0. Introduction

Dictations were taboo for many years in mainstream language education. However, with recent research findings indicating that decoding skills (the ability to match print to sound) are crucial to language acquisition, especially in the realms of listening and reading fluency development, they have become ‘fashionable’ again.

I have always been a passionate advocate of dictation and have been using it for over 30 years as a means to develop decoding and listening skills, but also to foster metalinguistic awareness, vocabulary learning and syntactic knowledge.

In this post, I set out to discuss some of my favourite dictation tasks, reserving to provide a much wider range of techniques in my forthcoming book*.

1.Delayed dictation

Delayed dictation is a great zero-prep activity. Younger learners love it, it’s great fun and helps practise a key language processing skill, ‘holding chunks in working memory’, as well as, of course, decoding and transcription skills. This is how it unfolds:

Step 1 – Utter a sentence that the students are familiar with, or at least 95-98 % comprehensible input, and tell them to ‘hold it inside their heads’ for ten seconds.

Step 2- As they try to hold the sentence in their heads, count up to ten (aloud), make funny noises or utter random words in the target language to distract them .

Step 3 – Finally, ask them to write the words down on their mini whiteboards and show you.

Tip : you can follow this up with ‘Sentence puzzle’ (see below)

The effectiveness of delayed dictation refers to two well-known cognitive mechanisms: the Zeigarnik effect and the ‘Desirable difficulty’ principle.

The ‘Zeigarnik effect’ (Zeigarnick, 1927) posits that a task that has already been started establishes a task-specific tension, which improves retention and cognitive accessibility of the relevant contents. The tension is relieved upon completion of the task. Delayed dictation, by interrupting the task, induces a cognitive tension which may enhance retention.

‘Desirable difficulties’ is a concept develop by R. A. Bjork (1994). The main idea is that introducing difficulties during learning will result in superior long-term retention because the greatest gains in storage strength occur when retrieval strength is low. Delayed dictation involves a desirable difficulty, in that the learner must hold the chunk in working memory as s/he rehearse it prior to writing it down.

Here are two forms of delayed dictation one can deploy to develop students syntactic awareness whilst practicing transcribing skills.

1.1 Delayed dictation with signaled combining

Step 1 – Show the sentence to be combined with the cue in brackets. For instance:

I have a sister (who)

Her name is Marie

Step 2 – Combine the sentences, e.g. I have a sister who is called Marie’ and say it to the class

Step 3 – After 10 seconds, the students write the sentence out on their mini whiteboards.

Tips: this task can be an effective prelude to an explicit sentence-combining task.

1.2 Delayed dictation with open sentence combining

Step 1 – show the sentences to be combined. For instance:

I have a sister

My sister is called Marie

She is friendly, pleasant and helpful

I argue with her from time to time

she is too talkative

Step 2 – combine the sentences according to whichever pattern you intend to model or reinforce, for instance, and utter the resulting sentence, e.g.:

my sister, who is called Marie, is very friendly, pleasant and helpful but from time to time I argue with her because she is too talkative

Step 3 – after 10 seconds, the students are tasked with writing the sentence as the teacher uttered it

Mad dictation

Mad dictation is a dictation in which you alternate slow, moderate, fast and very past pace. It is very successful with students of all ages, but especially younger learners.

Preparation: select a text containing familiar sentence patterns and around 90% comprehensible input.

Step 1 – Tell the students to listen to the text as you read it at near-native speed and to note down key words

Step 2 – Tell them to pair up with another student and to compare the key words they noted down. Tell them they are going to work with that person for the remainder of the task.

Step 3 – Read the text a second time. This time read some bits slowly, some fast and some at moderate pace. The purpose of these changes of speed is to get the students to miss some of the words out.

Step 4 – The students work again with their partner in an attempt to reconstruct the text.

Step 5 – Read the text a final time, still varying the speed of delivery.

Step 5 – The students are given another chance to work with their partner.

Step 6 – They are now given 30 seconds to go around the tables and steal information from other pairs

Tip – some of the students might panic the first time you stage this activity. Hence, it is helpful to let them know how the activity will unfold.

3. Sentence puzzles with metalinguistic categories

Sentence puzzles are a great way to sensitize students to syntactic order through the aural medium. A fantastic (recapping) lesson starter or plenary task that students love. When you add the metalinguistic categories element, you also enhance their language awareness and contribute to the explicit development of their parsing skills.

Step 1 – Write on the board the short-hand / symbols of a sentence pattern you have modelled and your students are familiar with. For instance, :

Time marker + Subject + Verb + Adverb of place

Step 2 – Ask the students to copy out the above in their books / or mini whiteboard

Step 3 – Utter a jumbled-up version of a sentence which follows that pattern. Ensure the students are very familiar with every word in the sentence

Step 4 – The students now unjumble the sentences they hear placing each element under the appropriate heading. For example :

Time marker Subject Verb Adverbial of place

Hier Je suis allé au cinéma

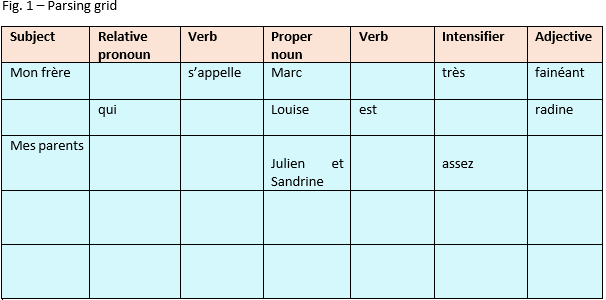

- Partial dictations with parsing grids

Partial dictations can be used to focus students explicitly on phonology, morphology and syntax by omitting from the gapped text the students must complete a key constituent of the target structure. In this sense, they can effectively promote noticing.

For instance, as far as phonology are concerned, you could gap the parts of word which refer to the target sounds and students will have to complete the words as they listen.

In the realm of morphology, instead, imagine teaching the perfect tense of French verbs ; you could gap all the auxiliaries or all the past participles. Another example pertains to word ending in highly inflected languages, which could be gapped to draw the students’ attention to the gender and number of nouns/adjectives or to verb tenses and/or conjugations.

Parsing grids (see example in Fig. 1 below) can be used in combination with partial dictations, thereby focusing the students more explicitly on syntax.

5. Spot the missing word

In this task, words are omitted from the text. In this sense, it could be considered a partial dictation, the notable difference being that the students are not alerted to the presence of a gap by a blank space.

To add a metalinguistic focus, the words removed could refer to item the students usually tend to omit by mistake (e.g. the auxiliary in the formation of the perfect tense in French or Italian).

Step 1 – Remove words (containing the target sounds if your focus in phonological) from a text.

Step 2 – Read out the text

Step 3 – The students are required to write down the missing words in the correct place

6. Write it as you hear it

This task is not a dictation in the traditional sense of the word, but it is very effective in raising student awareness of GPC (grapheme-phoneme correspondence) through the transcription of oral input, by contrasting the way words sound with their spelling. For this reason, this task is most useful with less transparent languages such as English and French. This is how it unfolds:

Step 1 – Display a few sentences on the board and give the students a copy of those sentences on a sheet

Step 2 – Read them out at moderate pace enunciating them as clearly as possible

Step 3 – Ask the students, as they listen, to write, under the correct version they have their own phonetic transcription of what they heard.

Step 4 – Ask them to pair up with two other students and to come up with a phonetic transcription they all agree with

7. Syllabling

Syllable processing may contribute more to the all-important decoding phase of listening comprehension than phoneme processing (Field, 2015).

A growing body of research suggests that we process aural input by dividing it in syllables not in phonemes, as it is commonly believed.

Syllable-level information appears to contribute more than is sometimes realised to effective processing for the following reasons (Field, 2015):

(1) many words are monosyllabic;

(2) single stressed syllable provide cues to the identity of longer words;

(3) to the function of words (content versus function words) and

(4) to where the boundaries of words fall.

(5) The rhythm of a language is shaped by what happens at syllable level.

Yet, most listening instruction concerns itself with phonemes. As John Field points out, in focusing on syllables, EFL teachers need to concern themselves with at least three factors which shape a language’s rhythm.

(1) the structure of a syllable (i.e. the number of consonants that a language permits within a syllable). Most languages have a CV (consonant – vowel) and CVC. Spanish and Italian rely heavily on open CV syllable. English allows very complex structures (e.g. CCCVCCCC, e.g. in the word strengths).

(2) the frequency of weak syllables (like those in English containing schwa ).

(3) the ratio between the time taken by weak and by strong syllables.

An unfamiliar rhythm can interfere significantly with a listener’s ability to recognize known words in connected speech.

There is a fixed number of syllables, around 500, in every languages. This is one of a range of activities I have used over the years to focus my student onto the most frequent syllables in the target language.

Step 1 – Dictate syllable by syllable. Students transcribe

Step 2 – Dictate syllable by syllable again. Students check and make changes if they feel fit

Step 4 – Students pair up with another student and compare transcriptions

8. Read, look up and say it

This task combines a technique originally devised by Jones (1960), ‘Read and look up’, with dictation. It is a form of dictation with a double whammy, in that both partners are actually being challenged.

Step 1 – Partner 1, who dictates, must read silently a set of sentences one by one.

Step 2 – he must then look up and repeat each sentence to Partner 2 without looking at the text as s/he speaks. Every time s/he manages to recall the full sentence s/he scores a point per word s/he remembers correctly.

Step 3 – Partner 2, on the other hand, will get a point for each word s/he transcribes correctly

9.Collocational grids

9.1 Modelling dictation

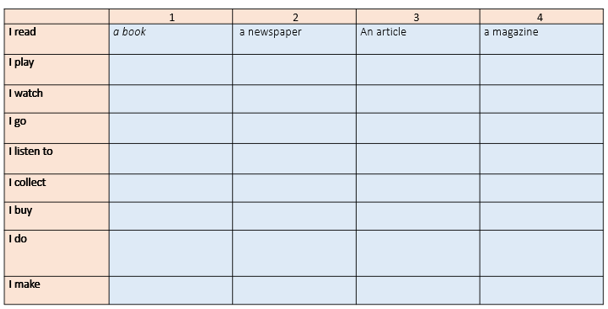

Collocational grids (see example in Fig 2) can be used to model collocations, as in the activity below:

Step 1 – Give a students a grid like the one in figure 1 below, designed to practise verb collocations, in which the first collocation partner is provided (e.g. I read , I play, I watch, I listen to)

Step 2 – Utter sentences which contain both the first and the second collocation partner too (e.g. I read a book, I play tennis, I watch a film, I listen to a song) whilst the students note them down in the appropriate row of the grid (e.g. book, poem, article, novel, will be written on the same row as ‘read’)

Fig 2. – A collocational grid

9.2 Retrieval practice

Collocational grids can also be used for retrieval practice. For instance, going back to the example in the picture, you could utter the noun phrases ‘a book’ , ‘a gift’, ‘stamps’, ‘music’,etc. in random order, and the students will have to write them on the correct row.

10.Concluding remarks

There is much more to dictation than meets the eyes. As the examples above clearly show, they can impact L2 development on different levels, from spelling to decoding skills, vocabulary and syntax. What is key, as I always reiterate, is to ensure the input is 98 % comprehensible, and flooded with many occurrences of the target patterns. The point in the instructional sequence they occur at is evidently also crucial.

Very interesting ideas that have a great practical application!

LikeLike

thank you

LikeLike