Introduction

As I gear up for my upcoming speaking tour—six cities across Australia over the next two weeks—I’ve been reflecting on the foundational studies that have shaped the way we teach and think about instructed second language acquisition. In doing so, I’ve returned once more, this time with particular focus – aural strategies instruction, to a study that has been quietly transformative in how we approach listening: Graham and Macaro (2008).

Why this study? Because listening comprehension, though undeniably central to language learning, is often the least explicitly taught of the four core skills. For beginner and lower-intermediate learners, the challenges are considerable: decoding fast speech, parsing unfamiliar vocabulary, coping with reduced forms, and making meaning with limited phonological awareness. These are compounded by low self-confidence and scarce exposure to naturalistic input.

In their 2008 paper, Graham and Macaro proposed a practical and well-structured model of listening strategy instruction tailored to the secondary school classroom. Their research showed that explicitly teaching students how to listen—rather than simply testing whether they had understood—led not only to improved comprehension outcomes but also to increased confidence and greater strategic awareness. The study’s findings have since been echoed in subsequent replications by other researchers, underscoring its potential.

But as any teacher will ask: is this model realistic in the daily grind of an overloaded classroom? Can its benefits be maintained when scaled down or adapted? And what does it actually look like in practice?

In this article, I explore these questions by offering a thorough summary of the study, unpacking its methodology and findings, and evaluating the feasibility of adapting its core principles into mainstream language teaching contexts.

Summary of Graham & Macaro (2008)

Graham and Macaro’s study investigated the effects of explicit strategy instruction on the listening skills of Year 9 French learners in the UK. Based on Vandergrift’s metacognitive framework, the researchers developed a 12-week programme in which learners were taught to plan, monitor, problem-solve, and evaluate their listening. Students were guided through a strategy cycle comprising pre-listening prediction, first listening for gist, post-listening strategy reflection, second listening with focused goals, and an evaluative phase.

Pre-Test Findings

Before the intervention, both the experimental and control groups completed a diagnostic listening comprehension assessment. The findings revealed that learners struggled particularly with understanding spoken French when confronted with longer texts, fast speech, or tasks requiring inference. The majority of students approached listening as a test of word recognition and expressed frustration when they could not understand every word. Metacognitive awareness, such as the ability to reflect on strategies or evaluate performance, was low across both groups, and few students reported using prediction, selective attention, or inference strategies. These pre-test results provided a strong rationale for introducing explicit strategy training.

Methodology

The study employed a quasi-experimental design with two matched groups: one receiving strategy-based instruction (experimental group) and one following traditional listening pedagogy (control group). Both groups consisted of Year 9 learners with comparable attainment levels.

The experimental group received 12 weeks of strategy instruction embedded in their regular listening lessons. Each session followed a structured cycle:

- Pre-listening: Students activated prior knowledge and predicted content based on titles and visuals.

- First listening: Students listened for gist without writing answers.

- Reflection: Learners discussed what they understood and the strategies they used.

- Second listening: Focused listening tasks aimed at identifying detail or specific language features.

- Post-listening: Learners evaluated their comprehension and reflected on the effectiveness of the strategies used.

The control group received the same listening texts and tasks but without explicit strategy teaching or metacognitive reflection. Assessments included pre- and post-tests of listening comprehension, a metacognitive awareness questionnaire, and follow-up interviews.

Materials Used

The materials for the intervention were carefully designed to be age-appropriate, linguistically accessible, and pedagogically structured. Audio recordings consisted of scripted and semi-authentic dialogues between native French speakers, selected to include a range of topics relevant to the learners’ syllabus, such as school life, leisure activities, and personal descriptions. Each audio track was accompanied by visual prompts (e.g., pictures, headlines, or comprehension grids) to aid prediction and focus attention.

Listening tasks were designed to assess both gist and detail comprehension and included true/false statements, multiple-choice items, and sequencing tasks. Additionally, learners were given printed worksheets that prompted pre-listening predictions and post-listening evaluations. These materials also embedded strategy prompts such as “What do you already know about this topic?” and “What helped you understand the second time?”—thereby reinforcing strategic habits.

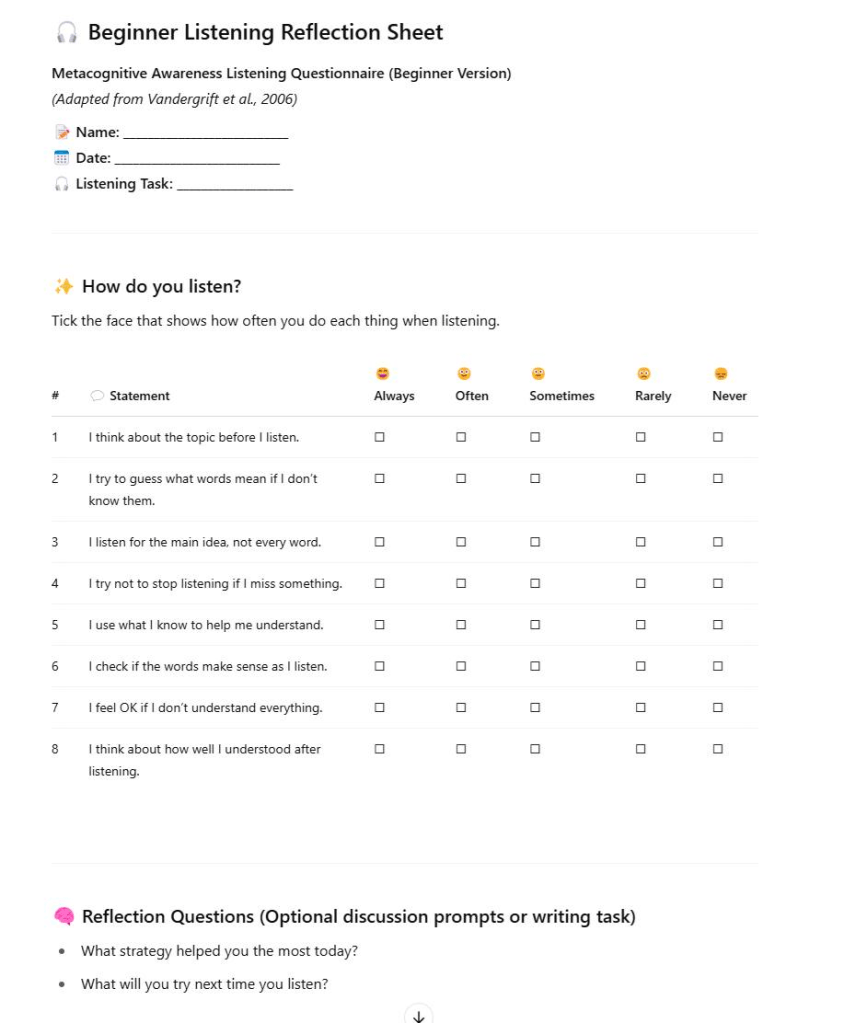

Figure 1 – Listening reflection sheet (listening strategy checklist

Target Strategies Modelled

Throughout the intervention, teachers explicitly modelled and scaffolded the following strategies:

- Prediction: Using context and visual prompts to anticipate content before listening.

- Selective Attention: Focusing on key words and ignoring unimportant details.

- Inference: Making educated guesses about unfamiliar language using known vocabulary and tone.

- Monitoring: Checking for understanding and recognising when something doesn’t make sense.

- Problem-solving: Using a combination of strategies to recover lost meaning or continue listening despite gaps.

- Evaluation: Reflecting on how well a strategy worked and adjusting approach accordingly.

Each strategy was not only introduced and explained but also consistently revisited across lessons. Teachers modelled strategies using think-aloud techniques and then encouraged learners to articulate their own strategic thinking during reflection phases.

Results

The results showed measurable differences between the two groups. Students in the experimental group showed significantly greater improvement on post-listening comprehension tests than those in the control group. These students demonstrated gains in both gist and detail comprehension, as recorded through test scores and self-reports. They were also more likely to report applying strategies such as prediction, inferencing, and monitoring during listening tasks.

The metacognitive awareness questionnaire revealed measurable gains in the experimental group in areas such as planning before listening, evaluating after listening, and remaining focused despite difficulties. In contrast, the control group showed minimal change. Qualitative data from student interviews reinforced these findings: learners in the strategy group reported feeling better equipped to cope with difficult passages and were more willing to persevere when faced with difficult listening passages. Some students expressed a sense of increased satisfaction and motivation, though such statements should be interpreted cautiously given the self-reported nature of the data.

Feasibility in Real-Classroom Settings

Despite its strengths, replicating this model on a daily basis in the typical classroom is not straightforward. Unlike the tightly controlled and researcher-supported context of the original study, real classrooms often struggle with behavioural disruptions, student disengagement, time constraints, and teacher workload.

Teachers in mainstream settings typically teach multiple year groups, plan lessons across key stages, and are accountable for high-stakes exam results. Embedding multi-phase listening cycles and structured metacognitive reflection into every lesson would require a level of consistency and time that most timetables do not allow. Furthermore, students may lack the metacognitive maturity to engage meaningfully with strategy talk, particularly in schools where language learning is not strongly valued.

It is also important to consider researcher bias. Graham and Macaro were highly motivated to make their intervention work: the time and effort invested in design, delivery, and analysis needed to produce observable results to justify publication. This level of intensity and motivation is rarely transferable to busy school settings. While the intervention was undoubtedly effective, the conditions of its delivery were unusually favourable.

Effort vs Outcome: A Cost-Benefit Evaluation

When evaluating the cost-benefit balance of this intervention, the picture is mixed. On the one hand, the learning gains were statistically significant and pedagogically meaningful. On the other, the intervention was labour-intensive, and its full implementation is unlikely to be sustainable at scale. A more pragmatic approach is to identify core components of the strategy cycle that can be maintained regularly, while spacing out or simplifying the more demanding elements.

Scalable Listening Strategy Implementation Matrix

| Component | Effort Required | Impact on Learning | Feasibility in Busy Classroom | Recommended Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-listening prediction routine | Low | Moderate | High | Every lesson (5 mins) |

| Multiple listening cycles (gist/detail) | Medium | High | Medium | 1–2x per week |

| Post-listening metacognitive discussion | High | High | Low | Occasional (after assessments) |

| Strategy checklist use (see figure 1 above) | Medium | Moderate | High | Weekly self-check |

| Teacher modelling of strategy use | Medium | High | Medium | Weekly modelling |

| Student reflective logs | High | Moderate | Low | End of unit |

Conclusion

Graham and Macaro’s 2008 study remains a cornerstone of strategy-based listening instruction, highlighting the value of teaching learners how to think about and manage their listening processes. Their 12-week intervention provided learners with tools that improved both performance and confidence, and encouraged greater listening autonomy. However, its full implementation is pedagogically ambitious and structurally difficult in many secondary schools. A strategic compromise is both necessary and desirable: teachers can adopt a reduced set of high-impact, low-effort routines that nurture listening autonomy without overwhelming their schedule. With careful planning and judicious adaptation, the core principles of metacognitive listening training can still yield meaningful gains—even under typical classroom constraints. The key is not to replicate the study in its entirety, but to extract and embed what works, sustainably.

A very important lesson to be learnt from this study, which confirms what I have observed from my own implementation of a metacognitive strategy-training programme as part of my PhD, is that teaching strategies is a very challenging, time-consuming and effortful process which must be sustained overtime in order for it to pay substantive dividends. Hence, if we want listening strategies to be taught effectively, we need to design a bespoke programme based on the needs of our students which must be delivered sistematically over a period of 3 months or even longer (my hunch is more like six months!).

References

Graham, S., & Macaro, E. (2008). Strategy instruction in listening for lower-intermediate learners of French. Language Learning, 58(4), 747–783.

Vandergrift, L. (1997). The strategies of second language (French) listeners: A descriptive study. Foreign Language Annals, 30(3), 387–409.

Vandergrift, L., Goh, C. C. M., Mareschal, C. J., & Tafaghodtari, M. H. (2006). The metacognitive awareness listening questionnaire: Development and validation. Language Learning, 56(3), 431–462.

Goh, C. C. M. (2000). A cognitive perspective on language learners’ listening comprehension problems. System, 28(1), 55–75.

Cross, J. (2011). Metacognitive instruction and second language listening: Theory, practice and research implications. TESOL Quarterly, 45(2), 269–279.

You must be logged in to post a comment.