Introduction

Why do some students seem to acquire languages with ease, while others struggle despite a lot of effort? In every classroom, there are individuals who appear to possess an intuitive grasp of grammar, pick up new vocabulary and grammatical patterns instantly, replicate native-like pronunciation with minimal practice and can produce long and complex sentences accurately when their classmates can barely slap down two words together. These learners are often described as “gifted,” but what exactly does that mean in the context of language learning? This article aims to unpack the factors that contribute to exceptional aptitude in language acquisition. Drawing on decades of research in second language acquisition (SLA), cognitive science, and neurobiology, I present and explain ten traits that distinguish gifted language learners from their peers.

In my curriculum design workshops, I always begin by emphasising that effective language programming hinges on a deep understanding of both the learners and the learning context. Identifying the key cognitive and affective traits that underpin successful acquisition allows us to build smarter curricula—ones that stretch the gifted without leaving others behind. When we know what makes a learner gifted, we can build programmes that amplify these strengths, compensate for weaker areas in others, and provide meaningful differentiation. This has implications for everything from instructional materials to task design, formative assessment, and classroom grouping. Ultimately, a clear grasp of these attributes equips educators to create learning environments that challenge the most able while remaining accessible to all.

Ten key factors that make a learner gifted at languages

Table 1: Ranked Table of Key Factors

| Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Working Memory Capacity | Verbal short-term memory and attentional control |

| 2. Phonemic Coding Ability | Precision in sound perception and reproduction |

| 3. Motivation and Goal Orientation | Intrinsic drive and long-term learning focus |

| 4. Metalinguistic Awareness | Ability to reflect on and manipulate language consciously |

| 5. Pattern Recognition and Rule Abstraction | Sensitivity to regularities in input |

| 6. Implicit Learning Ability | Capacity to absorb rules without awareness |

| 7. Resilience to Ambiguity and Failure | Tolerance for confusion and errors |

| 8. Cognitive Processing Speed | Quick access to lexical and syntactic knowledge |

| 9. Cross-linguistic Transfer and Awareness | Use of L1/L2 to support L3 |

| 10. Attentional Control and Noticing | Ability to notice salient input features |

1. Working Memory Capacity

Gifted language learners tend to have an exceptional ability to temporarily store and manipulate verbal information. This working memory advantage helps them hold chunks of new input (like verb endings or sentence frames) in mind long enough to decode patterns, apply rules, or formulate output. Studies by Miyake & Friedman (1998) and Baddeley (2003) confirm that verbal working memory strongly predicts grammatical sensitivity and syntactic accuracy in both instructed and naturalistic learners.

2. Phonemic Coding Ability

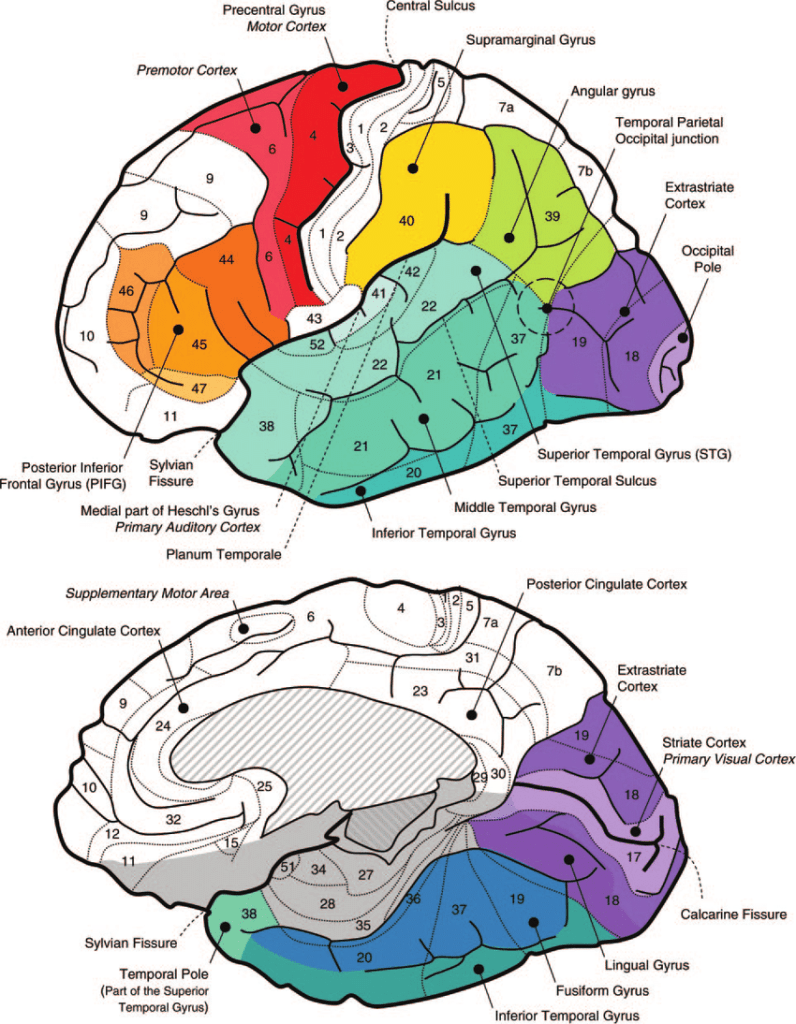

Another major hallmark is the ability to distinguish, store, and reproduce unfamiliar phonemes with high accuracy. This trait, rooted in auditory discrimination and fine motor control, supports rapid development of accurate pronunciation and listening comprehension. Research by Golestani et al. (2002) shows that this ability is even reflected in brain structure, with gifted learners displaying more robust auditory cortex morphology.

3. Motivation and Goal Orientation

Even the most cognitively endowed learner will flounder without motivation. What sets gifted learners apart is not just high motivation, but the right kind: intrinsic, task-focused, and often integrative (i.e., driven by a desire to connect with the target culture). As Gardner & Lambert (1972) and Dörnyei (2009) show, this kind of motivational resilience sustains long-term effort, encourages persistence through failure, and fuels deeper processing of input.

4. Metalinguistic Awareness

Gifted learners often demonstrate an early and advanced ability to analyse and discuss language explicitly. This metalinguistic awareness allows them to compare structures across languages, self-correct efficiently, and make conscious hypotheses about grammar and usage. Jessner (2006) and Bialystok (1988) argue that this meta-awareness supports both explicit instruction and autonomous learning.

5. Pattern Recognition and Rule Abstraction

One of the most underrated traits of gifted linguists is their knack for detecting patterns. They quickly pick up on regularities in verb endings, word order, or syntax, and generalise rules based on exposure. According to Carroll (1981) and DeKeyser (2000), this form of grammatical inference is central to building a coherent interlanguage system without relying solely on instruction.

6. Implicit Learning Ability

In addition to being good at noticing patterns consciously, gifted learners are often able to internalise rules implicitly, through mere exposure. This capacity — linked to procedural memory — enables them to learn complex grammatical behaviours (like gender agreement or tense alternation) without needing formal instruction. Reber (1989) and DeKeyser et al. (2010) highlight that this subconscious system works in tandem with explicit systems in high-aptitude learners.

7. Resilience to Ambiguity and Failure

Gifted learners are unusually comfortable with confusion. Rather than being paralysed by ambiguity or error, they view it as a natural part of the learning process. This tolerance, documented by Ehrman (1996) and Dewaele & Li (2013), reduces anxiety, increases willingness to take communicative risks, and encourages exploration of difficult input.

8. Cognitive Processing Speed

Quick access to stored lexical and grammatical knowledge is another advantage. High processing speed allows learners to parse complex input, monitor their output, and adjust in real-time — critical for fluent interaction. Segalowitz (2010) and Robinson (2005) connect this trait with fluency, task success, and working memory efficiency.

9. Cross-linguistic Transfer and Awareness

Many gifted language learners are also multilingual, and they skillfully leverage their L1 or L2 to bootstrap new forms in an L3. This includes recognising cognates, comparing morphosyntactic patterns, and avoiding negative transfer. Research by Ringbom (2007) and Cenoz (2003) shows that multilingual awareness enhances language acquisition speed and depth.

10. Attentional Control and Noticing

Finally, gifted learners excel at noticing subtle but important input features — whether morphological endings, idiomatic turns of phrase, or rule violations. This attentional control is not merely about “focus” but about knowing what matters. Ellis (2006) and VanPatten (2004) demonstrate that noticing is a precursor to acquisition, and gifted learners are adept at it.

When Are These Traits Most Crucial?

While all the traits described can contribute to success at any stage, some become especially crucial during specific phases of language learning. In the early stages—typically Years 7 and 8—phonemic coding ability, working memory, and implicit learning capacity are particularly important, as they support initial decoding of input, vocabulary retention, and the formation of basic syntactic structures. In the middle years, such as Years 9 and 10, metalinguistic awareness, motivation, and pattern recognition gain prominence—enabling learners to compare languages, sustain long-term effort, and derive rules from broader input. In more advanced phases, often Years 11 and beyond, traits like attentional control, resilience to ambiguity, and cross-linguistic awareness are key for tackling complex texts, refining output, and transferring knowledge across contexts.

Why Understanding Giftedness Matters for Curriculum Design

When designing a language curriculum, it’s not enough to know what to teach — we also need to understand who we’re teaching. The ten traits that define gifted language learners don’t just help us identify those with exceptional aptitude; they offer powerful insights into how we can make our curricula more targeted, effective, and inclusive. These ten learner traits are not just theoretical abstractions—they offer practical blueprints for curriculum design. Understanding them allows us to sequence content more effectively, balance input and output, and design tasks that play to learners’ cognitive strengths while supporting their weaker areas. For example, recognising the role of working memory helps us structure language chunks and retrieval practice; knowing the importance of phonemic coding ability highlights the need for rich listening input early on. Motivational factors shape how we frame tasks and goals, while metalinguistic awareness and pattern recognition suggest the value of guided discovery and rule noticing. Traits like implicit learning, attentional control, and tolerance for ambiguity inform how we scaffold grammar and introduce complexity. Cross-linguistic awareness encourages transfer tasks, while fast processing and noticing ability shape our use of fluency-building and feedback routines. In short, these factors guide how we pitch, pace, and personalise language instruction for optimal impact.

1. Working Memory Capacity

Learners with high working memory excel when tasks require holding and manipulating multiple pieces of information. This implies curricula should begin with chunked language (e.g., sentence builders), gradually increasing complexity while integrating memory supports like scaffolds, sentence stems, and visuals for those with lower capacity.

2. Phonemic Coding Ability

Learners who can distinguish and reproduce sounds accurately benefit most from early and rich auditory exposure. A good curriculum should include regular listening practice, pronunciation drills, and phoneme discrimination activities, especially in Year 7 and 8 when learners are building their phonological map.

3. Motivation and Goal Orientation

Curricula that ignore motivation risk losing even the most cognitively able learners. Including interactive games, student-led projects, intercultural themes, and tasks with real-world communicative purpose fosters deeper investment. Units should be designed with progression and personal relevance in mind, particularly around Years 9–10.

4. Metalinguistic Awareness

Highly aware learners thrive when encouraged to reflect on rules and patterns. A curriculum should incorporate occasional grammar discovery tasks (e.g., guided inductive activities), metalinguistic comparisons across languages, and opportunities for learners to co-construct rules.

5. Pattern Recognition and Rule Abstraction

Curricula should allow learners to explore and derive rules themselves, rather than always being told what the rule is. Text enhancement, colour coding, and structured input tasks help students spot patterns and deepen their grammatical intuition.

6. Implicit Learning Ability

For those strong in implicit learning, immersion, repetition, and input flooding are crucial. The curriculum should include regular exposure to language-rich listening and reading experiences, and delay explicit rule explanation until patterns have emerged naturally.

7. Resilience to Ambiguity and Failure

To build this trait, curricula must include low-stakes risk-taking opportunities: open-ended tasks, problem-solving, peer interaction, and, in year 10 to 13, frequent exposure to unfamiliar language in context. Teachers should model tolerance of ambiguity and reward effort over perfection.

8. Cognitive Processing Speed

Fast processors excel in spontaneous tasks. The curriculum should include frequent fluency activities like speed translations, retrieval games, and automaticity-building routines to capitalise on this strength while supporting others with repetition and pacing strategies.

9. Cross-linguistic Transfer and Awareness

Students with multilingual awareness should be encouraged to draw comparisons across languages. Curriculum activities should explicitly invite transfer (e.g., cognate recognition, false friend spotting, structural contrasts), particularly useful in Years 10–11 for writing and reading.

10. Attentional Control and Noticing

Curricula should offer opportunities for noticing through input enhancement (e.g., bolding target structures), gap-fill tasks, and spot-the-error challenges. Noticing supports acquisition and reinforces both form and function in context.

Conclusion

Giftedness in language learning is not a mystical gift, but a confluence of well-documented cognitive, motivational, and experiential traits. Understanding these characteristics can help educators better support not only their most advanced students, but also raise the overall effectiveness of their teaching by embedding strategies that develop these skills in all learners. While some students arrive in our classrooms with a clear head start, with the right instruction, scaffolding, and encouragement, many of these traits can be nurtured and cultivated in every learner. Recognising the diversity of aptitude is the first step toward inclusive, responsive, and truly learner-sensitive pedagogy.

If you’re designing a language curriculum, training teachers, or mentoring learners, recognising and nurturing the ten traits above can make a profound difference. While not every student will tick every box, many can be trained to develop these capacities with the right support.

In my next post I will delve in greater detail into the implications of the above factors for curriculum design and classroom teaching.

References (selected by salience)

- Baddeley, A. (2003). Working memory and language: An overview. Journal of Communication Disorders, 36(3), 189–208.

- Cenoz, J. (2003). The additive effect of bilingualism on third language acquisition: A review. International Journal of Bilingualism, 7(1), 71–87.

- DeKeyser, R. (2000). The robustness of critical period effects in second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 22(4), 499–533.

- effects in second language acquisition. Applied Psycholinguistics, 31(3), 413–438.

- Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The psychology of second language acquisition. Oxford University Press.

- Ehrman, M. E. (1996). Understanding second language learning difficulties. Sage.

- Ellis, N. C. (2006). Selective attention and transfer in SLA: Contingency, cue competition, salience. Applied Linguistics, 27(2), 164–194.

- Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second-language learning. Newbury House.

- Golestani, N., Molko, N., Dehaene, S., LeBihan, D., & Pallier, C. (2007). Brain structure predicts success in learning foreign speech sounds. Cerebral Cortex, 17(3), 575–582.

- Miyake, A., & Friedman, N. P. (1998). Individual differences in second language proficiency: Working memory as language aptitude. In A. F. Healy & L. E. Bourne Jr. (Eds.), Foreign language learning: Psycholinguistic studies on training and retention.

- Ringbom, H. (2007). Cross-linguistic similarities in foreign language learning. Multilingual Matters.

- Robinson, P. (2005). Aptitude and second language acquisition. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 25, 46–73.

- Skehan, P. (2016). Language aptitude revisited: Theoretical issues. In G. Granena & D. Long (Eds.), Sensitive periods, language aptitude, and ultimate L2 attainment (pp. 29–49). John Benjamins.

You must be logged in to post a comment.