Introduction

In the 80s and 90s, metacognition – one’s awareness and regulation of one’s own thinking and learning processes – was a big deal in educational circles. L2 researchers like O’Malley and Chamot, Wenden, Cohen and, in England, Professors Macaro (my PhD supervisor) and Graham (my PhD internal examiner), advocated vehemently for the implementation of training in metacognitive strategies as a means to improve learning outcomes.

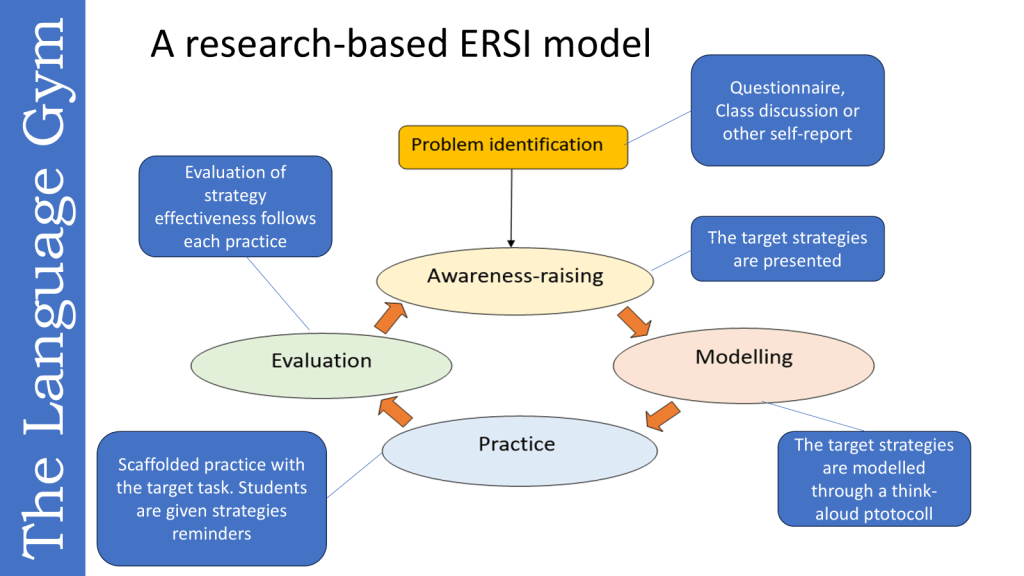

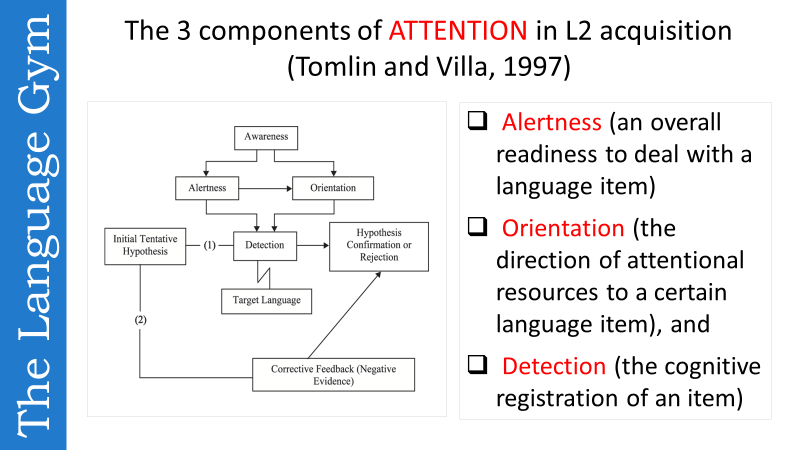

These advocates postulated, based on evidence from a handful of promising studies, that metacognition could be effectively taught following a principled framework (Explicit Strategy Training) which unfolded pretty much like the model in the picture below (ERSI = Explicit Reading Strategies Instruction), significantly enhancing L2 students performance across all four language skills.

Figure 1 – Explicit Strategy Training model

As often happens in our field, the interest fizzled out pretty soon, as language educators quickly realised that the time and effort they had to put in in order for metacognitive training (henceforth MT) to yield some substantive benefits was more than they could afford. There were other issues too, which I will explore below, to do with developmental readiness, teacher expertise and motivation, which deterred many language educators from buying into MT.

I experienced first-hand how time consuming, effortful and complex implementing an MT program is, during my PhD in Self-Monitoring strategies as applied to L2 essay writing. Mind you, the results were excellent: the training managed to significantly reduce a wide range of very stubborn errors in my students’ writing. However, the time and effort I invested in the process was something that I could have never been able to put in, had I been a teacher on a full timetable.

40 years on since its golden age, metacognition and MT are trending again in educational circles. Many schools are now implementing metacognition enhancement programs in the hope to increase learner planning, monitoring and self-evaluation skills. However, at least from what I have gleaned from my school visits, conversations with colleagues and other anecdotal data, many of these programs exhibit a number of flaws which seriously undermine their efficacy. Before delving into them, let me remind the reader of what metacognition and metacognitive strategies are about.

Metacognition and metacognitive strategies – what are they?

Having written about metacognition before, I will very briefly remind the reader of what metacognition entails.

Metacognition is the awareness and regulation of one’s own thinking and learning processes. It involves three key components:

(1) Metacognitive Knowledge—understanding how one learns best;

(2) Metacognitive Regulation—planning, monitoring, evaluating and adjusting learning strategies; and

(3) Metacognitive Experience—reflecting on past learning to improve future performance.

In language learning, metacognition helps learners set goals, choose effective strategies, and evaluate progress. It fosters independence, problem-solving, and long-term retention. Effective metacognitive strategy training enables learners to become more self-aware and adaptable, improving comprehension, speaking, and writing skills. Ultimately, metacognition transforms learners into active, strategic thinkers who optimize their own learning.

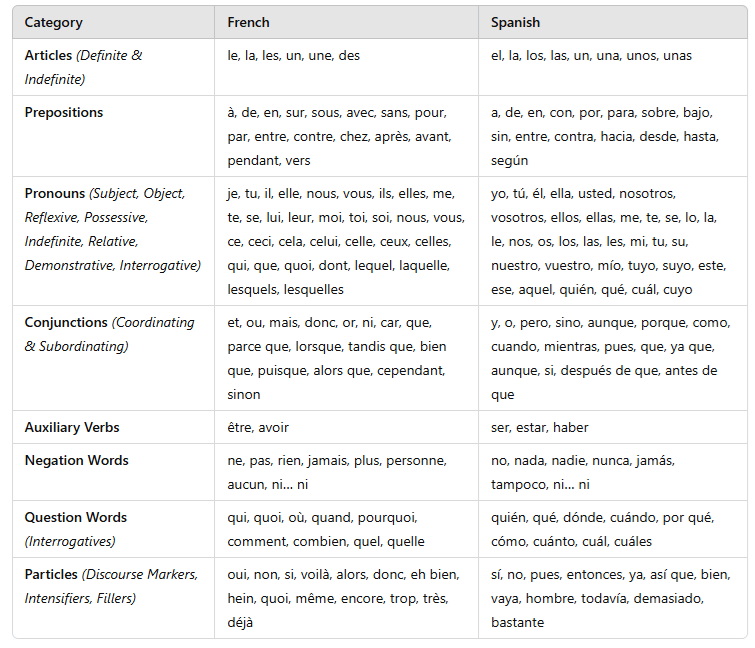

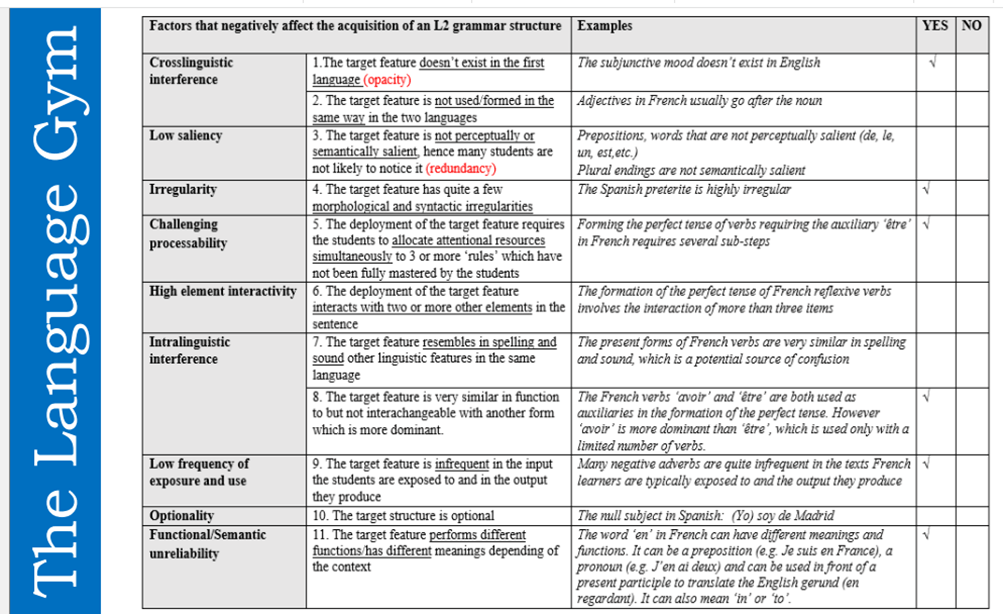

Metacognitive strategies include actions, mental operations and techniques that L2 learners undertake in order to improve their performance by planning, monitoring, self-evaluating and setting goals, Tables 1 and two below categorize metacognitive strategies into those that help with planning & monitoring and those that support self-regulation & reflection, making them easier to implement systematically.

Common shortcomings of metacognitive training programs

1️ Insufficient or Inconsistent Training Duration

Many programs do not provide enough time for learners to fully develop and internalize metacognitive strategies. Effective strategy use requires regular and long-term practice and reinforcement lasting 3 to 6 months or even longer, yet some programs last only a few weeks. This is the most common reason as to why MT programs fail according to the literature.

Example Issue:

🔹 A 4-week metacognitive training program may not show strong results because learners haven’t had enough exposure to develop automatic strategy use.

Solution:

✅ Longer programs with progressive scaffolding (e.g., training over an entire semester or year).

✅ Periodic strategy reinforcement instead of one-time instruction.

2. Lack of Explicit Training

Why It Matters

Some teachers assume that learners will naturally pick up metacognitive strategies just by being exposed to them. Implicit instruction (modeling, indirect feedback) can play an important role but on its own is often not enough—students need explicit training on how and when to use these strategies.

Example Issue:

🔹 A study where learners are simply given reading comprehension tasks but are not explicitly taught how to plan, monitor, and evaluate their reading may fail to show significant improvements.

Solution:

✅ Explicit strategy instruction with step-by-step guidance (e.g., teaching learners to pause, summarize, and predict while reading).

✅ Use of think-aloud protocols where instructors demonstrate metacognitive strategies.

3. Lack of Learner Awareness & Readiness

Why It Matters

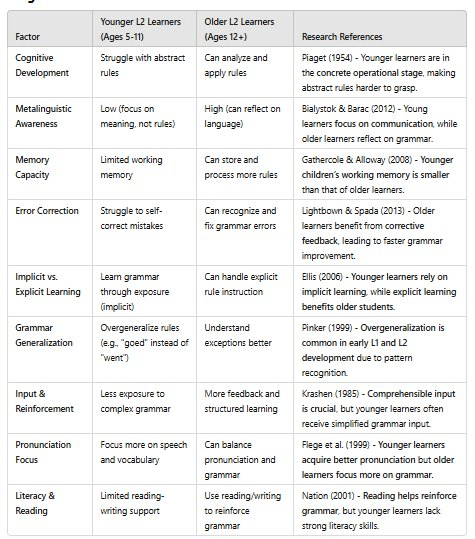

Not all learners instinctively use metacognitive strategies. Beginners or low-proficiency learners may lack the cognitive capacity to focus on both language processing and strategy application at the same time.

Example Issue:

🔹 A program implementing high-level reflection strategies with beginner learners may find little impact because they struggle with basic comprehension, making strategy use overwhelming.

Solution:

✅ Gradual introduction of simple strategies first, then progression to more complex ones.

✅ Differentiated instruction based on learner proficiency.

4. Misalignment Between Metacognitive Strategies and Task Demands

Why It Matters

Some strategies may not be suitable for the specific language task the students are being training to perform. If the strategy does not align with the nature of the task, learners may misuse or underuse it.

Example Issue:

🔹 Testing metacognitive listening strategies (predicting, summarizing) on a phoneme discrimination task may not see much improvement because phoneme recognition relies more on cognitive than metacognitive skills.

Solution:

✅ Ensure the right strategies are taught for the right tasks (e.g., metacognitive strategies are most useful for reading, writing, and listening comprehension).

✅ Train students when to use which strategy effectively.

5. Limited Learner Motivation or Engagement

Why It Matters

Some students do not see the immediate value of metacognitive strategies and fail to engage with them actively. If students are not motivated, they are unlikely to consistently apply the strategies outside of training sessions.

Example Issue:

🔹 A study assumes that students will automatically use metacognitive strategies in their self-study time, but without motivation, many learners simply do not apply them.

Solution:

✅ Increase strategy relevance by linking them to real-world benefits (e.g., improving exam performance, fluency, or confidence).

✅ Use gamification and self-reflection exercises to keep learners engaged.

6. Failure to Account for Individual Differences

Why It Matters

Learners differ in cognitive styles, motivation, and prior strategy knowledge. Some learners naturally use metacognitive strategies, while others struggle even after training.

Example Issue:

🔹 A study may average the results across all learners without considering that some learners benefited while others did not.

Solution:

✅ Conduct pre-tests to determine baseline strategy use before training.

✅ Use personalized strategy training rather than a one-size-fits-all approach.

✅ Use multiple assessment methods (e.g., think-aloud protocols, task-based assessments, real-time monitoring).

✅ Measure language proficiency gains alongside self-reports.

7. Teacher Expertise & Implementation Issues

Why It Matters

Some teachers may not be adequately trained in metacognitive instruction, leading to ineffective delivery.

Example Issue:

🔹 A program on listening strategy training fails to show strong results because teachers do not provide clear modeling or feedback.

Solution:

✅ Ensure teacher training in explicit strategy instruction.

✅ Use standardized instructional methods across all participants.

8. Short-Term vs. Long-Term Impact Measurement

Why It Matters

Some program measure effects immediately after training, missing potential long-term benefits. Metacognitive strategies often require time to internalize before showing clear benefits.

Example Issue:

🔹 A program finds no significant impact after 4 weeks, but if measured after 6 months, the results might be different.

Solution:

✅ Conduct longitudinal follow-ups to check delayed improvements.

✅ Use delayed post-tests to assess strategy retention.

Conclusion: Why do many metacognitive training programs fail?

Many MT programs fail to show strong effects because of:

- Too short training duration – Not enough time for mastery.

- The students may not be cognitively ready – MT does require the application of higher order skills

- The students may simply not be interested – they are there to learn a language and may not see the long-term benefits or what you are trying to achieve

- Lack of explicit strategy instruction – Students don’t know how to use the strategies effectively.

- Poor alignment of strategies with tasks – Wrong strategies for the wrong skills.

- The teachers simply do not have the know-how to teach metacognitive skills

Any Language educator wanting to teach metacognition should bear the above issues in mind before embarking on an MT program. Following a trend can be a very perilous endeavour, especially in a field like L2 acquisition, in which the research evidence that MT programs actually work is very fragmented and inconclusive.

If you want to know more about Metacognition and metacognitive training, you can attend any of my workshops organised by http://www.networkforlearning.org.uk

You must be logged in to post a comment.