Introduction: Echoes That Teach

Imagine a classroom where learners speak not to produce, but to echo. They’re not asked to create original sentences, but to shadow a model voice—real time, word for word, tone for tone, breath for breath. To the untrained eye, it might look like mindless mimicry. But under the hood, shadowing is an advanced, cognitively rich technique, lauded for its potential to accelerate language acquisition, especially fluency and listening.

Long used in interpreter training and increasingly recommended in applied linguistics literature, shadowing is slowly making its way into communicative classroom settings. But for it to be effective—particularly with novice or intermediate learners—it must be carefully scaffolded, ideally following scripted listening activities (Conti & Smith, 2019) and explicit phonics instruction.

This post explores what shadowing is, how it works, why it works, what research says about it, how to avoid its pitfalls, and most importantly, how to implement it successfully in classrooms following the EPI model.

What Is Shadowing?

Shadowing is the technique of listening to a piece of spoken language and immediately repeating it aloud, trying to match the speaker’s intonation, pronunciation, stress, and rhythm. Unlike delayed imitation or choral repetition, shadowing is simultaneous, usually performed within milliseconds of the original input.

It was first formalised by Tamai (1992) in Japan and later refined by Kadota (2007, 2012) as a tool for training interpreters. The learner listens and speaks at the same time, forcing their phonological loop to operate at full capacity while building motor-auditory fluency.

Why Does Shadowing Work?

Shadowing is effective because it activates multiple learning mechanisms at once. Let’s break down the key benefits:

- It Improves Auditory Discrimination and Working Memory

According to Baddeley’s (2003) model of working memory, the phonological loop is responsible for storing and processing sounds. Shadowing keeps this loop constantly active, reinforcing sound recognition and mental rehearsal. Kadota (2012) found that shadowing boosts phonological encoding, leading to better short-term retention of language chunks. - It Develops Accurate Prosody and Pronunciation

By synchronising with the speaker’s voice in real time, learners refine their intonation, pitch contours, and rhythm. Studies by Foote & McDonough (2017) and Mori (2011) show significant gains in pronunciation accuracy and prosodic fluency in ESL learners using shadowing with mobile tools. - It Proceduralises Grammar and Chunks

Shadowing promotes implicit learning by encouraging learners to internalise grammatical structures and lexical chunks without conscious analysis. It facilitates proceduralisation—the transformation of declarative knowledge into fluent, automatic output (DeKeyser, 2007; Segalowitz, 2010). - It Sharpens Listening Skills

Because it requires fine-grained attention to input, shadowing enhances decoding of connected speech, reductions, elisions, and weak forms, making learners more adept at parsing naturalistic input (Tamai, 1992; Hamada, 2016). - It Builds Cognitive Load Tolerance

The simultaneous nature of shadowing trains learners to process input and output concurrently—developing mental agility and fluency under pressure (Kadota, 2012). This is especially valuable for interpreters and advanced communicators.

How Much Is Enough?

While there’s no magic number, research offers useful guidelines:

- Kadota (2007) recommends 3–5 hours per week for measurable gains in fluency.

- Tamai (1992) observed strong improvements with 15–20 minutes daily across several weeks.

- Hamada (2016) found that lower-intermediate learners benefited significantly from short sessions (10–15 minutes, 3–4x per week) over 6 weeks.

As with most language input, regularity and quality matter more than quantity.

Foundations First: Scripted Listening and Phonics

For shadowing to yield optimal results, it should not be introduced in a vacuum—especially not with novice learners. It must follow foundational work that:

- Makes input fully comprehensible (Krashen, 1982);

- Familiarises learners with key structures and lexis;

- Helps them decode sounds explicitly.

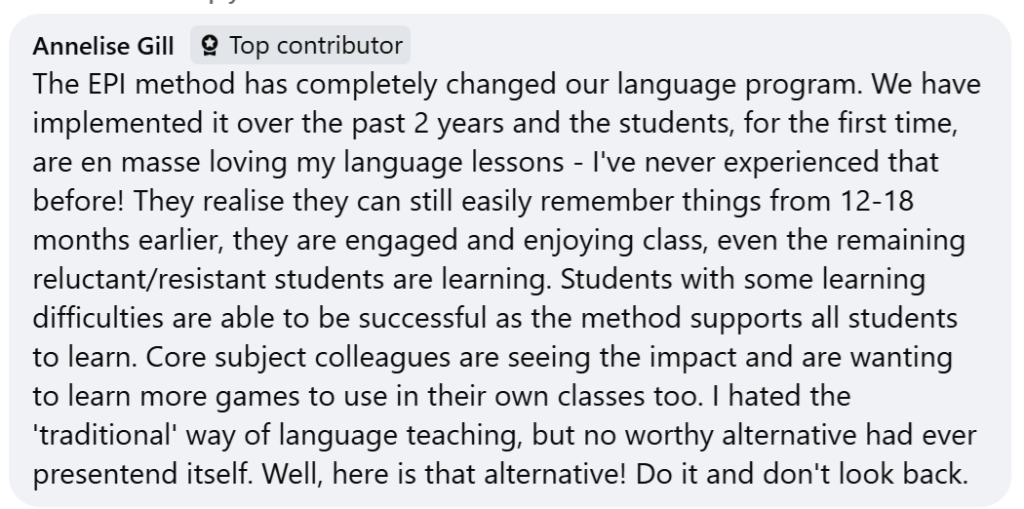

This is where Extensive Processing Instruction (EPI) comes in. EPI advocates for Scripted Listening (Conti & Smith, 2019)—intensive listening activities based on rich, recycled input with built-in scaffolds (e.g., narrow listening, aural match-ups, listening pyramids). These prime the learner’s brain with high-frequency structures and help them notice collocations and patterns.

Before or alongside shadowing, it’s also vital to carry out explicit phonics work, especially for English learners grappling with inconsistent sound-letter correspondences. Addressing common mispronunciations reduces the risk of fossilising errors during shadowing.

Pitfalls of Shadowing (and How to Avoid Them)

| Pitfall | Risk | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Mindless parroting | Learners repeat without understanding | Combine shadowing with comprehension tasks (e.g. summarising, back translation) |

| Cognitive overload | Particularly for beginners | Use graded materials, slow speed, transcript support |

| Fossilisation of errors | Incorrect forms get automatised | Do phonics work beforehand; use native audio; record and review output |

| Demotivation | Learners may find it stressful or boring | Use engaging content and gamify (e.g. shadowing speed challenges) |

Classroom Implementation Tips

- Start with “Scripted Shadowing”

Learners shadow while reading the transcript. This builds phonological confidence. - Move to Audio-Only

Once comfortable, learners shadow without transcript, chunk by chunk. - Use High-Frequency Chunks

Focus on sentence builders and recycled structures already taught (Conti, 2021). - Incorporate Output Tasks

Follow shadowing with retrieval practice: e.g., write a summary, answer comprehension questions, rephrase key chunks. - Record and Compare

Learners record their shadowing and compare it to the model—great for noticing gaps in pronunciation or rhythm. - Keep Sessions Short and Focused

10–15 minutes of intensive shadowing is better than 40 minutes of fatigued mimicry.

How you can gamify Shadowing

Here are a few tried and tested Shadowing games that can be easily incorporated in your lessons.

Conclusion: Beyond Echoes

Shadowing may look like imitation, but it’s far more than echoing sounds—it’s a full-body rehearsal of fluency. When built upon a foundation of scripted listening, phonics, and lexical patterning, it can turbocharge learners’ listening comprehension, pronunciation, and spontaneous production.

For teachers working within an EPI framework, shadowing is not just an add-on. It’s the bridge between structured input and proceduralised output. Used judiciously.

References

Baddeley, A. (2003). Working Memory and Language. Psychology Press.

Conti, G., & Smith, S. (2019). Breaking the Sound Barrier. The Language Gym.

DeKeyser, R. (2007). Practice in a Second Language: Perspectives from Applied Linguistics and Cognitive Psychology. CUP.

Foote, J. A., & McDonough, K. (2017). Using shadowing with mobile technology to improve ESL pronunciation. Journal of Second Language Pronunciation, 3(1), 34–56.

Hamada, Y. (2016). Shadowing: Who benefits and how? Language Teaching Research, 20(1), 35–52.

Kadota, S. (2007). Shadowing as a Training Method for Improving EFL Learners’ Listening and Speaking Skills. Tokyo: Taishukan.

Kadota, S. (2012). Shadowing: Let’s Speak English Like an Interpreter! Tokyo: Cosmopier.

Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Pergamon.

Mori, Y. (2011). The roles of phonological decoding and semantic access in L2 word recognition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 33(1), 1–30.

Segalowitz, N. (2010). Cognitive Bases of Second Language Fluency. Routledge.

Tamai, K. (1992). Shadouingu no Koka ni Tsuite no Kenkyuu [A Study on the Effects of Shadowing]. Tokyo: Kuroshio.

You must be logged in to post a comment.