A cognitive account of errors in L2-writing rooted in skill acquisition and production theory

1. Introduction

2. Key concepts in Cognitive psychology

Before engaging in my discussion of L2-acquisition and L2-writing, I shall introduce the reader to the following concepts, central to any Cognitive theory of human learning and information processing:

1. Short-term and Long-Term Memory

2. Metalinguistic Knowledge and Executive Control

3. The representation of knowledge in memory

4. Proceduralisation or Automatisation

2.1 Short-Term Memory and Long-Term Memory

In Information Processing Theory, memory is conceived as a large and permanent collection of nodes, which become complexly and increasingly inter-associated through learning (Shiffrin and Schneider, 1977). Most models of memory identify a transient memory called ‘Short-Term Memory’ which can temporarily encode information and a permanent memory or Long-Term Memory (LTM). As Baddeley (1993) suggested, it is useful to think of Short-Term Memory as a Working Short-Term Memory (WSTM) consisting of the set of nodes which are activated in memory as we are processing information. In most Cognitive frameworks, WSTM is conceived as the provision of a work space for decision making, thinking and control processes and learning is but the transfer of patterns of activation from WSTM to LTM in such a way that new associations are formed between information structures or nodes not previously associated. WSTM has two key features:

(1) fragility of storage (the slightest distraction can cause the brain to lose the data being processed);

(2) limited channel capacity (it can only process a very limited amount of information for a very limited amount of time).

LTM, on the other hand, has unlimited capacity and can hold information over long periods of time. Information in LTM is normally in an inactive state. However, when we retrieve data from LTM the information associated with such data becomes activated and can be regarded as part of WSTM.

In the retrieval process, activation spreads through LTM from active nodes of the network to other parts of memory through an associative chain: when one concept is activated other related concepts become active. Thus, the amount of active information resulting can be much greater than the one currently held in WSTM. Since source nodes have only a fixed capacity for emitting activation (Anderson, 1980), and this capacity is divided amongst all the paths emanating from a given node, the more paths that exist, the less activation will be transmitted to any one path and the slower will be the rate of activation (fan effect). Thus, additional information about a concept interferes with memory for a particular piece of information thereby slowing the speed with which that fact can be retrieved. In the extreme case in which the to-be-retrieved information is too weak to be activated (owing, for instance, to minimal exposure to that information) in the presence of interference from other associations, the result will be failure to recall (Anderson, 2000).

2.2 Metalinguistic knowledge and executive control (processing efficiency)

This distinction originated from Bialystock (1982) and its validity has been supported by a number of studies (eg Hulstijin and Hulstijin, 1984). Knowledge is the way the language system is represented in LTM; Control refers to the regulation of the processing of that knowledge in WSTM during performance. The following is an example of how this distinction applies to the context of my study: many of my intermediate students usually know the rules governing the use of the Subjunctive Mood in Italian, however, they often fail to apply them correctly in Real Operating Conditions, that is when they are required to process language in real time under communicative pressure (e.g. writing an essay under severe time constraints; giving a class presentation; etc.). The reason for this phenomenon may be that WSTM’s attentional capacity being limited, its executive-control systems may not cope efficiently with the attentional demands required by a task if we are performing in operating conditions where worry, self-concern and task-irrelevant cognitive activities make use of some of the available limited capacity (Eysenck and Keane, 1995). These factors may cause retrieval problems in terms of reduced speed of recall/recognition or accuracy. Thus, as Bialystock (1982) and Johnson (1996) assert, L2-proficiency involves degree of control as well as a degree of knowledge.

2.3 The representation of knowledge in memory

Declarative Knowledge is knowledge about facts and things, while Procedural Knowledge is knowledge about how to perform different cognitive activities. This dichotomy implies that there are two ‘paths’ for the production of behaviour: a procedural and a declarative one. Following the latter, knowledge is represented in memory as a database of rules stored in the form of a semantic network. In the procedural path, on the other hand, knowledge is embedded in procedures for action, readily at hand whenever they are required, and it is consequently easier to access.

Anderson (1983) provides the example of an EFL-learner following the declarative path of forming the present perfect in English. S/he would have to apply the rule: use the verb ‘have’ followed by the past participle, which is formed by adding ‘-ed’ to the infinitive of a verb. S/he would have to hold all the knowledge about the rule formation in WSTM and would apply it each time s/he is required to form the tense. This implies that declarative processing is heavy on channel capacity, that is, it occupies the vast majority of WSTM attentional capacity. On the other hand, the learner who followed the procedural path would have a ‘program’, stored in LTM with the following information: the present perfect of ‘play’ is ‘I have played’. Deploying that program, s/he would retrieve the required form without consciously applying any explicit rule. Thus, procedural processing is lighter on WSTM channel capacity than declarative processing.

2.4 Proceduralisation or Automatization

Proceduralisation or Automatization is the process of making a skill automatic. When a skill becomes proceduralised it can be performed without any cost in terms of channel capacity (i.e. “memory space”): skill performance requires very little conscious attention, thereby freeing up ‘space’ in WSTM for other tasks.

3. L2-Acquisition as skill acquisition: the Anderson Model

The Anderson Model, called ACT* (Adaptive Control of Thought), was originally created as an account of the way students internalise geometry rules. It was later developed as a model of L2-learning (Anderson, 1980, 1983, 2000). The fundamental epistemological premise of adopting a skill-development model as a framework for L2-acquisition is that language is considered as governed by the same principles that regulate any other cognitive skill. A number of scholars such as Mc Laughlin (1987), Levelt (1989), O’Malley and Chamot (1990) and Johnson (1996), have produced a number of persuasive arguments in favour of this notion.

Although ACT* constitutes my espoused theory of L2 acquisition, I do not endorse Anderson’s claim that his model alone can give a completely satisfactory account of L2-acquisition. I do believe, however, that it can be used effectively to conceptualise at least three important dimensions of L2-acquisition which are relevant to this study: (1) the acquisition of grammatical rules in explicit adult L2-instruction, (2) the developmental mechanisms of language processing and (3) the acquisition of Learning Strategies.

Figure 1: The Anderson Model (adapted from Anderson, 1983)

The basic structure of the model is illustrated in Figure 1, above. Anderson posits three kinds of memory, Working Memory, Declarative Memory and Production (or Procedural) Memory. Working Memory shares the same features previously discussed in describing WSTM while Declarative and Production Memory may be seen as two subcomponents of LTM. The model is based on the assumption that human cognition is regulated by cognitive structures (Productions) made up of ‘IF’ and ’THEN’ conditions. These are activated every single time the brain is processing information; whenever a learner is confronted with a problem the brain searches for a Production that matches the data pattern associated with it. For example:

IF the goal is to form the present perfect of a verb and the person is 3rd singular/

THEN form the 3rd singular of ‘have’

IF the goal is to form the present perfect of a verb and the appropriate form of ‘have’ has just been formed /

THEN form the past participle of the verb

The creation of a Production is a long and careful process since Procedural Knowledge, once created, is difficult to alter. Furthermore, unlike declarative units, Productions control behaviour, thus the system must be circumspect in creating them. Once a Production has been created and proved to be successful, it has to be automatised in order for the behaviour that it controls to happen at naturalistic rates. According to Anderson (1985), this process goes through three stages: (1) a Cognitive Stage, in which the brain learns a description of a skill; (2) an Associative Stage, in which it works out a method for executing the skill; (3) an Autonomous Stage, in which the execution of the skill becomes more and more rapid and automatic.

In the Cognitive Stage, confronted with a new task requiring a skill that has not yet been proceduralised, the brain retrieves from LTM all the declarative representations associated with that skill, using the interpretive strategies of Problem-solving and Analogy to guide behaviour. This procedure is very time-consuming, as all the stages of a process have to be specified in great detail and in serial order in WSTM. Although each stage is a Production, the operation of Productions in interpretation is very slow and burdensome as it is under conscious control and involves retrieving declarative knowledge from LTM. Furthermore, since this declarative knowledge has to be kept in WSTM, the risk of cognitive overload leading to error may arise.

Thus, for instance, in translating a sentence from the L1 into the L2, the brain will have to consciously retrieve the rules governing the use of every single L1-item, applying them one by one. In the case of complex rules whose application requires performing several operations, every single operation will have to be performed in serial order under conscious attentional control. For example, in forming the third person of the Present perfect of ‘go’, the brain may have to: (1) retrieve and apply the general rule of the present perfect (have + past participle); (2) perform the appropriate conjugation of ‘have’ by retrieving and applying the rule that the third person of ‘have’ is ‘has’; (3) recall that the past participle of ‘go’ is irregular; (4) retrieve the form ‘gone’.

Producing language by these means is extremely inefficient. Thus, the brain tries to sort out the information into more efficient Productions. This is achieved by Compiling (‘running together’) the productions that have already been created so that larger groups of productions can be used as one unit. The Compilation process consists of two sub-processes: Composition and Proceduralisation. Composition takes a sequence of Productions that follow each other in solving a particular problem and collapses them into a single Production that has the effect of the sequence. This process lessens the number of steps referred to above and has the effect of speeding up the process. Thus, the Productions

P1 IF the goal is to form the present perfect of a verb / THEN form the simple present of have

P2 IF the goal is to form the present perfect of a verb and the appropriate form of ‘have’ has just been formed / THEN form the past participle of the verb would be composed as follows:

P3 IF the goal is to form the present perfect of a verb / THEN form the present simple of have and THEN the past participle of the verb

An important point made by Anderson is that newly composed Productions are weak and may require multiple creations before they gain enough strength to compete successfully with the Productions from which they are created. Composition does not replace Productions; rather, it supplements the Production set. Thus, a composition may be created on the first opportunity but may be ‘masked’ by stronger Productions for a number of subsequent opportunities until it has built up sufficient strength (Anderson, 2000). This means that even if the new Production is more effective and efficient than the stronger Production, the latter will be retrieved more quickly because its memory trace is stronger.

The process of Proceduralisation eliminates clauses in the condition of a Production that require information to be retrieved from LTM memory and held in WSTM. As a result, proceduralised knowledge becomes available much more quickly than non-proceduralised knowledge. For example, the Production P2 above would become

IF the goal is to form the present perfect of a verb

THEN form ‘had’ and then form the past participle of the verb

The process of Composition and Proceduralisation will eventually produce after repeated performance:

IF the goal is to form the present perfect of ‘play’/ THEN form ‘ has played’

For Anderson it seems reasonable to suggest that Proceduralisation only occurs when LTM knowledge has achieved some threshold of strength and has been used some criterion number of times. The mechanism through which the brain decides which Productions should be applied in a given context is called by Anderson Matching. When the brain is confronted with a problem, activation spreads from WSTM to Procedural Memory in search for a solution – i.e. a Production that matches the pattern of information in WSTM. If such matching is possible, then a Production will be retrieved. If the pattern to be matched in WSTM corresponds to the ‘condition side’ (the ‘if’) of a proceduralised Production, the matching will be quicker with the ‘action side’ (the ‘then’) of the Production being deposited in WSTM and make it immediately available for performance (execution). It is at this intermediate stage of development that most serious errors in acquiring a skill occur: during the conversion from Declarative to Procedural knowledge, unmonitored mistakes may slip into performance.

The final stage consists of the process of Tuning, made up of the three sub-processes of Generalisation, Discrimination and Strengthening. Generalisation is the process by which Production rules become broader in their range of applicability thereby allowing the speaker to generate and comprehend utterances never before encountered. Where two existing Productions partially overlap, it may be possible to combine them to create a greater level of generality by deleting a condition that was different in the two original Productions. Anderson (1982) produces the following example of generalization from language acquisition, in which P6 and P7 become P8

P6 IF the goal is to indicate that a coat belongs to me THEN say ‘My coat’

P7 IF the goal is to indicate that a ball belongs to me THEN say ‘My ball’

P8 IF the goal is to indicate that object X belongs to me THEN say ‘My X’

Discrimination is the process by which the range of application of a Production is restricted to the appropriate circumstances (Anderson, 1983). These processes would account for the way language learners over-generalise rules but then learn over time to discriminate between, for example, regular and irregular verbs. This process would require that we have examples of both correct and incorrect applications of the Production in our LTM.

Both processes are inductive in that they try to identify from examples of success and failure the features that characterize when a particular Production rule is applicable. These two processes produce multiple variants on the conditions (the ‘IF’ clause(s) of a Production) controlling the same action. Thus, at any point in time the system is entertaining as its hypothesis not just a single Production but a set of Productions with different conditions to control the action.

5. Bridging the ‘gap’ between the Anderson Model and ‘mainstream’ second language acquisition (SLA) research

As already pointed out above, a number of theorists believe that Anderson provides a viable conceptualisation of the processes central to L2-acquisition. However, ACT* was intended as a model of acquisition of cognitive skills in general and not specifically of L2-acquisition. Thus, the model rarely concerns itself explicitly with the following phenomena documented by SLA researchers: Language Transfer, Communicative Strategies, Variability and Fossilization. These phenomena are relevant to secondary school settings for the following reasons: firstly, as far as Language Transfer and Communicative Strategies are concerned, they constitute common sources of error in the written output of L2-intermediate learners. Variability, on the other hand, refers to the phenomenon, particularly evident in the written output of beginner to intermediate learner writing, whereby learners produce a given structure correctly in certain contexts and incorrectly in others. Finally, Fossilization is often produced as a possible explanation of the recurrence of erroneous Interlanguage forms in learner Production. Although these phenomena are accounted for in Anderson’s framework, I believe that a discussion of mainstream SLA theories and research will enhance the reader’s understanding of their nature and implications for L2 teaching. It should be noted that for reason of relevance and space my discussion will be concise and focus only on the aspects which are most relevant to the present study.

5.1 Language Transfer

This phenomenon refers to the way prior linguistic knowledge influences L2-learner development and performance (Ellis, 1994). The occurrence of Language Transfer can be accounted for by applying the ACT* framework since, as Anderson asserts, existing Declarative Knowledge is the starting point for acquiring new knowledge and skills. In a language-learning situation this means drawing on knowledge about previously learnt languages both in order to understand the mechanisms of the target language and to solve a communicative problem. In this section, I shall draw on the SLA literature in order to explain how, when and why Language Transfer occurs and with what effects on learner written output.

a systematic technique employed by a speaker to express his meaning

when faced with some difficulty. Difficulty in this definition is taken to

refer uniquely to the speaker’s inadequate command of the language in

the interaction (Corder, 1978: 8)

A number of taxonomies of CSs have been suggested. Most frameworks (e.g. Faerch and Kasper, 1983) identify two types of approaches to solving problems in communication: (1) avoidance behaviour (avoiding the problem altogether); (2) achievement behaviour (attempting to solve the problem through an alternative plan). In Faerch and Kasper’s (1983) framework, the two different approaches result respectively in the deployment of (a) reduction strategies, governed by avoidance behaviour, and (b) achievement strategies, governed by achievement behaviour.

(3) Inter-/intralingual transfer, i.e. a generalization of an IL rule is made but the generalization is influenced by the properties of the corresponding L1-structures (Jordens, 1977)

(i) Generalization: the extension of an item to an inappropriate context in order to fill the ‘gaps’ in their plans. One type of generalization relevant to the present study is Approximation, that is: the use of a lexical item to express only an approximation of the intended meaning.

(ii) Word coinage. This kind of strategy involves the learner in a creative construction of a new IL word

In the SLA literature, Fossilization (or Routinization) refers to the phenomenon whereby some IL forms keep reappearing in a learner’s Interlanguage ‘in spite of the learner’s ability, opportunity and motivation to learn the target language…’ (Selinker and Lamendella, 1979: 374). An error can become fossilised even if L2-learners possess correct declarative knowledge about that form and have received intensive instruction on it (Mukkatesh, 1986).

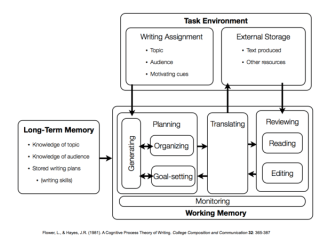

Hayes and Flower’s (1980) model of essay writing is regarded as one of the most effective accounts of writing available to-date (Eysenck and Keane, 1995). As Figure 2 below shows, it posits three major components:

1. Task-environment,

Figure 1: The Hayes and Flower model (adapted from Hayes and Flower, 1980)

The Task-environment includes: (1) the writing assignment (the topic, the target audience, and motivational factors) and the text; (2) The Writer’s LTM, which provides factual knowledge and skill/genre specific procedures; (3) the Writing Process, which consists of the three sub-processes of Planning, Translating and Reviewing.

[(Concept A) (Relation B) (Concept C)]

Finally, the Reviewing processes of Reading and Editing have the function of enhancing the quality of the output. The Editing process checks that discourse conventions are not being flouted, looks for semantic inaccuracies and evaluates the text in the light of the writing goals. Editing has the form of a Production system with two IF- THEN conditions:

applies, e.g. formal sentences, notes, etc. The second is a fault detector for

such problems as grammatical errors, incorrect words, and missing context.

(Hayes and Flower, 1980: 17)

CONDITION 1: (formal sentence) first letter of sentence lower case

CONDITION 2: change first letter to upper case

(Adapted from Hayes and Flower, 1980: 17)

Two important features of the Editing process are: (1) it is triggered automatically whenever the conditions of an Editing Production are met; (2) it may interrupt any other ongoing process. Editing is regulated by an attentional system called The Monitor. Hayes and Flower do not provide a detailed account of how it operates. Differently from Krashen’s (1977) Monitor, a control system used solely for editing, Hayes and Flower’s (1980) device operates at all levels of production orchestrating the activation of the various sub-processes. This allows Hayes and Flower to account for two phenomena they observed. Firstly, the Editing and the Generating processes can cut across other processes. Secondly, the existence of the Monitor enables the system to be flexible in the application of goal-setting rules, in that through the Monitor any other processes can be triggered. This flexibility allows for the recursiveness of the writing process.

Hayes and Flower’s model is useful in providing teachers with a framework for understanding the many demands that essay writing poses on students. In particular, it helps teachers understand how the recursiveness of the writing process may cause those demands to interfere with each other causing cognitive overload and error. Furthermore, by conceptualising editing as a process that can interrupt writing at any moment, the model has a very important implication for a theory of error: self-correctable errors occurring at any level of written production are not always the result of a retrieval failure; they may also be interpreted as caused by detection failure. However, one limitation of the model for a theory of error is that its description of the Translating and Editing sub-processes is too general. I shall therefore supplement it with Cooper and Matsuhashi’s (1983) list of writing plans and decisions along with findings from other L1-writing Cognitive research, which will provide the reader with a more detailed account. I shall also briefly discuss some findings from proofreading research which may help explain some of the problems encountered by L2-student writers during the Editing process.

7.1 The translating sub-processes

The physical act of transcribing the fully formed proposition begins once the graphic image of the output has been stored in WSTM. In L1-writing, transcription occupies subsidiary awareness, enabling the writer to use focal awareness for other plans and decisions. In practiced writers, transcription of certain words and sentences can be so automatic as to permit planning the next proposition while one is still transcribing the previous one. An interesting finding with regards to these final stages of written production comes from Bereiter, Fire and Gartshore (1979) who investigated L1-writers aged 10-12. They identified several discrepancies between learners’ forecasts in think-aloud and their actual writing. 78 % of such discrepancies involved stylistic variations. Notably, in 17% of the forecasts, significant words were uttered in forecasts which did not appear in the writing. In about half of these cases the result was a syntactic flaw (e.g. the forecasted phrase ‘on the way to school’ was written ‘on the to school’). Bereiter and Scardamalia (1987) believe that lapses of this kind indicate that language is lost somewhere between storage in WSTM and grapho-motor execution. These lapses, they also assert, cannot be described as ‘forgetting what one was going to say’ since almost every omission was reported on recall: in the case of ‘on the to school’, for example, the author not only intended to write ‘on the way’ but claimed later to have written it. In their view, this is caused by interference from the attentional demands of the mechanics of writing (spelling, capitalization, etc.), the underlying psychological premise being that a writer has a limited amount of attention to allocate and that whatever is taken up with the lower level demands of written language must be taken from something else.

In sum, Cooper and Matsuhashi (1983) posit two stages in the conversion of the preverbal message into a speech plan: (1) the selection of the right lexical units and (2) the application of grammatical rules. The unit of language is then deposited in STM awaiting translation into grapho-motor execution. This temporary storage raises the possibility that lower level demands affects production as follows: (1) causing the writer to omit material during grapho-motor execution; (2) leading to forgetting higher-level decisions already made. Interference resulting in WSTM loss can also be caused by lack of monitoring of the written output due to devoting conscious attention entirely to planning ahead, while leaving the process of transcription to run ‘on automatic’.

Proofreading theories and research provide us with the following important insights in the mechanisms that regulate essay editing. Firstly, proofreading involves different processes from reading: when one proofreads a passage, one is generally looking for misspellings, words that might have been omitted or repeated, typographical mistakes, etc., and as a result, comprehension is not the goal. When one is reading a text, on the other hand, one’s primary goal is comprehension. Thus, reading involves construction of meaning, while proofreading involves visual search. For this reason, in reading, short function words, not being semantically salient, are not fixated (Paap, Newsome, McDonald and Schvaneveldt, 1982). Consequently, errors on such words are less likely to be spotted when one is editing a text concentrating mostly on its meaning than when one is focusing one’s attention on the text as part of a proofreading task (Haber and Schindler, 1981). Errors are likely to decrease even further when the proofreader is forced to fixate on every single function word in isolation (Haber and Schindler, 1981).

7.4 Bilingual written production: adapting the unilingual model

Writing, although slower than speaking, is still processed at enormous speed in mature native speakers’ WSTM. The processing time required by a writer will be greater in the L2 than in the L1 and will increase at lower levels of proficiency: at the Wording stage, more time will be needed to match non-proceduralized lexical materials to propositions; at the Presenting stage, more time will be needed to select and retrieve the right grammatical form. Furthermore, more attentional effort will be required in rehearsing the sentence plans in WSTM; in fact, just like Hotopf’s (1980) young L1-writers, non proficient L2-learners may be able to store in WSTM only two or three words at a time. This has implications for Agreement in Italian in view of the fact that words more than three-four words distant from one another may still have to agree in gender and number. Finally, in the Transcribing phase, the retrieval of spelling and other aspects of the writing mechanics will take up more WSTM focal awareness.

(2) the acquisition of a skill begins consciously with an associative stage during which the brain creates a declarative representation of Productions (i.e. the procedures that regulate that skill);

(5) the Productions that regulate a skill become automatised only if their application is perceived by the brain as resulting in positive outcomes;

(7) negative evidence as to the effectiveness of a Production determines whether it is going to be rejected by the brain or automatised;

(9) errors may be the result of lack of knowledge or processing efficiency problems;

(10) learners use Language Transfer and Communication Strategies to make up for the absence of the appropriate L2-declarative knowledge necessary in order to realize a given communicative goal. These phenomena are likely to give rise to error.

(11) the writing process is recursive and can be interrupted by editing any time;

(12) the errors in L2-writing relating to morphology and syntax occur mostly in the Translating phase of the writing process when Propositions are converted into language. They may occur as a result of cognitive overload caused by the interference of various processes occurring simultaneously and posing cognitive demands beyond the processing ability of the writer’s WSTM.

These notions have important implications for any approach to error correction. One refers to Anderson’s assumption that the acquisition of L2-structures in classroom-settings mostly begins at conscious level with the creation of mental representations of the rules governing their usage. The obvious corollary being that corrective feedback should help the learners create or restructure their declarative knowledge of the L2-rule system, any corrective approach should involve L2 students in grammar learning involving cognitive restructuring and extensive practice. This entails delivering a well planned and elaborate intervention not just a one-off lesson on a structure identified as a problem in a learner’s written piece.

(2) Errors should be corrected consistently to avoid sending the learners confused messages about the correctness of a given structure.

(3) For Error Correction to lead to the de-fossilization of wrong Productions and the automatization of new, correct Productions, the former should occur in learner output as rarely as possible, whereas the latter should be produced as frequently as possible.

(1) Communication Strategies: in the absence of linguistic knowledge of an L2-item a learner may deploy achievement strategies. As far as lexical items are concerned they may deploy the following strategies leading to error: ‘Approximation’, ‘Coinage’ and ‘Foreignization’. In the case of grammar or orthography learners will draw on existing declarative knowledge, over generalizing a rule (generalization) or guessing;

(4) Avoidance.

As discussed above, errors can also be caused by WSTM processing failure due to cognitive overload. Grammatical, lexical and orthographical errors will occur as a result of learners handling structures which have not been sufficiently automatized, in situations where the operating conditions in WSTM are too challenging for the attentional system to monitor all levels of production effectively. The implications for Error Correction is that learners should be made aware of which types of contexts are more likely to cause processing efficiency failure so that they may approach them more carefully in the future. Examples of such contexts may be sentences where the learner is attempting to express a difficult concept which requires new vocabulary and the use of tenses/moods he has not totally mastered; long sentences where items agreeing with each other in gender and/or number are located quite far apart from each other (not an uncommon occurrence in Italian); situations in which the production of a sentence has to be interrupted several times because the learner needs to consult the dictionary. Remedial practice should provide the learners with opportunity to operate in such contexts in order to train them to cope with the cognitive demands they pose on processing efficiency in Real Operating Conditions.

You must be logged in to post a comment.