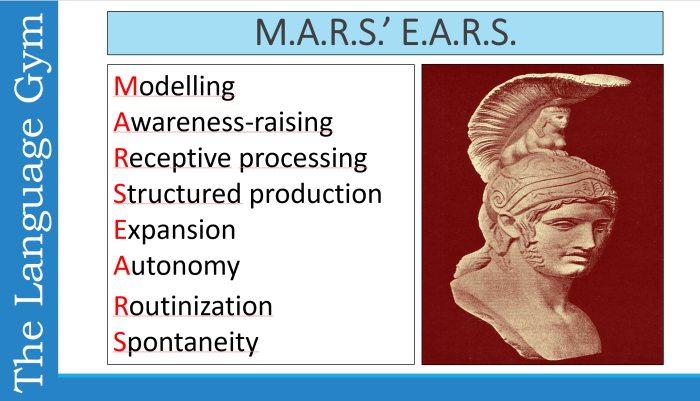

Fig.1 – the MARS EARS framework

0. Introduction

In the first post in this series dedicated to my teaching approach, Extensive Processing Instruction (or E.P.I.), I discussed the M.A.R.S. E.A.R.S. framework in its broad lines.

In the present post I will concern myself with the eight key principles that are crucial for the success of my approach and anyone wanting to adopt E.P.I. ought to heed.

Note that if you haven’t read my previous post, ‘How I teach lexicogrammar (Part 1)‘ I strongly recommend you do before reading on, so as to gain a better understanding of what follows.

1. Chunking

E.P.I. prioritises the teaching of chunks derived from Communicative Functions (see post here) over the teaching of single words and traditional grammar, in the belief that this approach (1) reflects the way the brain is hard-wired to acquire languages; (2) speeds up fluency as it is a faster and more efficient way of producing language; (3) facilitates processing by reducing the cognitive load on working memory; (4) makes language learning more about communication and implicit learning and less about explicit learning and application of rules.

Whilst grammar still places a prominent role in EPI, it serves the expression of communicative functions, hence EPI is about communicative lexicogrammar, construction grammar and usage-based grammar.

For more on the rationale and implementation of chunking, please refer to this previous post of mine

2. Comprehensible Input

Masses of research have evidenced that with average-ability learners any L2 input that is less than 98 % comprehensible (i.e. understandable by the listeners/readers without help) is very unlikely to be conducive to learning. With more gifted learners, 90 % may suffice. Any input below the 80% comprehensibility threshold is likely to cause serious comprehension issues .

It is obvious, then, that if we aim to model L2 language through aural/writen tasks, , we must provide students with comprehensible input which contains language they are largely familiar with. This is very rarely the case with most of published world languages teaching materials, especially coursebooks and, in my experience, with a lot of target language input given by instructors in EFL and WL/MFL classrooms worldwide. The main reason: the belief, rooted in the CLT approach, that students should be given input which is as ‘authentic’ as possible.

However, asking students to perform listening/reading comprehension tasks on aural texts containing a substantive amount of language beyond their comprehensibility threshold encourages the deployment of compensatory strategies (e.g. guessing) rather than the promoting of noticing and modelling of syntax, morphology, lexis and phonology.

Moreover, this practice may be perceived as unfair by the students (e.g. “why am I being asked to listen to/read something I haven’t learnt and don’t understand?”), may engender student anxiety and, should the student fail, undermine their self-efficacy and motivation.

Another dimension of input comprehensibility relates to the speed rate at which aural texts are usually delivered. As noted previously, speed of processing is a function of listening fluency, hence, a beginner student-listener should not be asked to perform a task on texts delivered at native or near-native speed. Yet, this practice is very common in secondary schools in England, with negative consequence for L2-student motivation.

I believe the speed of delivery with beginners ought to be commensurate to their level of listening fluency even at the risk of sounding patently non-native, and should be increased gradually and judiciously as L2 learners’ proficiency grows.

3. Flooded Input

Mothers excel at providing their infant children with masses of input which is simplified, repetitive, highly patterned and rightly pitched to their current level of language proficiency. They ‘flood’ their input with instance after instance of the words or phrases they want their little ones to learn, going back to those words in various ways in their input; in other words, they provide ‘flooded input’.

E.P.I. is big on flooded input. I believe that, at the risk of not sounding authentic, L2 teachers must provide their students with masses of input ‘flooded’ with occurrences of the target linguistic patterns.

This is intuitive: if we want our students to acquire a specific pool of new chunks or to consolidate previously learnt ones, we need to ensure that they occur many times over in our (98% comprehensible) input in order to facilitate their noticing and retention.

Fig. 2 – Nursery rhymes contain lots of flooded input

Flooded input is especially crucial when we deal with items which are less easily noticed by L2 learners (e.g. prepositions, connectives, pronouns, copulas, word-endings) because of their morphology, position in a sentence or simply because of their frequency in L2 input and are consequently acquired quite late by L2 learners. By flooding the aural input with such items thereby increasing the students’ exposure to them, we are more likely to enhance their chances to notice and consequently acquire them.

By the same token, by patterning the input, we ensure that it follows a repetitive and predictable structure which facilitates understanding and retention of the target items. This is very much what happens in the nursery rhymes, songs and stories that children are fed throughout their infancy.

Fig. 3 – A patterned poem flooded with the same target structure

Our emphasis on flooded and patterned input is another major reason why E.P.I. advocates the use of aural/written texts ‘manufactured’ for L2 teaching purposes. One of the benefits of such texts is that they may contain as many instances as we feel fit of items that occur very rarely in the aural input students normally process in the typical L2 classroom. Think about ‘negatives’, for instance: how many ‘authentic’ texts describe events using lots of negative structures?

Narrow reading (NR) and Narrow listening (NL) texts are extreme examples of flooded and highly patterned input. NR and NL consist of clusters of texts (I typically use 4 to 6) which are totally identical except for a few details here and there (see examples in figures 4 and 5 below.

Fig 4 – a set of Spanish narrow reading texts with tasks designed for a year 8 class

Fig 5 – EFL narrow reading texts for French students

Every single interactive read-aloud game described here (e.g. the globally successful ‘Sentence stealer’) aims at providing lots of flooded input.

Fig 6 – The read aloud game ‘Sentence Stealer’ in a lesson on the immediate future in Spanish. Even to non Spanish-speakers the input-flooding is quite obvious.

4. Controlled Input

We believe that in instructed L2 instruction the input we provide our students with needs to be tightly controlled in order to possess all of the attributes discussed above. Note that at the initial stage of a new EPI instructional sequence the input provided to the learners in the Receptive Processing phase (the R in the MARS sequence) does not deviate in any way from the new language patterns and lexical items presented in the modelling phase

L2 learners respond very well to controlled input, because (1) it allows for more recycling of the new items; (2) at the early stages of an instructional sequence, it facilitates processing and reduces cognitive load, as the students do not need to resort to dictionaries or expert help to understand the input; (3) it makes them feel ‘safer, as it decreases the chances of encountering material they are not familiar with.

5. Thorough processing

As noted above, the reading and listening tasks typically found in textbooks and most other published resources usually require students to answer questions on a text that range from ‘who , where, how, etc.’ questions to ‘True or False’ ones. This encourages what we call ‘Partial processing’, as the students do not process the text in its entirety; rather, they skim and/or scan for key words or other intra- or even extra-textual cues which may help them answer the questions. They may, once identified the portions of the text which contain the needed information, read them more thoroughly; however, unless the questions or tasks on the text are numerous and cover every single sentence in the text, several parts of that text will not be processed deeply enough to impact learning.

Moreover, one of the most serious limitations of working memory is its inability to focus on form and meaning at the same time. Hence, if students are asked to perform on texts only task which focus on meaning (e.g. typical ‘who?’, ‘where?’, ‘what ?’ ‘when’ or ‘True or false’ comprehension questions) they will not be able to learn much about the linguistic features in the text, especially the less salient ones.

Yet, for those who, like us, lay a strong emphasis on repeated exposure to the target chunks, lexical patterns and structures in the belief that repeated exposure enhances L2 acquisition, this is an important shortcoming; we want our students to process the text in its entirety; to pay attention to each and every target item so that (1) they become more aware of the way known items behave in a range of phonological, lexical and structural contexts thereby enhancing their acquisition; (2) notice unknown items thereby beginning their acquisition and, (3) if the text contains material that may enhance their knowledge of the world or their well-being, they benefit from it to the fullest extent rather than gathering ‘bitty’ information.

Hence, we advocate that L2 reading and listening tasks should mostly involve thorough processing of the target texts. Typical examples of thorough processing tasks are translations, dictations and error-identification tasks. Some of my favourites:

- Bad translation: the students are given a text in the target language and a translation of the text containing and X number of mistakes. The students are tasked with spotting the mistakes in the translation

- Faulty description: the students are shown a picture and given four narrow reading texts each providing a description of the picture in the target language which contains one more inaccuracies. The students are tasked with spotting the inaccuracies

- Spot the intruder: the students are given a text which contains extraneous words which don’t fit grammatically or in meaning (depending on the focus). The task is to spot the extraneous word

- Sentence puzzles: the students must reconstruct a jumbled-up sentence containing the target sentence pattern and lexis

- Delayed dictation: the teacher utters a sentence that the students will be familiar with, or at least 95-98 % comprehensible input, and tell them to ‘hold it inside their heads’. As they try to keep it in their heads, s/he makes funny noises or utter random words in the target language to distract them for a few seconds. Finally, s/he asks them to write the words on their mini whiteboards and show you.

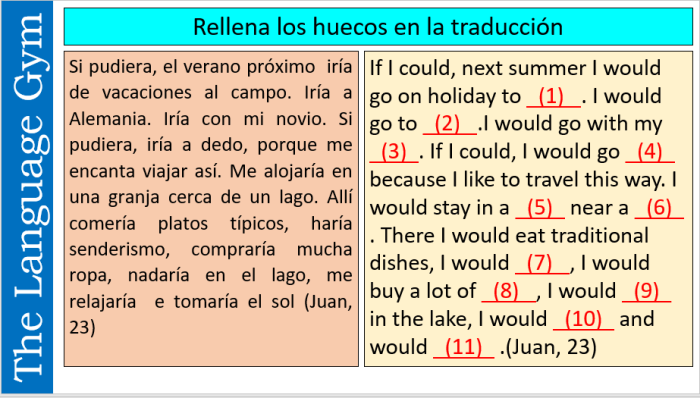

- Gapped parallel texts: the students are given a text in the target language and a translation of that text whose gaps are designed to draw the students’ attention to specific linguistic features.

Fig 7 – A ‘Bad translation’ task for students of Spanish

Fig 8 – Gapped Parallel text for learners of Spanish as a foreign language

6. Pushed Output

As just discussed, I believe that with novice learners the input we provide needs to be tightly controlled in order to possess all of the attributes discussed above. I do also believe that they must be given a wide range of opportunities for transforming every single bit of the input they process receptively into output.

This calls for an approach to the design of oral and written tasks which elicit the production, at the end of a typical instructional sequence (what I call ‘Structured production’), of the very same L2 vocabulary and structures that were modelled and practised through listening and reading at the very beginning of that sequence.

Hence, if, say, you presented and practised through listening and/or reading 20 new vocabulary chunks and 2 new syntactic patterns, you would engage your students in oral and written tasks that force them to produce all of those vocabulary items and patterns many times over – alongside previously learnt linguistic items (interleaving) if you feel these will not cause cognitive overload and interference.

Fig 9 – From controlled input to pushed output

This points to the full integration E.P.I. envisages for listening/reading and to the key role listening holds in priming oracy. It also points to an important difference between Communicative Language Teaching (in its stronger forms) and EPI, i.e. the fact that before engaging in unstructured productive oral and written tasks, L2-learners must sit through an intensive phase of highly structured communicative tasks and drills which recycle the target L2 items to death.

In my opinion, one of the greatest shortcomings of common classroom practice in England is that teachers go way too soon from the Presentation Phase to open-ended tasks and questions which do not enable the teacher to recycle and consolidate at will every single target item, as their students have the freedom to answer as they please -often using the same answer / set of answers in the same way from year 7 to year 11 !

Only highly structured production and targeted retrieval practice can provide sufficient opportunities for the L2 teacher to recycle the target chunks and patterns whilst staying within the limited scope of Feasible Output, i.e. output we know the students are capable of producing.

The effective E.P.I. teacher creates frequent opportunities in the Structured Production phase for Pushed Output which is Controlled (i.e. it is limited to the target patterns and chunks) and Feasible.

Fig 10 – An oral translation game for learners of Spanish as a foreign language involving retrieval practice

Translation drills, mostly interactional games, are the preferred means of elicit pushed output for the reason that they allow the teacher to control the student output as much as possible thereby ensuring that the target items are recycled at will. My favourite translation games and tasks are described here. The rationale for the preference of translation over pictures is that:

- it promotes noticing key differences and similarities between he L1 and the L2, which promotes acquisition;

- it forces the students to use specific chunks/patterns whereas pictures are less narrow in the output they elicit;

As explained in my previous post, after the students have had extensive Pushed Output practice, the teacher will stage tasks involving less structured speaking and writing tasks which involve more creativity and autonomy.

Fig 11 – Oral communictaive drills for learners of French as a foreign language

7. Recycling

I have discussed this point extensively in previous posts. Effective teaching is not just about the effective first lesson on a target item, but also about ensuring that after the intensive recycling that occurs at the initial stages of an instructional sequence that item is extensively recycled over the months and even years to come.

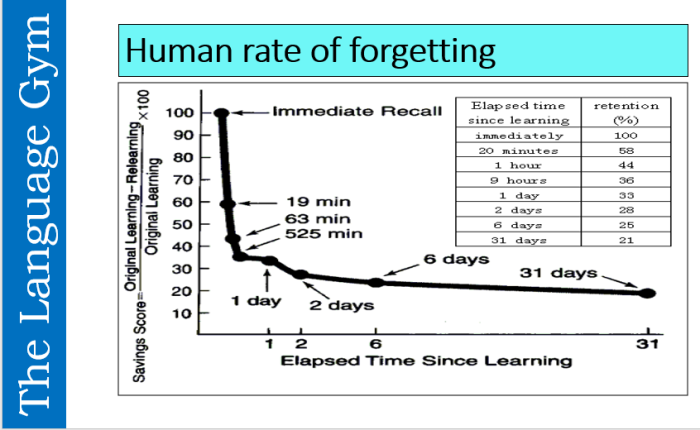

As I have often reiterated in this blog, intensive intra-lesson and inter-lesson recycling are both crucial, as most forgetting (around 56 % ) occurs one hour after processing a to-be-learnt item and after six days, in the absence of reinforcement, the learner is left with very little (30 %).

Fig 12 – Ebbinghaus curve of human forgetting rate

This is why my method is called E.P.I. , where the ‘E’ in the acronym stands for ‘Extensive’ and alludes to the emphasis my methodology lays on carefully planned recycling through Interleaving (explained in detail here), whereby any new set of chunks/patterns is learnt and practised with previously learnt items and recycled with new ones at spaced intervals.

Fig 13- Spaced practice

In the Expansion phase of a typical E.P.I. instructional sequence, for instance, having taught and practised structure ‘Y’ (e.g. Time marker + perfect tense of irregular verbs + prepositional phrase) and being satisfied that the students after a few lessons have routinised the structure in the context of the function ‘Talking about what I did yesterday’, before moving on to a new unit and new material, they will make sure (a) that structure ‘Y’ is practised with structures ‘X’ and ‘W’ learnt in previous units and (b) that it will be practised in all the units to come in some shape or form.

Fig 14 – The Expansion phase in the MARS EARS sequence

The best form of recycling involves of course, spaced practice, whereby material is revisited systematically at intervals that are frequent at the initial stages and become gradually sparser.

Of course, effective recycling require skillful and careful curriculum design and is much harder to implement when one teaches one meaty unit of work every six-seven weeks with two hours of contact time per week.

Hence, my advocacy of a ‘Less is more’ approach, whereby curriculum design in the formative years of L2 learning focuses more on the quality than the quantity of coverage and on the development of automaticity – which brings me to the next point.

8.Automaticity

Automaticity is the ultimate goal of E.P.I., as it is a key prerequisite of fluency. Hence, great emphasis is lain by the E.P.I. teacher on practising speed of retrieval. During the recycling phase, what I called ‘EARS’ in my previous post, tasks such as the ‘4,3,2 technique’, ‘Market place’, ‘Speed dating’, ‘Chain reaction’ and ‘Fast and Furious’ are staged alongside traditional communicative tasks ( e.g. information gap activities) in order to train students in producing language under Real Operating Conditions.

Fig 15 – The 4,3,4 technique

Fig 16 – Chain Reaction. The students, who have three lives, are lined up and are tasked with translating orally on the spot (give them 5-6 seconds) from their L1 into the target language, each chunk as it appears on the slides, losing a life each time they get it wrong. Every time they pass or get something wrong they lose a life. Great as a starter or plenary.

9.Conclusion

Before venturing in subsequent posts in a more detailed account of the various stages in the MARS EARS sequence, from the M (modelling) to the S (spontaneity), I have hereby attempted to outline the key principles of my approach. Any language educator embracing EPI must heed such principles as they are all interdependently crucial to its effectiveness.

Thanks for your posts! Really useful and students love sentence stealers and mind reading. The way you mix higher-order concepts with practical ideas is perfect!

LikeLike

Thank you for the nice testimonial Jorge

LikeLike

Your posts have encouraged me to move to a lexical approach. I have read The Lexical Approach by Michael Lewis (I loved George Woolard way of using literature to teach chunks) and I also have adapted and adopted many of your techniques. At the beginning of the year my 13 year old sudents were a bit perplexed, but now they feel pretty confident with sentence builders and enjoy parallel texts. I’m gathering feedback on my own teaching to make it more rational next year (I’ll try to follow MAR’S EARS). Thanks indeed Gianfranco!

LikeLike

Hi Gianfranco… just a quick question… for you, how long would ideally last the whole MARS’ EARS process? I’m putting it into practice with my 13 year old students and after a month (a total of 12 classes of 55′ each) practicing the comparison in many different ways and having just finished “structured production” I feel that my students are getting tired, although for some of them (the weaker students) comparison is still beyond their grasp… Thanks for your generous help.

LikeLike

Wow ! A whole month is lots. I would spend half that for MARSE. ARS is done throughout the rest of the year, through recycling.

LikeLike

[…] To discuss it, I must give you a quick overview of Dr Gianfranco’s 90 minutes session and warn you; I haven’t included the references to research he made but his work if well referenced and you can easily access a thorough explanation of his approach here and here. […]

LikeLike

[…] sequence described below is largely based on the MARS EARS approach, with a few of my own twists. It is made up of the following […]

LikeLike