Once the marking is over and done with, the class move on and the listening track just listened to is usually not revisited again. As it is obvious, not much learning occurs, as such practice does not allow for many opportunities for students to notice and analyse new language items and patterns.

This model is seriously at odds with the way humans learn languages in the early stages of first language acquisition, where input from caregivers and the family entourage is usually fairly highly patterned, repetitive and cue-rich (especially in terms of visual input) and the same language is recycled over and over again in very similar contexts with frequent positive and negative feedback which confirms or negates the children’s inferences.

Such an approach to listening instruction also clashes with the way in which much second language learning occurs in naturalistic/immersive environments, where L2 learners usually develop their listening skills through extensive oral interaction with native speakers or other L2 experts who repeat, paraphrase, explain and use plenty of cues to facilitate the comprehension of their input. In real life, humans are active listeners who use their eyes as much as their ears to comprehend their interlocutor’s input often cueing them to any breakdown in communication and negotiating meaning with them when that happens.

- 2. The aims of this post

In this post I reiterate and expand on a concept I put across in my article ‘Listening Instruction Part 1′. The notion, that is, that at lower levels of proficiency listening instruction should concern itself more with listening-as-modelling (henceforth LAM) than with listening for testing comprehension.

But WHY is it crucial to implement LAM ?

First and foremost, as it is obvious, to prepare our student for aural comprehension, the most important skill in real-life communication – around 45 % of total real-life communication involving the listening modality whilst only 15 % occurs through reading and only 10% through writing. If our learners acquire the L2 target grammar and vocabulary almost exclusively through the written medium – as it often happens – they will struggle when processing it aurally, a common phenomenon in the typical UK classroom. On the other hand, frequent exposure to LAM will enhance their ability to code new input thereby lessening the processing cognitive load and – as an added benefit – facilitating the noticing of any grammatical and syntactic features in aural input.

Secondly, masses of LAM will impact students pronunciation and decoding skills, which in turns may enhance their oral and reading skills. Effective listening comprehension requires mastery of bottom-up processing skills as much as it does top-down. LAM develops learner bottom-up processing skills by constantly modelling L2 vocabulary, functions, grammar and syntax through the listening medium.

Thirdly, by aiming at modelling rather than quizzing, LAM allows for the explicit instruction of grammar and syntax through the listening medium – which is impossible during listening comprehension tasks as the students are focusing on answering questions.

Fourthly, the fact that LAM recycles the same core items time and again and is highly patterned makes the input more accessible and memorable.

3. Eight features of effective LAM practice

To be most effective, LAM activities – as I envisage them- should:

- address all levels of language processing, from the phonological features of words to the understanding of larger discourse structures (long sentences and paragraphs) both in terms of meaning and how they function;

- include highly patterned (e.g. lots of repetition) comprehensible input uttered at a speech rate which is accessible to the target learners;

- start with highly structured and highly scaffolded activities which become gradually less structured and more demanding;

- Start with smaller units of discourse and gradually build up to larger ones;

- involve a variety of tightly-sequenced tasks which recycle the same language items and patterns;

- prepare the students for any subsequent listening comprehension tasks;

- avail itself of visual aids and other cues (e.g. typographic devices to translation) which facilitate understanding of the input;

- explicitly promote the noticing of new L2 items

In the below, I will show how this can be done through low effort and high impact activities which I have been using for a long time and have significantly impacted my students’ proficiency. Most of the activities below are not rocket science and you may be implementing some of them already in your lessons – although probably not as often as I would advocate. Interestingly, some of them are regarded as ‘legacy methods’ and are consequently somewhat frowned upon, despite the fact that recent research seems to indicate they can indeed positively impact proficiency.

- The mindshift advocated: from quizzing on listening to teaching through listening

Although the activities, their design, their sequencing and implementation are important factors to consider in the implementation of listening instruction, the key issue is the mindshift that it is advocated here: from quizzing on listening to teaching through listening.

This shift requires teachers to adopt a different attitude, deploy a different range of strategies and set different expectations. It doesn’t do away with listening comprehensions, as I do believe they play an important role, too, in fostering the development of crucial inference strategies.

The difference is that in the approach I advocate, listening comprehensions are staged at the end of an instructional sequence; after much listening-as-modelling and other activities recycling and drumming in the target input have occurred. At a stage, that is, in which the students are actually ready to carry out the listening-comprehension task(s), because they will have processed by then most of the language they need to know to successfully complete it/them several times over through listening-as-modelling activities and other modalities (e.g. reading and speaking tasks).

Hence listening-as-modelling serves two functions: on the one hand it models new language; on the other it prepares the learner for listening comprehension tasks, which could be viewed in this sense as plenaries designed to assess whether uptake of the target vocabulary or structures has occurred.

5. Some LAM activities

5.1. Caveat

The following is a list of the modelling-as-listening activities that are easier to prepare and implement and which, in my professional experience have high surrender value. As it is obvious, for effective modelling to occur, teachers will carry out a sequence of three or four of these activities per lesson, ensuring that each activity recycles the same target L2 items over and over again. Moreover, as already stated above, modelling should start through highly scaffolded activities targeting lower-order processing skills and gradually move on to higher-order ones.

A recurrent feature, which I believe to be the greatest strength of LAM of the kind advocated here, is that every single one of the activities below calls for the application of two or more skills of the same time. For instance, Micro-listening enhancers, partial dictations and sentence builders involve reading and writing as well as listening and dictations can also be used to enhance transformational writing skills and even promote cognitive comparison and metalinguistic enhancement.

Three types of LAM activities are absent from the list below as they are already common currency in the typical language classroom and it is thus taken for granted that most teachers use them. Firstly, the common practice of uttering a set of vocabulary items and asking the class to repeat them one or more times; secondly, playing a recording of a dialog /role-play and asking the students to re-read it; thirdly, teacher fronted talk in the target language. It should be noted, however, that the effectiveness of the first two of the above practices is usually undermined by the fact that any word processed aurally does not linger in Working Memory for longer than two seconds and is overwritten by any new incoming information. Hence, if there is no abundant recycling after the initial aural exposure, retention of the phonological level of the input is usually quite poor .

As for fronted-teacher talk in the target language, it is a listening-as-modelling practice that has great potential for learning when the input is carefully and craftily constructed to explicitly model language through lots of repetition, highly patterned discourse, reference to audio-visuals and/or realia and techniques which focus students on specific language items and allow Noticing to occur. Sadly, though, the teacher fronted-talk I have witnessed over 25 years of teacher training and observations in British classrooms is rarely planned and constructed this way and often novice to intermediate students only get the gist of what the instructor says without learning much from it.

5.2 Sample LAM activities

5.2.1 Micro-listening enhancers (MLEs)

Since I have talked about MLEs extensively in previous blogs, it will suffice to say here that they consists of phonological-awareness-raising activities which aim at developing decoding and coding skills, i.e. the ability to turn letters and combination to sounds and to match sounds to letters and combination of letters. As mounting research evidence shows, these skills are crucial to effective listening and even reading skills (Macaro, 2007).

I use these activities on a daily basis prior to staging more challenging listening or speaking activities to focus on sound that students find more problematic, as way to prep them. Examples of these activities can be found at this link. Here are four types of MLEs that I use a lot:

- Spot the foreign sound (students listen to the teacher as s/he utters L2 words and identify sounds that do not exist in their language, whilst inductively working out letter-to-sound equivalence)

- Spot the silent letter (example: Furniture, Chair, Wardrobe, Fridge)

- Minimal pairs (e.g. Chair / Cheer ; Sink / Think; Hair/heir )

- Fill in the missing letters

It is important to note that the words/phrases used in the MLE activities ought to be part of the target vocabulary one aims to teach in the lesson-at-hand.

5.2.2 Sentence builders / Writing mats

Sentence builders or writing mats are an excellent way to model writing through listening whilst at the same time teaching vocabulary. The teacher makes up sentences in the target language using the words in each column/box reading them aloud a few times at accessible speed and students write them out in their native language on mini-whiteboards or iPads (the way I use them within a full lesson sequence is outlined in more detail here). I usually embed the translation of new/challenging in the sentence builder/writing mats to facilitate comprehension.

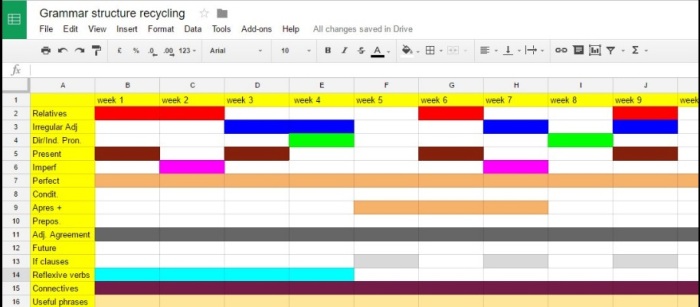

As a follow-up, the sentences made in the process can be recycled in any of the activities below. This is one of the sequences I use: teacher-led sentence builder > narrow listening > student-led sentence builder (group-work) > structured oral interaction (e.g. communicative drills eliciting vocabulary/phrases modelled in the sentence builder activity) > reading aloud (if time) > listening comprehension (to assess uptake of target items) . Obviously, each activity will recycle the input found in the sentence builder + a few unfamiliar items thrown here and there to spice up the language and elicit inference strategies.

5.2.3 Dictations and partial dictations – beyond forging good spelling habits…

Although they are often dubbed as ‘legacy methods’ , there is mounting research evidence that dictations and partial dictations can positively impact listening comprehension ability (e.g. Marzban et al, 2013; Kuo, 2010). Dictations can be used to enhance other important aspects of L2 proficiency beside word spelling and coding/decoding skills. For instance, I use them quite frequently to model correct grammar and even transformations writing strategies. These are but a few uses one can make of dictations:

- To model vocabulary usage. Partial dictations are an excellent means to focus students’ attention on specific vocabulary items and collocations whilst at the same time modelling their pronunciation and how they relate syntactically to other words. When the missing words are new, I usually provide the L1 translation in brackets, next to the gap. I find partial dictations particularly valuable when teaching L2 items which are notoriously less salient (e.g. prepositions, articles, word endings) and go often unnoticed;

- To teach grammar. In a cognitive-comparison activity, the teacher displays a number of sentences in the L1 on the board/screen and dictates to the students the translation of those sentences in the L2 to raise their awareness of important morphological and/or syntactic differences between the two languages in conveying the same meaning. The students write out the sentences, are asked to spot the differences and work out the relevant L2 grammar rules inductively.

- To provide feedback on learner errors. After identifying a number of common errors in the student oral and/or written output in the handling of a set of L2 items, the teacher displays on the board incorrect L2 sentences in which those errors have been embedded. S/he will then dictate the correct L2 version of those sentences and ask the students to compare differences and work out the rules that were flouted in the erroneous output.

- To model transformational writing skills. As already discussed in a previous blog (here)sentence recombining tasks can be powerful tools to develop transformational writing skills. Dictations can be used to model sentence-recombining strategies. Take the sentences:

My mother is friendly, funny and affectionate. / She can be stingy at times. / She often tells me off for being lazy

Through dictation students can be shown various ways in which they can be recombined (e.g. My mother is friendly, funny and affectionate but can be stingy at times and often tells me off for being lazy or although my mum can be stingy at times and often tells me off for being lazy, she is friendly, funny and affectionate, etc.). After several aural examples, more written examples may be provided and subsequently the students can have a go at sentence recombining themselves

5.2.4 Reading aloud

Short sessions of reading aloud passages recycling the lesson’s target vocabulary followed by equally short comprehension tasks (e.g. list five points made in the passage you have just read) or even oral translation are minimal-preparation tasks that have been shown to significantly impact students’ oral proficiency (Seo, 2014). I usually get students to read aloud to each other in dyads or triads and it works quite well. However, more able students enjoy it more than less able ones, especially when dealing with longer texts. I tend to shy away from carrying out reading aloud with long texts.

5.2.5 Jigsaw listening

This is a classic which the students enjoy and another minimal preparation activity. Mounting research evidence points to its effectivennes in enhancing listening comprehension skills (e.g. Fajar Satria Pambudi et al, 2013). All you have to do is get hold of the transcript of an audio-track, jumble the lines up and put the resulting text on the screen for student to put it back together in its original form as they listen to the recording. I usually carry it out before staging a listening comprehension task (using its transcript for the jigsaw activity), especially with weaker groups, highlighting items that I want to draw the students’ attention to.

5.2.6 Narrow listening

I have dealt with narrow listening and narrow reading extensively in previous blogs. They consist of a set of short passages on the same topic which contain highly patterned input and recycle the same vocabulary to death, with very few variations. The high recycling and the recurring patterns facilitate understanding and recall. I usually get the students to carry out very short comprehension tasks on them which increase in difficulty as they progress through them. See an example here. I use narrow listening a lot and it has definitely enhanced my students’ listening skills. I usually follow it up with narrow reading activities recycling the same language.

5.2.7 Nursery rhymes, poems and songs

Songs are possibly the best LAM activities because of their potential for motivation. However, to have the highest surrender value they should recycle the lesson’s target items – which is not always easy. If you have a talented musician amongst your ML colleagues you can get them to alter the lyrics of popular songs to include the target vocabulary or structures. I do have one such colleague and draw on his talent on a weekly basis.

Songs, nursery rhymes and poems can be exploited for many purposes at a range of levels (see my post here). As a LAM activity, I usually exploit them by (a) gapping the lyrics; (b) doing a jigsaw listening task; (c) inserting random extraneous words that they need to identify and circle as they listen and (d) doing a transcription task of a whole section of it (e.g. the refrain or a stanza).

- Highly patterned story-telling with visual cues.

Story-telling can be very powerful but requires lots of preparation when we are dealing with lower proficiency group, so I tend to use it mostly with strong intermediate or with upper intermediate groups. The story should be interesting and the input should be highly patterned and accessible and recycle the lesson’s target items; moreover it is advisable to prep the students through a lot of vocabulary-building activities prior to the activity to lessen the cognitive load during the story-telling. I usually tell the story in short instalments. After each instalment I show the transcript of what I have just read on the screen, ask a few comprehension or what-comes-next questions and move on to the next bit.

Concluding remarks

In this post I have made a case for a mind-shift in listening instruction from quizzing on aural input to teaching and learning through aural input. I have described a range of minimum-preparation / high-impact Listening-as-modelling (LAM) activities that use aural input to model pronunciation, decoding skills, sentence building and to enhance the acquisition of lexical and grammar items through cognitive comparison, noticing and abundant recycling.

The frequent use of LAM activities in my lessons has greatly enhanced my students’ learning, the most tangible outcome being substantial gains in their pronunciation, decoding skills, oral fluency and general listening comprehension. Hence, I strongly recommend ML teachers incorporate LAM activities in their every lesson, mindful of the following recommendations I made in paragraph 3, above:

- include highly patterned (e.g. lots of repetition) comprehensible input uttered at a speech rate which is accessible to the target learners;

- start with highly structured and highly scaffolded activities which become gradually less structured and demanding;

- start with smaller units of discourse and gradually build up to larger ones;

- use a variety of tightly-sequenced tasks which recycle the same language items and patterns;

- each LAM activity should prepare the students for any subsequent listening comprehension tasks;

- make use of visual aids and other cues (e.g. typographic devices to translation) which facilitate understanding of the input;

- explicitly promote the noticing of any new L2 items in the aural input.

Listening comprehension tasks should be staged after the linguistic material they contain has been processed aurally through a range of LAM activities so as to ensure that our students are no more engaged in mere guesswork, but that they actually come to the task prepared. This shift from guesswork to ‘know work’ may not only enhance their chances to understand but also their sense of efficacy and self-esteem as listeners.

For more on our views on language teaching and learning do get hold of our book “The Language Teacher Toolkit” available here

You must be logged in to post a comment.