Please note: this post was written in collaboration with Steve Smith (co-author with Gianfranco Conti of ‘The Language Teacher Toolkit’ ) and Dylan Viñales (ML teacher at Garden International School)

1. Introduction – The least practised, understood and researched language skill

Since posting my three articles on listening ( ‘Listening – the often mis-taught skill’, ‘So…how do we teach listening?” and “Micro-listening tasks you may not be using often enough in your lessons”) I have been flooded with messages from Modern Language teachers worldwide, all asking me invariably the same question: “So, how do I improve my students’ listening skills ?”.

This has brought home to me the realization that many L2 teachers – and not simply those working within the English-and-Wales educational system – are unsure and anxious about what constitutes effective listening instruction practice. This is not surprising; as Professor Weir and his co-workers (in Weir et al., 2013) point out, of the four language skills listening is by far the “least practised in the language classroom, the least researched and the least understood.” To-date, Listening is not fully integrated in L2 curricula (Macaro, 2003)

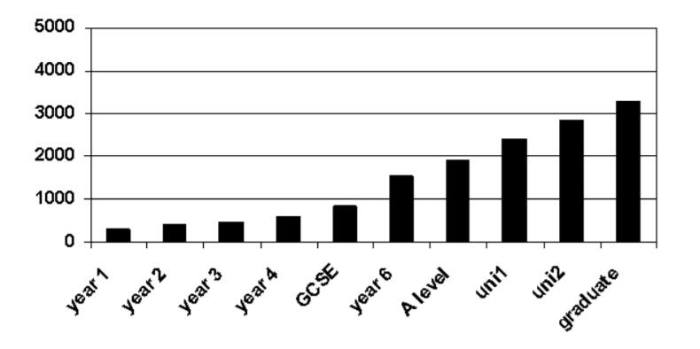

Yet, listening is the most crucial skill in first language acquisition, as it is through the aural medium that humans learn to speak in the first place. According to a number of studies in naturalistic/immersive environments around 45% of language competence is obtained through listening, 30 % through speaking, 15% from reading and 10% only from writing (Renukadevi, 2014) – ironic how the two top skills on this list are also the most neglected by British-trained teachers…

As a teacher trainee – both at Uni and during my teaching practice – and even on my MA TEFL (where Professor Weir was ironically one of my lecturers) I was taught close to nothing on how to teach listening; for many years I simply taught listening as I had been taught it myself at school or as prescribed by the course-book in use. CPD on listening was pretty useless and centred on facilitating student guesswork, rather than providing teachers with guiding principles on how to enhance learner listening skills. This is, to my knowledge, what most teachers do and that is why Steve Smith and I devoted an entire chapter of ‘The Language Teacher Toolkit’ to aural skills in an attempt to address some of the most important challenges posed by Listening instruction.

1.1 A ‘trilogy’ about Listening Instruction: goals and expected outcomes

This is the first in a ‘trilogy’ of posts written in collaboration with MFL guru Steve Smith and Garden International School colleague Dylan Viñales. The objectives of these posts are to (1) Discuss the mechanisms underlying the way humans process and interact cognitively and affectively with aural input and listening instruction (in PART 1); (2) identify the shortcomings of much current Listening instructions (PART 2 – to be published next week) and (3)Examine the implications for the classroom (more superficially in PART 1 and in much greater depth and detail in PART 3) and discuss the approach that I have undertaken (not always succesfully) in my own classroom practice in collaboration with some colleagues at Garden International School (Kuala Lumpur).

PART 1 – Identifying the challenges listening-skill instruction poses to teachers and learners

In this post I will narrow down the focus and concentrate on novice-to-intermediate learners discussing how, based on Skill-acquisition models of language learning and my own classroom experience teachers may be able to enhance their students’ proficiency. I will start with a concise reminder of how L2 learners interact with L2 aural input both cognitively and affectively

2. Some important facts about how human interact with and process aural input

2.1 Top-down and Bottom-up processing

There is a general consensus amongst researchers that the human brain comprehends aural input by applying synergistically two types of processing: Top-down and Bottom-up. Top-down processing involves applying our knowledge of the world (schemata), all we know about a specific subject, topic, situation or group of people in the understanding of input which relates to that subject, topic, situation or group of people (Macaro, 2013). For instance, in listening to a love song in a foreign language we have a whole set of expectations about what it is going to be about and we can make educated guesses about what line is going to come next even if we do not understand each and every word – purely based on our previous experiences of listening to love songs.

Brown (2007) identifies the following Top-down skills which he labels Listening macro-skills (for conversational discourse):

- Recognize cohesive devices in spoken discourse.

- Recognize the communicative functions of utterances, according to situations, participants, goals.

- Infer situations, participants, goals using real-world knowledge. (pragmatic competence)

- From events, ideas, etc., described, predict outcomes, infer links and connections between events, deduce causes and effects, and detect such relations such as main idea, supporting idea, new information, given information, generalization, and exemplification.

- Distinguish between literal and implied meanings.

- Use facial, kinesic, body language, and other nonverbal cues to decipher meanings.

- Develop and use a battery of listening strategies, such as detecting key words, guessing the meaning of words from context, appealing for help, and signaling comprehension or lack thereof. (p.308)

Bottom-up processing, on the other hand, involves interpreting the aural input by analysing basic linguistic features such as recognizing word boundaries, stress and intonation, grammatical word-classes (nouns, verbs, etc.), systems (tenses, agreement, pluralisation, etc.).Below is Brown’s (2007) list of listening comprehension micro-skills (for conversational discourse) (p. 308)

- Retain chunks of language of different lengths in short-term memory

- Discriminate among the distinctive sounds of [the target language]

- Recognize English stress patterns, words in stressed and unstressed positions, rhythmic structure, intonational contours, and their role in signaling information.

- Recognize reduced forms of words.

- Distinguish word boundaries, recognize a core of words, and interpret word order patterns and their significance.

- Process speech containing pauses, errors, corrections, and other performance variables.

- Process speech at different rates of delivery.

- Recognize grammatical word classes (nouns, verbs, etc.), systems (e.g., tense, agreement, pluralization), patterns, rules, and elliptical forms.

- Detect sentence constituents and distinguish between major and minor constituents.

- Recognize that a particular meaning may be expressed in different grammatical forms. (308)

The two processing modes ‘work’ together, concurrently and synergistically to help making sense of what we hear. Going back to the love song example, for instance, my previous experience of listening to love songs by singer ‘X’, will give rise, in listening to one of her songs, to a set of expectations about what the song is about (top-down processing). The song’s title and the video-clip that accompanies it will expand the set of predictions I am building. My predictions will be confirmed or discarded by the words I will be able to identify (bottom-up processing) whilst at the same time helping me make sense of the words I do not understand. It should be noted that, in my attempt to identify a challenging word I may use its sound (phonological level), its word-class (morphological level), its position in the sentence (syntactic level) – amongst other cues- in order to recognize or make sense of it.

Skills 1, 5 and 7 on the above micro-skills list (in bold) are particularly important as skill 1 speeds up processing, freeing up cognitive space for our brain (working memory) to focus on meaning and skill 5 helps us make sense of what we hear by segmenting the aural input. Without segmentation aural input is perceived by the students as an unintelligible fast-running flow. The inability to segment input, linked with poorly developed decoding skills, is the greatest obstacle to understanding for many novice-to-intermediate learners and the main reason of learner disaffection and low self-efficacy vis-à-vis listening. Hence the need that I reiterate ad nauseam in my blogs for systematic and extensive decoding-skill instruction (i.e. the ability to transform graphemes into phonemes, letters into sounds) from the very early days of L2 instruction (read my post here:Micro-listening tasks you may not be using often enough in your lessons”).

As for skill 7, it is paramount for students to get used to different speeds of delivery in order to train their aural-input processing skills – reading the same text several times at different speeds, from slower to nearnative speed or viceversa pays dividends in this regard, in my experience.

As I will point out in PART 2, very few – if any at all – of the skills identified by Brown (2007) are explicitly and systematically addressed by curriculum designers and course-books in use in most UK educational settings. Yet, they provide teachers with a very useful blueprint for listening instruction by isolating the core macro- and micro-skills; a much needed framework, considering that much L2 listening instruction is currently designed and conducted in an unstructured and in same cases, haphazard fashion. I strongly believe that by integrating the core skills amongst those identified by Brown (2007) in our curriculum and explicitly teaching them to our students we can significantly enhance the impact of listening instruction.

2.2 Processing capacity

Working Memory (WM) Processing capacity is a very important determinant of how effectively and efficiently our students comprehend aural input. As Cornell professor Morten Christiansen and his Warwick Univeristy colleague Nick Chater put it in a recent ground-breaking paper (Chistiansen and Chater, 2016):,“the ability to quickly process linguistic input […] is a strong predictor of language acquisition outcomes from infancy to midde childhood.”

This is because Working Memory having very limited cognitive space available for the processing of any incoming information, if it is performing too many tasks at the same time it will experience overload and that information will be lost due to divided attention. In order to create more cognitive space, the brain tends to automatize lower order skills (e.g. decoding skills; segmenting aural output; recognizing grammatical word class) so that it has more processing capacity to devote to higher order cognitive skills such as analyzing meaning, building inferences, etc. Hence, without enabling our students to automatise the micro-skills on Brown’s (2007) list, their brain will never manage to have sufficient cognitive space to process higher level listening tasks.

2.2.1 A few important facts about Working Memory

As concisely laid out in my post on Working Memory (here), WM is a buffer between the world and Long-Term Memory; a ‘device’ in our brain which processes any incoming information and, should the rehearsal of such information be successful, commits it to Long-term Memory (where it will be stored for ever). As you read this post, your WM is processing my words interpreting them based on the existing information in your Long-Term Memory. WM activates information through chains of association triggered by the sound, meaning, grammar, etc. of whatever input it processes. So, for example, if I hear the word ‘dog’, everything to do with the notion of dog will receive electrical impulses along the brain neural network; the language items more strongly connected in our personal processing history will receive the greatest activation and will be easier to recall.

Models of Working Memory posit a system made up of two slave systems, the Visio-spatial Scratchpad which stores images (including language characters from ideographic languages, e.g. Chinese) and a Phonological loop which stores the sounds we hear and consists of two parts: the phonological store (inner ear) and the articulatory control process (inner speech). A third component, the Central Executive, is in charge of orchestrating the functioning of the two slave systems and of managing the flow of data to and from Long-Term Memory.

Much of our students’ success at comprehending L2 aural input will hinge on how efficiently and effectively Working Memory processes such input. This is because:

- Working memory storage is fragile – it takes a minimum distraction for the information being processed to be lost (forgetting from divided attention);

- Working memory storage capacity is very limited: 7+/- 2 digits only according to Miller (1965), less according to others (Christiansen and Chater, 2016). The Phonological Loop (more precisely: the phonological store or inner ear) can only store only about 1 to 2 seconds of speech at any one time (some say even much less – 100 milliseconds). This has three important implications: (a) that individuals genetically endowed with a larger working memory span will have an advantage; (b) that the ability to store language will be a function of how effectively the students can decode and pronounce the sounds they hear (since the faster they can reproduce the sounds the smaller the space in the phonological store they will occupy) – the argument for ultra-emphasizing decoding-skills instruction; (c) whatever information ‘X’ students hold in Working Memory as they process aural input will be lost when new incoming information ‘Y’ arrives, which means that students have an extremely short time frame to process what they hear before it is overwritten by new input. As Christiansen and Chater (2016) posit, the brain speeds up language processing by ‘chunking’ linguistic material into a hierarchy of increasingly abstract representational formats, from phonemes to syllables, to words, phrases, sentences, discourse. ‘Chunking’ prevents the information held in Working Memory from being erased for ever from our brain (to learn more about chunking read here)

- The brain works like Google – A given language item’s processing history will determine (a) how easily it will be processed and comprehended and (b) the extent to which it will facilitate or slow down comprehension. Why? An analogy with Google search will help illustrate what I mean: this morning I as I was typing into the Google search box ‘we don’t’ a number of options appear in a hierarchical arrangement: ‘ we don’t talk any more’, ‘we don’t want another hero’, etc. In other words Google statistically predicted the sentence I was looking for based on Google users’ behaviours to-date or, when I searched through my own Google account, based on my own searching history to-date. The brain operates similarly, based on our individual processing history with specific language items; so, just like Google, on hearing the words ‘ we don’t’ our Working Memory will automatically activate any words , phrases, sentences containing those three words that we have heard more frequently; the ones heard most frequently will receive the strongest activation, the ones processed least frequently, the weakest. Other cues/constraints from the environment (e.g. the topic we are talking about, the facial expressions of our interlocutor, etc.) will affect the activation of those words/phrases/sentences too, to a certain extent. (Macaro, 2003).

The most important implications of the above are that:

(a) learners need to practise a lot more listening than they typically do at present, day in, day out. This is fundamental. Ideally, teachers would put a lot of effort in promoting independent listening outside lesson time for pleasure or at least through homework;

(b) again: listening micro-skills, especially decoding skills, must be taught (I will deal with this point more extensive in my next post)

(c) the core language items must be recycled extensively through listening/speaking across as many contexts as possible -not simply reading and writing – for the reasons outlined in point 3 above (ease of retrieval depending on an individual’s processing history of each language item acquired).

2.3 Differences between audio-recording-based listening comprehension and real-life listening

In real-life conversation and whilst watching audio-visual material paralinguistic features such as visual expressions and other gestures render aural comprehension easier as compared to listening to a recorded text. Moreover, in conversational listening the listener benefits from repetitions, redundancies, hesitation and pauses in the input which easify comprehension. The typical listening comprehensions we give our students do not offer these facilitative features in their input. This brings into questions the validity of audio-recording-based listening comprehensions (especially in high stake tests and national examinations) as they do not necessarily prepare students for real-life communication. These isssues bring us to the next point.

2.4 Listenership

Listenership refers in the literature to the ability to comprehend our interlocutor(s)’ input and respond to it in real time in the context of a conversational exchange. As it is obvious, it requires the acquisition of an altogether different set of skills to the ones we deploy in ‘passive listening’ activities such as the execution of a listening comprehension task). Listenership thus refers undoubtedly to the most important set of language skills an autonomous L2 speakers requires in the real world, whether as a tourist finding their way around Paris or as a businesswoman negotiating a deal in a video-conference. Listenership can only be acquired through masses of oral communicative practice

2.5 The Listening-as-modelling vs the Listening-to-test-comprehension approaches

In the early stages of L1 acquisition new language items are picked up through highly simplified aural input which is produced by parents/caregivers at a slower speech rate than in normal native-speaker-to-native-speaker communication; repetition and use of gestures to facilitate comprehension are frequent too. Caregiver speech rate increases significantly as the child’s processing ability increases.

The same often happens when,say, an English Native/Expert speaker interacts with a much less proficient L2 speaker. For instance, yesterday, as I was talking to an L2 Italian speaker I found myself talking to them pretty much in the same way as I used to talk to my daughter when she was two, repeating key words several times with greater emphasis, exaggerating facial expressions, pointing at objects around me and often producing ungrammatical utterances to facilitate understanding on their part (e.g. leaving the verb unconjugated and using discourse markers only to indicate the future).

A slower speech rate, lots of visual cues (whether through images and gestures), simplified (comprehensible) input, lots of repetition and translation (yes- translation!) facilitate the new-language modelling function that aural input performs in the early phases of language acquisition; it provides speakers with poor aural-input processing ability with more time and greater chances to notice new linguistic features as segmentation (identifying the boundaries of words) is easier to perform. This is important, as noticing a new phoneme, word or morpheme is thought to mark the beginning of its acquisition (Schmidt, 1990, 1993,1994,1995).

Smith and Conti (2016) drew a clear distinction between the Listening-as-modelling and the Listening-for-testing-comprehension or ‘Quiz approach’ to listening-skill instruction. The former concerns itself with ensuring that L2 students learn through every single aural activity staged; the latter, sadly the more common approach in the typical UK classroom, concerns itself with providing practice in picking out details in order to answer a few questions on a recorded text heard two or three times – hardly an effective way to model new language. As I will discuss in the sequel to this post, to be published next week, the predominance of the ‘quiz approach’ remains to-date the root cause of the inefficacy of much listening instruction; as I shall argue there, listening-comprehension tasks can indeed play an important role in listening-skills acquisition, but only provided that much listening-as-modelling as occurred before.

By listening-as-modelling I do not simply mean the very common practice of asking the students to repeat a word or short phrase a couple of times after the teacher utters them since, as mentioned above, speech stays in working memory for too short a time for that sort of repetition to lead to acquisition. Also such practice models short phrases, not sentence building or more extensive and complex discourse.

Reading aloud is one example of listening-as-modelling that is indeed practised in a number of UK learning settings. In our book (Smith and Conti,2016) Steve and I provide a strong rationale for using it and there is mounting evidence (e.g. Seo, 2014) that even a few minutes per lessons can significantly impact speaking proficiency and willingness to communicate.

And how about the teacher using the target language in most of the lessons? Not an uncommon occurrence in UK classrooms, after all…Well, it may be argued that teacher fronted talk in the target language does constitute Listening-as-modelling when the target language is used to explicitly model and recycle new language and to deliberately promote noticing (as in the example Steve Smith provides in our books in the section on target language use). However, in 25 years of lesson observations in British schools, I have indeed seen target-language teacher talk being used effectively to facilitate comprehension, but not to explicitly model specific language items through systematically recycled ‘patterned’ input. The teacher’s aural input is usually spontaneous – not a bad thing; however, when teacher contact time is limited (one or two hours a week), this kind of aural input is unlikely to substantially enhance acquisition – at least in my experience. I do believe, however, that in immersive or other input-rich L2 environments such practice can indeed significantly impact learning.

As I reserve to discuss in greater depth in my next post, Listening-as-modelling includes instructional activities which focus the learners on pronunciation and decoding skills, in an effort to facilitate phonological processing and segmentation; on predictive strategies; on the identification of word-classes and systems; on the understanding of syntax and sentence building; on the development of aural-input processing; on building metacognition vis-à-vis the listening process. Listening comprehension is built in such activities but in a way that scaffolds the modelling.

2.6 The affective response

So far we have looked at the way learner cognition responds to aural input. How about the affective response? In my experience, the ‘quiz’ approach, especially in the absence of adequate training in inference strategies and differentiation (difficult when all students listen to the same track at the same pace from the same input source) has led to a generation of disaffected listeners. This is tragic considering the wealth of L2 audio-visual material available on the web. However, as long as listening instruction limits itself to quizzes it will elicit guesswork and guesswork will rarely build learner self-efficacy, a crucial precursor, as Smith and Conti (2016) argued, for the development of intrinsic motivation.

For self-efficacy vis-à-vis aural-input-processing to be fostered in the classroom, the learners must be adequately prepped for any listening task which may be perceived as a test (e.g. a listening comprehension) by a few listening-as-modelling activities which recycle very similar lexical material and phonetic, grammatical and syntactic patterns so as to scaffold success. In the sequel to this post (PART 2) I will explain how I attempt to do it.

3. Conclusions to Part 1: first set of implications for teaching and learning and issues to be tackled in Part 2

The above discussion has huge implications for listening-skills instruction. Please note that each of the point below will be treated more extensively and with several examples in my next post.

(1) students need tons of listening practice which aims at speeding up processing (i.e. automatising ‘chunking’) – I will discuss how in the sequel to this post. A culture of listening-for-learning as opposed to listening-for-testing must be established in the classroom since the very early days of instruction through a variety of activities which aim at modelling comprehensible input and elicit a positive affective response (e.g. jigsaw listenings using songs; sentence building mats, watching short movies with subtitles; story-telling with visuals). Moreover, speed of delivery should be reduced and varied (in a formative way) and linguistic content should be simplified with repetitions added in if necessary to facilitate comprehension. Transcripts and translations (e.g. parallel texts) could be used to scaffold the modelling process (this, too, will be discussed in my next post).

(2) students need EXTENSIVE practice in pronunciation and decoding skills from the very beginning of their L2 learning experience (e.g. through listening-micro-skills enhancers , partial transcription tasks and even short dictations ). I use them a lot in my lessons and students find them useful and fun. The set of new phonemes and corresponding graphemes taught should not, in my experience, amount to more than three or four per lesson.

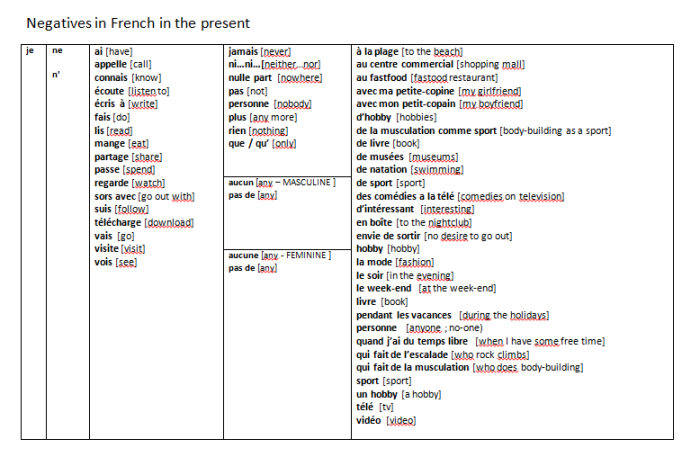

(3) listening practice must recycle the target lexical material as much as possible in order to facilitate ‘chunking’ and future ease of retrieval from Long Term Memory. This may call for strategies like narrow listening, i.e. the administration of a series of listening texts which are very similar in terms of lexical, grammatical and syntactic content, thereby requiring increasingly less inferences on the part of the student-listener. At this link you will find an example of L2-French Narrow Reading texts which can be used for Narrow Listening, too. Again, narrow listening is something I used a lot in my lessons, usually preceded by a battery of narrow reading texts containing the same linguistic material

(4) the target words and set phrases (especially if they are part of an Examination Board core vocabulary) must be recycled through the aural medium in as many different semantic, grammatical and phonetic contexts as possible in order to create a processing history which will facilitate comprehension in the long run (see 2.2.1 above).

(5) The development of listening-skills, especially those underlying the ability to listen and respond to aural input (listenership) goes hand-in-hand with the development of oral communication skills. Hence, oral communicative activities (e.g. student-to-student conversations) should feature as often as possible in lessons. In order to ensure the type of recycling envisaged in point 3 and 4 above, such oral activities should include a substantial amount of structured activities ‘forcing’ learners to produce the target material (e.g. oral translations; role plays with prompts; cued picture tasks).

(6) listening comprehension tasks should be used almost exclusively as ‘plenary’ activities or tests to be carried out after much modelling of the linguistic material they contain has occurred. This will be perceived by the learners as much fairer than being asked to perform guesswork on an aural text containing lots of unfamiliar language and will enhance their chances to experience success, which will feed into their self-efficacy as L2- listeners. Teachers with good pronunciation may want to read the transcripts themselves rather than play the recording with less adept student-listeners, to facilitate processing. Please note that the Listening-as-modelling I envisage does include a comprehension component.

(7), curriculum planners may want to explicitly and systematically address in their long-/medium- and short-term planning the existing listening macro-skills and micro-skills taxonomies (e.g. the one by Brown, 2007, above). This would provide the curriculum (e.g. Schemes of Work) with a structure and a specific set of objectives to focus on – surely a massive improvement over the haphazard way in which listening instruction is currently carried out. I use pre-listening tasks mainly as a vehicle for the modelling of the inference/predictive strategies envisaged by Brown’s (2007) and decoding skills (e.g. by reinforcing challenging sounds contained in the target text which may impair comprehension). I tend to use tasks involving focus on micro-skills in the in-listening activities I stage (three or four per task), jigsaw listening, segmentation tasks (identifying word boundaries) and patterns/system identification tasks (identifying word classes, tenses etc.), being my favourites. I use post-listening tasks, instead, for metacognitive reflection or critical listening (see my next post).

(8) Finally, as part of the Listening-for-learning approach, teachers ought to exploit any given recording much more than it is currently done by course-books. Carrying out three or four different activities with the same texts plus a pre-listening and a post-listening one will enhance the chances that the target vocabulary and linguistic features in the listening piece will be retained.

In a nutshell, the current teaching of listening skills does, in my opinion, need a drastic shake-up. The most important change language educators ought to implement is one of mindset, from a culture of listening-for-testing to one of listening-as-learning. This entails more Listening-as-modelling practice as well as more focus on Listenership, which in turns implies more oral interaction in the classroom.This change in orientation – which does not rule out using listening comprehesion tasks, as I hope it is clear from the above discussion – is fundamental if we want to equip the 21st century L2 learners with the skill set required to become effective autonomous listeners.

3.1 What I will write about in PART 2

In my next post I reserve to delve deeper into the above implications and to discuss the ‘how’ I implement them as part of my daily classroom practice. I shall also point out the most common shortcomings of typical listening-skills instruction in the UK as identified by Steve, Dylan and myself, discussing the way we have addressed them (not always successfully) throughout the last academic year in our classroom practice (at Garden International School, Kuala Lumpur).

Part 2 and 3, the next posts in the ‘trilogy’, will concern itself with the following shortcomings of listening instruction, delving in much greater depth into the day-to-day strategies I have implemented in my classroom practice to address them in collaboration with my colleague Dylan Vinales at Garden International School (Kuala Lumpur):

- Insufficient aural/oral skills practice

- Poor curriculum design/lesson planning

- Ineffective sequencing and integration with other skills

- Insufficient ‘patterned’ recycling

- Inadequate exploitation of listening resources

- Lack of differentiation

- The ‘quiz approach’

- Insufficient use of listening-as-modelling

- No systematic and explicit focus on the development of aural-input processing ability

- Insufficient practice in listenership skills

Please note: To find out more about Steve Smith and Gianfranco Conti’s ideas on the above, get hold of their book ‘The Language Teacher Toolkit’,

References

Brown, D. H. (2007). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy. White Plains, NY: Longman.

Christiansen, M.H. & Chater, N. (2016). Creating language: Integrating evolution, acquisition, and processing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Macaro, E (2003). Teaching and Learning a Second Language A Guide to Recent Research and Its Applications. London:Continuum.

Richards, J. C. (1983). Listening comprehension: Approach, design, procedure. TESOL Quarterly, 17, 219-239.

Rukadevi, D. (2014). The Role of listening in language acquisition; the challenges and strategies in teaching listening. International Journal of Education and Information studies, 4, 59-63 http://www.ripublication.com/ijeisv1n1/ijeisv4n1_13.pdf

Seo (2014) Does reading aloud improve foreign language learners’ speaking ability. GSTF International Journal on Education (JEd) Vol.2 No.1, June 2014

Smith and Conti (2016). The Language Teacher Toolkit. Amazon.

Weir, C J, Vidakovic, I and Galaczi, E D (2013). Measured Constructs: A history of Cambridge English language examinations 1913-2012. Studies in Language Testing 37

You must be logged in to post a comment.