Why some words just stick—and others vanish

Let’s face it: some words are annoyingly sticky, while others are as slippery as wet soap. Any teacher who’s spent five minutes in a language classroom knows this. You’ve probably wondered: why can learners remember chien, gato, or Haus, but not espérer, crecer, or vergessen? The answer lies in research—and lots of it.

In this post, I’m going to walk you through ten factors that influence how easy (or hard) a word is to learn, drawing on the science of second language acquisition and my own years of observing students learning French, Spanish, and German. More importantly, I’ll show how to make all of this practical, with clear implications for classroom practice.

1. Frequency: Words need airtime

Words that learners encounter often are learned more easily. That’s not just teacher instinct—it’s one of the most well-established findings in second language acquisition research. Nation (2001) and Ellis (2002) both showed that repeated, meaningful exposure strengthens memory traces and increases the likelihood of recall and use. In simple terms: if a word turns up a lot, students are more likely to notice it, understand it, remember it, and eventually use it.

In languages like French, Spanish and German, the most frequently used words are often highly irregular, functionally critical, and foundational for everyday communication. Think avoir, ser, sein—these are the glue that hold the sentence together.

The role of frequency is not just about how many times a word appears, but how it appears: in varied, engaging, and multimodal contexts. Encounters across different tasks and modalities—reading, listening, speaking, and writing—reinforce learning far more effectively than isolated repetition.

Implications for the classroom: Design your curriculum around high-frequency words using corpora-informed lists and real-life language samples. Build in multiple, spaced, and varied encounters. Don’t teach a word once and move on. Use narrow reading, retrieval practice, and oral recycling strategies to keep core vocabulary alive and active. Combine receptive and productive practice to ensure frequency supports fluency, not just recognition.

2. Concreteness: You can’t picture freedom

Concrete words—things you can see, touch, taste, or hear—are more memorable than abstract ones. Paivio’s Dual Coding Theory (1991) helps explain why: concrete words are encoded both verbally and visually in the brain. Learners can form mental images of chat, mesa, or Apfel, but struggle to visualise justice, libertad, or Ehre.

Concrete words also tend to be more context-rich and emotionally engaging in classroom activities. They often lend themselves to visual support, story-building, and physical enactment, all of which increase the chances of retention. Abstract words, by contrast, are more likely to be confused or forgotten without explicit strategies to reinforce their use.

Implications for the classroom: Front-load your curriculum with highly imageable, concrete vocabulary. Use realia, flashcards, mime, and classroom objects to bring these words to life. Pair new vocabulary with vivid visual or kinaesthetic input. Delay abstract nouns and idiomatic expressions until learners have a stronger foundation in the target language and are more confident inferring meaning from context.

3. Cognates: Use them, but use them wisely

Cognates—words that sound and mean the same in two languages—are great accelerators of learning. Research by Ringbom (2007) shows they’re picked up more quickly due to positive transfer from the first language. When learners already have a mental representation of the form and meaning, all they need to do is map it onto the target language, which reduces cognitive load.

However, cognates can also backfire. False friends—words that look similar but have different meanings—can create confusion and fossilised errors. For example, actuellement in French means “currently,” not “actually,” and embarazada in Spanish means “pregnant,” not “embarrassed.” Left unchecked, these errors can persist for years and may be particularly difficult to unlearn.

Implications for the classroom: Leverage true cognates early to build learner confidence and vocabulary quickly. Use them to scaffold understanding in reading and listening texts. At the same time, explicitly highlight false cognates using visual contrasts, translation tasks, or matching games. Encourage learners to keep personal lists of false friends and review them regularly. Cognates are powerful tools—but only when handled with precision.

4. Sound and Spelling: If it sounds weird, it sticks less

Phonological and orthographic simplicity support word learnability. Ellis and Schmidt (1997) found that unfamiliar or irregular sound–spelling correspondences create additional cognitive load and delay word recognition and recall. For example, the French word oiseau (bird) is tricky for learners because it includes silent letters and unexpected letter combinations. German compounds like Staubsauger (vacuum cleaner) are long and morphologically dense, while Spanish tends to be more phonemically transparent.

When learners cannot decode a word easily, it undermines both recognition and pronunciation, making them less likely to use it in speaking or writing. Learners may avoid unfamiliar forms altogether or mispronounce them in ways that interfere with communication and fluency.

Implications for the classroom: Choose beginner vocabulary that follows regular and predictable sound–spelling patterns. Use phonics training, particularly in French and German, to reinforce decoding skills. Model pronunciation clearly and frequently. Encourage learners to build up phonological awareness gradually by comparing similar words and practising minimal pairs. When introducing tricky spellings, link them to familiar sounds or rhymes.

5. Morphology: Patterns help memory

Morphologically related words—words that share a root—are easier to remember. Nation (2013) argues that building awareness of derivational and inflectional families allows learners to store and retrieve vocabulary more efficiently. A learner who recognises that hablar, hablo, and hablamos all share a root will retain them more easily. Likewise, in German, recognising the shared root in lesen, liest, las, and gelesen can enhance comprehension and production.

Morphological transparency also helps learners make educated guesses about unfamiliar words. If they know écrire means “to write,” they are better positioned to understand écrivain (writer) or réécrire (to rewrite). This not only expands vocabulary breadth but also deepens learners’ understanding of how the language system works.

Implications for the classroom: Highlight word families through colour-coding, word maps, and suffix trees. Group vocabulary by root, not just by topic. Use matching or sorting activities that focus on form–meaning relationships. Encourage learners to track prefixes, suffixes, and root patterns in reading texts. When introducing verbs, showcase full paradigms early so learners can spot consistencies and predict new forms.

6. Context: Words don’t live in isolation

Words embedded in meaningful, engaging contexts are more memorable than words taught in lists. Nagy et al. (1985) found that inferencing meaning from context can rival direct instruction in its effects. When learners encounter manger in a short story about a picnic or spielen in a dialogue about hobbies, they don’t just memorise the word—they absorb its usage, tone, and emotional weight.

Rich context creates multiple connections: lexical, grammatical, pragmatic, and cultural. These connections act as memory hooks, making recall easier and more intuitive. Additionally, contextualised vocabulary promotes deeper processing and gives learners the “why” and “how” behind word use, not just the “what.”

Implications for the classroom: Ditch decontextualised word lists in favour of stories, dialogues, and tasks that simulate real communication. Pre-teach vocabulary through short narratives, and revisit the same words in new settings. Use content-based instruction or theme-based units that provide extended exposure. Include guided noticing tasks where learners deduce word meaning from linguistic and situational clues.

7. Emotion and personal connection

Words tied to personal relevance or emotion tend to stick. Schwanenflugel et al. (1992) found that emotional salience increases depth of processing, improving recall. Learners don’t forget words that describe their passions, frustrations, or favourite activities. When learners choose words that matter to them—whether it’s chanson, canción, or Lied—the word becomes part of their identity, not just their vocabulary.

Emotion enhances memorability through affective engagement and increased attention. It also builds autonomy and motivation, which are critical for sustained vocabulary learning. Personal connections are the bridge between memory and meaningful use.

Implications for the classroom: Integrate student choice into vocabulary learning. Provide vocabulary banks related to hobbies, interests, or identity and let students select a portion of words they want to learn. Encourage self-curated vocabulary notebooks. Use creative writing, role plays, and projects that allow learners to personalise language. Ask learners to justify or rate words based on emotional resonance or usefulness in their own lives.

8. Word type: Not all parts of speech are born equal

Some grammatical categories are easier to acquire than others. Gentner (1982) showed that nouns are more easily learned than verbs or adjectives, because they’re more concrete and less syntactically complex. Nouns tend to map directly onto tangible referents, while verbs require learners to grapple with tense, aspect, and argument structure.

Adjectives, too, can present challenges—especially in languages with agreement systems like French or German. Meanwhile, function words such as prepositions and determiners, although frequent, are abstract and difficult to define, making them harder to acquire despite their ubiquity.

Implications for the classroom: Start with a curriculum rich in high-frequency concrete nouns. Delay instruction of abstract verbs, adjectives, and function words until learners have a solid foundation in basic grammar and vocabulary. When teaching verbs and adjectives, use sentence builders and role play to support their integration into spoken and written output. Use visual organisers that show part-of-speech relationships to help learners navigate categories.

9. Semantic transparency

Words with one clear meaning are easier to learn than polysemous words (words with multiple meanings). Cross (2009) noted that ambiguous vocabulary takes longer to process and recall. Learners encountering feuille (leaf/sheet), banco (bank/bench), or Schloss (lock/castle) need to hold multiple possible meanings in mind and rely heavily on context to decode correctly.

This can lead to confusion, misinterpretation, or overgeneralisation. Beginners are especially vulnerable, as they often lack the linguistic and contextual tools to resolve ambiguity efficiently. Semantic transparency therefore plays a critical role in initial vocabulary acquisition and instructional sequencing.

Implications for the classroom: Choose semantically clear, concrete words at the early stages of learning. Avoid overloading students with polysemous or idiomatic items until they have sufficient exposure to contextual cues. When introducing ambiguous words, provide multiple examples of usage and practice inferencing with support. Use pictures, definitions, and example-rich contexts to disambiguate and reinforce accurate meaning.

10. Collocations: Words that travel in packs

Words are often easier to learn when they’re taught as part of multi-word units. Schmitt and Carter (2004) showed that collocations and formulaic sequences aid recall and fluency by reducing cognitive processing time and enhancing automaticity. When learners internalise phrases like prendre un café, tener razón, or eine Entscheidung treffen, they bypass the need to construct each element separately.

Learning words in collocation also supports pragmatic competence—knowing not just what to say, but how native speakers typically say it. It strengthens grammatical intuition and speeds up processing in both comprehension and production.

Implications for the classroom: Teach vocabulary in chunks from the very beginning. Use sentence builders, dialogues, and substitution drills to embed target collocations. Create opportunities for learners to use formulaic language in real-time tasks like discussions or role play. When presenting new words, always give examples in typical phrase structures rather than as isolated items. Focus on high-frequency, contextually useful word combinations.

Final thoughts

So what does all of this mean for classroom practice? It means that how we choose and sequence vocabulary is far from arbitrary—it should be grounded in what we know about how words stick. Some words are more learnable than others, and knowing why can give us the edge we need to make vocabulary learning more efficient, more enjoyable, and more effective.

Start by focusing on high-frequency words. These form the backbone of basic communication and will give your learners the most mileage early on. Don’t just teach them once—make them pop up again and again, in reading, listening, speaking, and writing tasks.

Use concrete, imageable words wherever possible, especially in the early stages. They’re easier to visualise, easier to link to prior knowledge, and more memorable. Support them with pictures, mime, gestures, or real objects.

Cognates are fantastic for building confidence—just be careful with false friends. Teach them explicitly and contrast them with the true ones. Learners love to spot patterns between languages, and rightly so—it helps them build their internal lexicons faster.

Phonology and spelling matter more than we think. When words sound strange or look unpredictable, they’re harder to store. Early on, prioritise words that are easy to decode and pronounce, especially in languages with tricky sound–spelling rules like French or German.

Build morphological awareness early. Group verbs and nouns by families, and highlight roots and affixes that recur across multiple words. It’s a powerful way to stretch vocabulary and deepen memory.

Don’t teach words in isolation. Create rich, meaningful contexts through stories, dialogues, and real-world tasks. Words stick when they’re emotionally and semantically grounded.

And finally, let your learners choose some of the words they learn. Vocabulary tied to hobbies, emotions, or everyday life will always win the memory battle. Language is personal—make sure vocabulary learning is too.

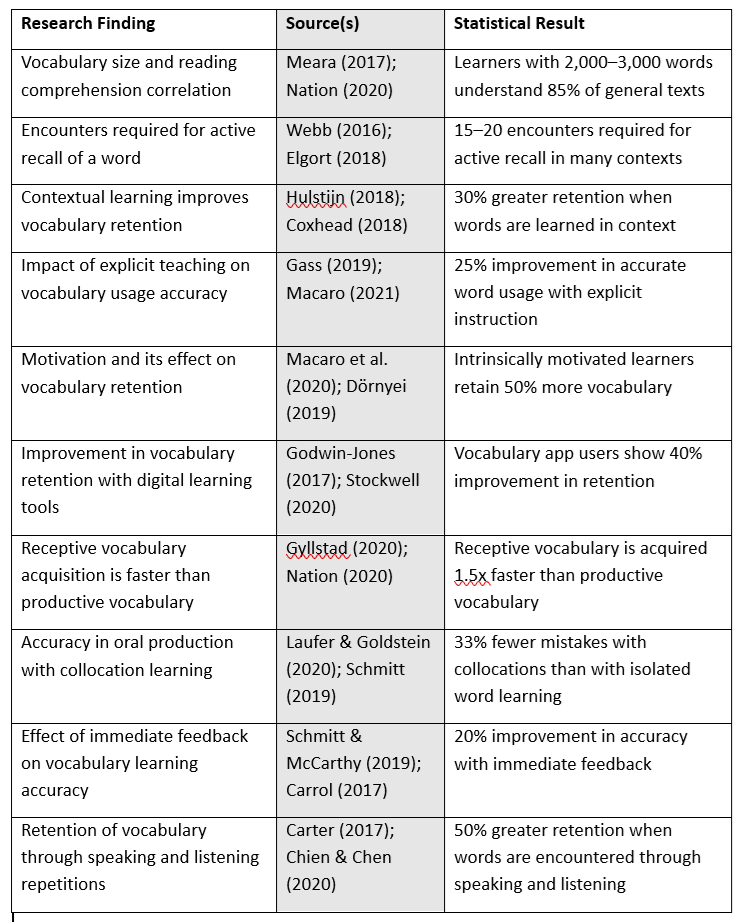

Summary Table: What Affects Word Learnability?

| Factor | Why It Matters | Examples (FR / ES / DE) | Practical Tip |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Repeated exposure boosts acquisition (Ellis, 2002; Nation, 2001) | être / ser / sein | Teach and recycle high-frequency words early and often |

| Concreteness | Concrete nouns are easier to visualise and recall (Paivio, 1991) | chat / mesa / Apfel | Use visuals, gestures, and realia |

| Cognates | Facilitate positive transfer from L1 (Ringbom, 2007) | animal / animal / Haus | Teach true cognates, warn about false friends |

| Sound/Spelling | Irregular forms are harder to decode (Ellis & Schmidt, 1997) | oiseau / coche / Staubsauger | Focus early vocab on transparent phoneme-grapheme correspondences |

| Morphology | Word families aid recall (Nation, 2013) | hablo / parler / sprechen | Group related forms and teach affixes |

| Contextual Richness | Words in context stick better (Nagy et al., 1985) | manger / jugar / lesen | Use stories, dialogues, and real-world tasks |

| Emotional Connection | Personal relevance increases salience (Schwanenflugel, 1992) | chanson / canción / Lied | Let students pick words linked to their interests |

| Word Class | Nouns are easier than verbs/adjectives (Gentner, 1982) | chien / flor / Buch | Start with nouns, scaffold verbs |

| Semantic Transparency | Single-meaning words are easier (Cross, 2009) | feuille / banco / Schloss | Delay ambiguous/polysemous words |

| Collocations | Phrases aid retrieval (Schmitt & Carter, 2004) | prendre un café / tener razón / Entscheidung treffen | Teach chunks, not just words |

If there’s one thing I’ve learned in 30 years of teaching, it’s this: how we choose and teach vocabulary matters. A lot. Some words will be forgotten no matter what, but by focusing on what the research says about learnability, we can stack the odds in our learners’ favour

Teach the high-frequency. Prioritise the concrete. Exploit the cognates (carefully). Embed in context. Teach patterns. Honour personal interest. And above all—keep things memorable, meaningful, and motivating.

Because at the end of the day, the most learnable word is the one that actually gets used.

References

- Barcroft, J. (2004). Second language vocabulary acquisition: A lexical input processing approach. Foreign Language Annals, 37(2).

- Laufer, B. (1997). The lexical threshold of second language reading comprehension: What it is and how it relates to L1 reading ability. In Vocabulary: Description, Acquisition and Pedagogy, CUP.

- Laufer, B., & Nation, P. (1999). A vocabulary-size test of controlled productive ability. Language Testing, 16(1).

- Webb, S. (2007). The effects of repetition on vocabulary knowledge. Applied Linguistics, 28(1).

- Carroll, J.B. (1992). The role of lexical transfer in vocabulary acquisition. In Arnaud & Béjoint (Eds.), Vocabulary and Applied Linguistics.

- Cross, J. (2009). Effects of polysemy on vocabulary learning. Language Awareness, 18(3).

- Ellis, N.C. (2002). Frequency effects in language processing. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 24(2).

- Ellis, N.C., & Beaton, A. (1993). Factors affecting the learnability of foreign language vocabulary. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 46(3).

- Ellis, N.C., & Schmidt, R. (1997). Morphology and second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19(2).

- Gentner, D. (1982). Why nouns are learned before verbs: Linguistic relativity versus natural partitioning. Language, 58(2).

- Nagy, W., Herman, P., & Anderson, R. (1985). Learning words from context. Reading Research Quarterly, 20(2).

- Nation, I.S.P. (2001). Learning Vocabulary in Another Language. Cambridge University Press.

- Nation, I.S.P. (2013). Learning Vocabulary in Another Language (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Paivio, A. (1991). Dual Coding Theory: Retrospect and Current Status. Canadian Journal of Psychology.

- Ringbom, H. (2007). Cross-Linguistic Similarity in Foreign Language Learning. Multilingual Matters.

- Schmitt, N. (2008). Instructed second language vocabulary learning. Language Teaching Research, 12(3).

- Schmitt, N., & Carter, R. (2004). Formulaic sequences in action. ELT Journal, 58(4).

- Schwanenflugel, P. et al. (1992). Emotional content and word processing. Cognition & Emotion, 6(6).

You must be logged in to post a comment.