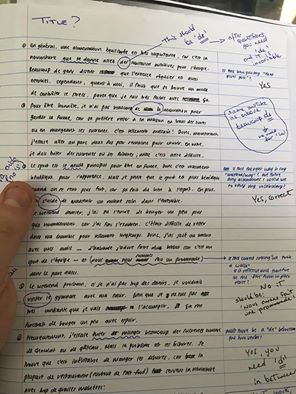

In a couple of previous posts I briefly touched on theories of motivation and on how they can be tapped into to raise student achievement. In particular I concerned myself with a relatively unknown and yet powerful catalyst of motivation, self-efficacy, or expectancy of success, which, if nurtured regularly and adequately in the classroom can majorly impact learning. In this post I will very concisely outline the main principles underpinning other influential motivational theories and how I deploy them in my every day teaching in an attempt to enhance my students’ motivation.

Here is a very minimalistic overview of 8 of the 20 theories of motivation I brainstormed before writing this article. Please note that their tenets and implications for the classroom have been overly simplified; hence, if you are keen to apply them to your specific teaching context, you may want to find out more about them.

- Cognitive dissonance

Cognitive dissonance occurs when there is an unresolved conflict in our mind between two beliefs, thoughts or perceptions we hold about a given subject. The level of tension resulting from such conflict will be a function of:

- How strong the conflict is between the two dissonant thoughts;

- How important the issue they relate to are to a specific individual or group;

- How difficult it is to rationalize (justify through logical or pseudo-logical reasoning) the dissonance.

Cognitive dissonance is a very powerful motivator which, as I shall discuss in a future post, is often used in transformational change programs both in the business and educational world. The reason why it is so powerful is because, when used effectively, Cognitive dissonance creates a sense of discomfort in an individual which in order to be resolved results in one of two outcomes:

- The individual changes behavior (possibly replacing the existing behavior with the newly modelled one);

- The individual does not adopt the new behavior and justifies his/her behaviour by changing the conflicting cognition created by the new information, instead.

Implications for the classroom: Whenever you want to change a student’s attitude, first identify the beliefs at the heart of that attitude; when you have a fairly clear picture induce cognitive dissonance by producing powerful information and arguments which counter those beliefs. The degree of cognitive dissonance should be as high as possible for the attitudinal change we purport to bring about to be effective. For example, when dealing with a misbehaving child, to simply tell them off for what they did will be way less effective than raising their awareness of the ways their conduct affected others negatively and explaining why is morally/ethically wrong. Or, to impose a new methodology to one’s team of teachers by saying it is more effective than the one currently in use by merely providing statistics from a few research studies which point to its greater effectiveness will not be as powerful as explaining to them why the old approach is failing the target students and the new can more effectively address the identified shortcomings. Another example in the realm of language learning: many foreign language students in England hold negative views about the country(i-es) where the target language is spoken. If one wants to change such attitudes one may want to first find out what beliefs are at the root of those attitudes (e.g. are they xenophobic stereotypes?); then in a lesson or series of lesson (at the beginning of the year, maybe?) provide objective and solid reasons to prove that those beliefs are indeed false using supporting evidence which will resonate with the students’ sub-culture, thereby creating cognitive dissonance. Research suggests that over-using statistics may be detrimental and that engaging the target students in a discussion on the issues-in-hand after the new information has been provided, will enhance the chances of attitudinal change to occur. This process may induce the learners to restructure their cognition.

- Drive reduction theory

This theory is centred on the notion that we all have needs that we attempt to satisfy in order to reduce the tension or arousal they cause. The internal stimuli these needs produce are our main drives in life. There are Primary drives which refer to basic needs (food, sleep, procreation, etc.) and Secondary drives which refer to social identity and personal fulfillment.

As we act on our needs we are conditioned and acquire habits and subconscious responses. So, for example: when a child needs to feel good about himself, he may recite a poem, sing a song, perform a dance or other ‘feats’ to his parents knowing he is going to get some recognition. Whenever he needs recognition in other contexts, this individual will possibly use the same tactics in order to get the same response from any other figure of authority – including teachers.

When the driven action does not satisfy his needs or the enacting of drives is frustrated, negative emotions (e.g. anxiety) arise. To go back to the previous example: if the boy is looking for a chance to show off to an authority figure his ‘skills’ but he is not given the opportunity to do so, he will feel frustrated, angry and/or unappreciated – a very common scenario in school, often dismissed as the child being ‘naughty’ or ‘unruly’.

Implications for the classroom: find out what drives your students, especially the difficult ones. Instead of approaching the problem by ‘punishing’ them, have a one-on-one chat with them and try to discover what is that they find fulfilling and see if you can find opportunities in your lessons for them to enact their drives. For instance, if you have a student passionate about drama who does not seem to enjoy language learning, ask them to contribute their acting skills by myming vocabulary or sentences in lessons or setting up a mini-production in the target language.

- Attribution theory

When we make a mistake or ‘fail’ at something we tend to go through a two-step process. We first experience an automatic response involving internal attribution (i.e. the error is our fault); then a conscious, slower reaction which seeks to find an alternative external attribution (e.g. the error is due to an external factor). This is because we all have a vested interest in ‘looking good’ in our own eyes – a sort of survival mechanism. This type of response, however, is unlikely to lead to self-improvement, as it results in an individual not addressing the real cause of their error/bad performance in the future. Roesch and Amirkham (1997) found that more experienced and successful athletes made more self-serving attributions which lead to identifying and addressing the internal causes of their performance errors.

Implications for the classroom: when dealing with students who complain about not progressing because the subject, skill or task is too hard for them, show them – where applicable – that the reasons why they are not improving is not intrinsic in the nature of that subject, skill or task , but has more to do with other factors under his/her control (e.g. the study habits, such as lack of systematic revision). This will create cognitive dissonance and may have an impact on their attitude, especially if they are shown strategies that may help them improve in the problematic area(s) of their learning. The afore mentioned research by Roesch and Amirkham (1997) and their findings could be drawn upon and discussed with your students to reinforce the point; I often do, citing the example of famous athletes the students admire and pointing out how they learn from their mistakes by watching videos of themselves playing a match over and over again or asking peers/experts for feedback in order to identify and address their shortcomings.

- Endowed progress effect

When people feel they have made some progress towards a goal, they will feel more committed towards its achievement. Conversely, people who are making little or no progress are more likely to give up early in the process. In my work with very low achieving ‘difficult’ students when I operated in challenging inner-city-area schools,sitting with them at the beginning of a task and guiding them through open questioning often ‘did the trick’ where threatening them with sanctions had failed miserably.

Implications for the classroom: Whatever the task you engage your students in, ensure that they all experience success in the initial stages. This may call for two approaches which are not mutually exclusive: (1) design any instructional sequence in a ‘stepped’ fashion, with ‘easy’ tasks that become gradually more difficult; (2) provide lots of scaffolding (support) at the initial stages of teaching.

- Cognitive Evaluation Theory

When looking at a task, we assess it in terms of how well it meets our need to feel competent and in control. We will be intrinsically motivated by tasks we believe fall in our current level of competency and ‘put off’ by those which we deem we will do poorly at. This issue is often more about self-perception of one’s levels of competency than objective truth.

Implications for the classroom: we need to ensure that before engaging students in challenging tasks that they may perceive as being beyond their levels of competence we prepare them adequately, cognitively and emotionally. For instance, in language learning, before carrying out a difficult listening comprehension task, students should be exposed several times to any unfamiliar vocabulary or other language item contained in the to-be-heard recording so as to facilitate the task. Moreover, modelling strategies that may facilitate the tasks and giving them the opportunity to experience some success in similar tasks through those very strategies may increase their sense of self-efficacy; this will give them greater expectancy of success and a feeling of empowerment which will feed into their sense of competency and control.

Another important implications relate to the way we design the curriculum and assessment. For effective progression from a lower level to a higher one to be possible, students must be given plenty of opportunities to consolidate the material processed at the lower level before moving on. This does not often happen in courses which rely heavily on textbooks. For instance, in most of the institutions I have worked in over 25 years of teaching, I was asked to teach a unit of work every six-seven weeks, a totally unrealistic pace when contact time is limited to one or two hours a week. The result: the weaker children are usually left behind.

- Self-determination theory; Intrinsic and Extrinsic motivation.

Individuals differ from one another in terms of PLOC (personal locus of causality). Some will feel that their behavior is self-determined; they are the initiators and sustainers of their actions and their PLOC will be internal. Others will see external forces as determinants of their lives; coercing them into actions. These people’s PLOC will be external. The internal locus is connected with intrinsic motivation, whilst the external locus is connected with extrinsic motivation.

Extrinsic motivation is when one is motivated by external factors, such as rewards, social recognition or fear of punishment. This kind of motivation focuses people on rewards rather than action.

Intrinsic motivation, on the other hand, refers to the desire to do things because we enjoy doing them, hence it is a stronger motivator than Extrinsic motivation. Three needs lead to intrinsic motivation:

- Being successful at what we do (i.e. I enjoy French because I am good at it);

- Being connected with others (i.e. I love my French class because I have bonded well with the rest of the class)

- Having autonomy (see below)

An important factor leading to Intrinsic Motivation creation is providing learners with the oppportunity to develop effectance. Effectance refers to one of the 3 points made above (being successful at what we do) and is given rise to when the learner accomplishes success at something that they perceive challenging and falling in what Deci (1997) terms ‘Optimal zone of development’ – i.e.: a task that it is perceived as difficult enough to be challenging but within the stretch of the learner’s ability. Effectance does not arise when we simply give students ‘easy’ work; that is why the ‘easy wins’ strategy often fails with students with poor intrinsic motivation; students are not stupid, they know you are dumbing down the work to make them feel good and the ensuing praise will not affect their self-regard as learners of your subject.

Self-determination theory assumes that there are individuals for whom a feeling of being in control of their life and responsible for their actions is very important for their personal fulfillment and, consequently, for their motivation.

Implications of Self-Determination theory for the classroom: it may be useful to identify which students in your classes have an internal or external PLOC. In my experience this is not difficult. Once identified the internal PLOC of the target individuals, it is very important to cater for their self-determination needs and grant them a degree of autonomy in and ownership over their learning. E.g.: when staging a reading session in the classroom; carrying out a project; asking students to practise vocabulary online, let them choose how to go about it (whilst setting some guidelines for the sake of consistency). People with high internal PLOC thrive in self-directed learning tasks and contexts; teachers must endeavour to exploit to the fullest this personality trait’s greater potential for autonomy in L2 learning. People with a high external PLOC will need more praise, direction from and a sense of accountability to teachers and caretakers.

Implications of Intrinsic and Extrinsic motivation theory: Pretty obvious. The main ones: (1) make lessons as enjoyable as possible and make them experience EFFECTANCE regularly in your lessons, as this may help boost their intrinsic motivation; (2) Plan every single one of your lessons with the following questions in mind: ‘How can I make sure that every student goes out of my lessons feeling they have progressed?; (3) foster connectedness in the class by creating a team spirit and a sense that the whole class is working towards the same goal and that every student feels comfortable working with everyone else (e.g. make sure that people do not work with the same partners all the time when staging group work); give plenty of opportunities for positive peer feedback (e.g. get students’ to celebrate other students’ achievements). (4) Show them the benefits of learning the TL for their future job prospect, personal growth, etc. and of every activity you stage in lessons in terms of learning benefits; use praise as a means to validate their efforts but ensure that you do not over-praise or it will lose its motivational power (most students can sense when you are just trying to bribe them with compliments; this may engender complacency and even loss of motivation in the long-run).

There is a myth circulating amongst some educators these days (including some of my colleagues) that Extrinsic motivation should not be tapped into as a strategy to encourage students to improve. However, there is no sufficient credible evidence that Extrinsic Motivation is detrimental to learning to do away with it; on the contrary, research shows consistently that extrinsic motivation, when not overused and deployed in synergy with some of the other strategies discussed in this post, can eventually bring about Intrinsic motivation. Example: a student that does not enjoy French may, through experiencing a sense of effectance and obtaining consistent (thoroughly deserved and proportionate) praise and rewards become more appreciative of the subject, especially if she is experiencing steady growth in her mastery of the language and feels connected and supported by his peers.

It is self-evident that using Extrinsic motivation will work with certain individuals rather than others; hence, as already mentioned, identifying the orientation of their Personal Locus Of Causality (PLOC) is fundamental, prior to carrying out any intervention.

- Valence- Instrumentality- Expectancy (VIE) theory

In this paradigm, motivation refers to three factors

- Valence: what we think we will get out of a given action/behaviour (what’s in it for me?)

- Instrumentality: the belief that if I perform a specific course of action I will succeed (clear path?)

- Expectancy: the belief that I will be definitely able to succeed (self-efficacy)

Implications for the classroom:

(1) make clear to students why a specific outcome is desirable (e.g. getting and A/A* at GCSE speaking exams). Make sure you list as many benefits as possible, especially those that most relevant to their personal preferences, interests and life goals;

(2) provide them with a clear path to get there. This may involve showing them a set of strategies they can use (e.g. autonomously seeking opportunities for practice with native speakers in school) or a clear course of action they can undertake which is within their grasp (e.g. talk to your teacher about how to improve your essay writing; identify with their help the two or three main issues; work out with them some strategies to address those issues; monitor with their help through regular feedback and meetings with them that their are working and if they are not why; etc.). A clear path gives a struggling student a sense of empowerment, especially if they feel that they are being provided with effective tips and support to overcome the obstacles in the way;

(3) support their self-belief that that outcome can be achieved (e.g. by mentioning to them examples of students from previous cohorts of similar ability who did it) and by reminding them of similar/comparable challenges they successfully undertook in the past.

- Goal-related theory

In order to direct ourselves in our personal, educational and professional life we set ourselves goals. These can be:

- Clear (so we know what to do and what not to do)

- Challenging (so we get some stimulation)

- Achievable (so we do not fail)

If we set goals ourselves, rather than having them imposed on us, we are more likely to work harder in order to achieve them. Moreover, Locke and Kristoff (1996) identified specific and challenging goals as those which are more likely to lead to higher achievement.

Implications for the classroom: instead of setting goals for your students in a top-down fashion, involve them actively in the process of learning. Moreover, help the students narrow down the goals set as much as possible and gauge them as accurately as possible to their existing level of competence. E.g.: instead of simply telling a student to check his next essay more accurately next time around and give them a lengthy error checklist, sit down with them and ask them to choose three challenging error categories that they would like to focus on and to aim to attain 80, 90 or even 100% accuracy in those categories in their essay due the following week. Make sure that the knowledge required by the learners to prevent or fix the target errors is learnable and that the students are provided with learning strategies which will assist them in achieving the set goals. I did this in my PhD study with excellent results.

I picked the above theories as they are the ones that I have been using more successfully over 25 years as a classroom teacher and subject leader. It goes without saying that in order to apply them effectively one has to ensure first and foremost that they know and listen to the learners they are dealing with. Cognitive and emotional empathy are a must for the success of any of the above motivational strategies.

These strategies work best in synergy rather than in isolation. In a future post, for instance, I will endeavour to show how attitudinal change may be brought about by using a combination of the above principles to achieve the desired outcomes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.