Introduction

As I prepare a series of workshops for MFL teachers in Australia, I’ve taken the opportunity to delve deeply into some of the most recent and relevant research on vocabulary acquisition—specifically focusing on studies published over the last ten years. This review is not just academic: it’s been prompted by an increasing number of schools, teacher associations, and training providers asking me to share evidence-informed strategies for vocabulary instruction. The fact that so many are requesting input in this area speaks volumes about the growing awareness that vocabulary is not just one part of the curriculum—it is the foundation upon which comprehension, fluency, and spontaneous speech are built.

The findings presented below are not abstract or theoretical. They speak directly to the reality of MFL classrooms: mixed-ability learners, time constraints, and pressure to deliver measurable progress. What unites these ten insights is their practical value. They can be embedded in daily practice, whether we’re planning a Key Stage 3 scheme of work or reviewing how vocabulary is recycled and assessed at GCSE.

Most of the findings reinforce practices many experienced MFL teachers already use—structured input, chunking, sentence-level modelling. Others offer opportunities to tweak, challenge, or strengthen what we do. All are grounded in robust research and point toward the same goal: helping learners retain and use words more effectively, more confidently, and more independently.

1. Repetition Through Speaking and Listening Strengthens Memory

(Carter, 2017; Chien & Chen, 2020)

When vocabulary is encountered and reused through speaking and listening tasks, it is retained more effectively (50% better!) than vocabulary encountered only in written form. This is partly due to the way the brain encodes sound through the phonological loop—a system that favours oral and aural input for long-term memory formation.

In MFL classrooms, this has major implications. Learning vocabulary through listening activities (e.g. through circling, multiple-choice quizzes, ‘Listen and Draw, ‘Gapped translation’, ‘Faulty translation’) and speaking ones (paired speaking tasks, drills, speaking frames, and oral question-answer routines) don’t just build fluency—they deepen retention. Hearing and saying phrases like “je vais aller” repeatedly in context (e.g. during information-gap tasks or speed dating activities) anchors them in memory far more effectively than copying them into a book.

2. Timely Feedback on Word Use Makes a Difference

(Schmitt & McCarthy, 2019; Carrol, 2017)

Timely, specific feedback on vocabulary use—whether oral or written—can lead to a 20% increase in future accuracy. This is because feedback delivered close to the point of error helps learners notice and adjust their internal language models before misconceptions become entrenched.

In MFL lessons, this might involve live marking during extended writing, highlighting commonly misused words after a speaking assessment, or using peer correction with model answers. It also reinforces the importance of activities that make learner thinking visible—such as mini whiteboards or sentence-building tasks—so that misconceptions can be addressed immediately.

3. Digital Tools Can Help—If Used Consistently

(Godwin-Jones, 2017; Stockwell, 2020)

Digital platforms that use spaced repetition have been shown to improve vocabulary retention by up to 40%, especially when they are used regularly and linked to classroom learning. These tools support memory by prompting recall at increasingly spaced intervals, just as learners are about to forget.

For MFL departments, this suggests value in embedding digital vocabulary tools into weekly routines—not just recommending them for homework, but explicitly training pupils how to use them well. Creating class sets aligned with schemes of work or homework review quizzes on digital platforms can turn receptive vocabulary exposure into active recall practice. Make sure, however, that the exposure to the target vocabulary is as multimodal as possible (i.e. encompassing all four skills) as happens, for instance, on http://www.language-gym.com.

4. Motivation Significantly Boosts Vocabulary Retention

(Macaro et al., 2020; Dörnyei, 2019)

Motivated learners retain up to 50% more vocabulary than their less engaged peers. This is because motivation increases attention, effort, and willingness to review and reuse vocabulary over time. Crucially, it also increases the likelihood that learners will use words spontaneously.

In the MFL classroom, motivation can be nurtured through small but meaningful strategies: building in student choice, celebrating visible progress (e.g. class word count trackers) and linking vocabulary tasks to topics learners care about. For example, letting learners describe their own weekend plans rather than invented characters makes vocabulary personal, which in turn makes it stick. Engaging interactive vocabulary games involving mini whiteboard use and fun retrieval practice activities such as ‘Faster’, the ‘4,3,2 technique’ and digital games (e.g. the Language Gym’s ‘Boxing game’ and the ‘Vocab Trainer’) will help too, of course.

5. Receptive Vocabulary Develops 1.5 Times Faster than Productive Vocabulary

(Gyllstad, 2020; Nation, 2020)

It is entirely natural for learners to recognise and understand vocabulary long before they are able to use it themselves. Receptive vocabulary develops 1.5 times faster than productive vocabulary because it places less demand on syntax, spelling, pronunciation, and retrieval.

This finding validates the use of input-focused tasks—narrow reading, listening with targeted vocabulary, and teacher-led modelling—before expecting learners to write or speak. It also supports the use of structured scaffolds (sentence builders, gapped texts, writing frames) that help bridge the gap from passive recognition to active production over time.

6. Learners Need to Encounter a Word 15–20 Times Before It Sticks

(Webb, 2016; Elgort, 2018)

A few encounters with a new word are not enough. Learners typically need between 15 and 20 meaningful, spaced exposures before a word moves into long-term memory. These encounters must be varied and multimodal—reading, hearing, saying, and writing the word in different contexts.

This underscores the importance of recycling vocabulary not just across lessons, but across units and terms. A word like “parce que” should appear not just in Year 7 but in every subsequent year. Activities such as sentence transformation, low-stakes quizzes, retrieval grids, and structured translation can ensure repeated exposure over time.

7. Vocabulary in Context Is Remembered Better

(Hulstijn, 2018; Coxhead, 2018)

Words are learnt more effectively (30% better retention!) when they are taught in meaningful context rather than in isolation. Context helps learners understand usage, grammar, and connotation. It also provides semantic and syntactic cues that aid retention.

In practice, this means presenting vocabulary within phrases and full sentences—not just as English–French pairs. Model sentences, listening texts, and reading activities that repeat key phrases provide both form and function. Sentence builders, in particular, allow learners to see how vocabulary fits grammatically within familiar structures.

8. Collocations and Chunks Reduce Errors and Build Fluency

(Laufer & Goldstein, 2020; Schmitt, 2019)

Learners who are taught vocabulary in the form of collocations (e.g. “avoir faim”, “faire une promenade”) or multi-word chunks (e.g. “il y a”, “je suis en train de”) make fewer errors (30% accuracy improvement!) and produce more fluent speech. These combinations are stored and retrieved as whole units, reducing cognitive load during speaking and writing.

For MFL teachers, this supports focusing less on isolated nouns and more on useful chunks that include verbs, prepositions, and time expressions. Teaching “je vais + infinitive” or “normalement je + present tense” as building blocks helps learners speak more fluently and write more accurately.

9. Explicit Instruction Improves Accuracy by Around 25%

(Gass, 2019; Macaro, 2021)

When vocabulary is taught explicitly—rather than left to be inferred through exposure—learners show a 25% improvement in accuracy. This includes clear explanations of meaning, form, grammar, pronunciation, and common collocations.

In the MFL classroom, this reinforces the value of modelling pronunciation, pointing out tricky gender rules, and explicitly teaching the difference between similar words. Rather than relying solely on discovery learning, it encourages deliberate instruction through worked examples and teacher-led practice.

10. Vocabulary Size Drives Comprehension

(Meara, 2017; Nation, 2020)

Learners need to know approximately 2,000 to 3,000 word families to understand 85% of general texts. This is a threshold for independent comprehension. Below it, learners are likely to become discouraged due to too many unknowns.

For MFL teachers, this highlights the importance of focusing on high-frequency vocabulary across all key stages. It’s tempting to focus on topic-specific words, but the bulk of our time should be spent on the most common verbs, connectors, and adjectives. Structured vocabulary progression models and high-frequency word trackers can help ensure systematic exposure and development.

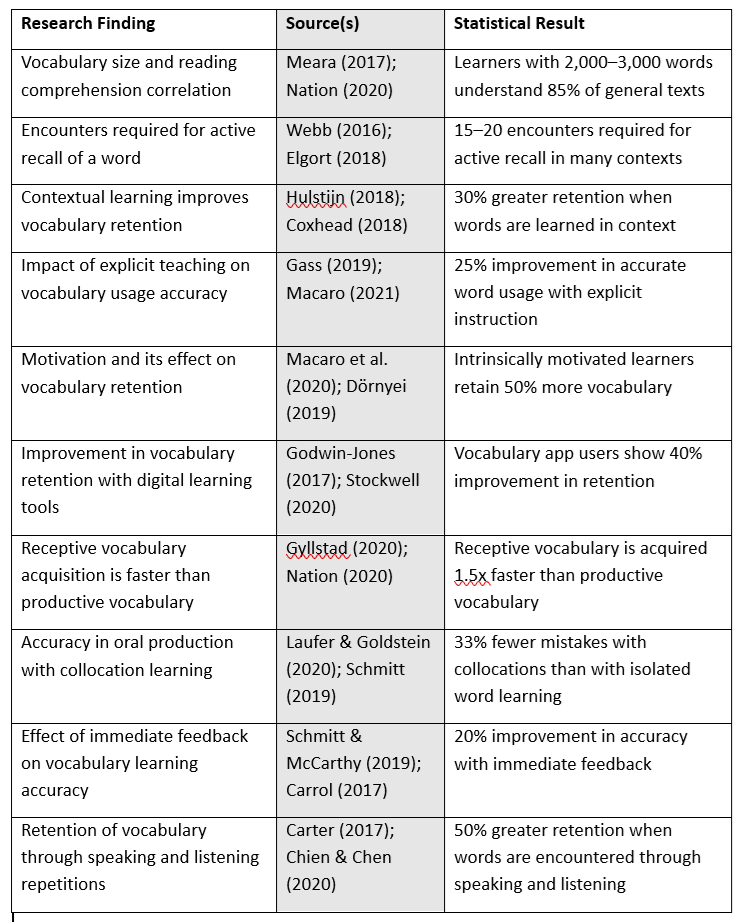

11. Summary of the findings

Conclusions

As I prepare to share these findings with colleagues during my workshops in Australia, I’m reminded that vocabulary learning is rarely immediate. It is a slow-building process that depends on repetition, motivation, context, and structure. Teaching vocabulary effectively means helping learners meet the same word multiple times, in meaningful ways, and with the support they need to process and retrieve it.

These ten findings, taken together, point us toward a vocabulary curriculum that is cumulative, focused, and deeply rooted in how memory works. They validate many of the techniques MFL teachers already use—retrieval practice, chunk teaching, sentence-level work—and offer encouragement that these approaches are not only intuitive, but research-backed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.