Five common pitfalls of L2-grammar instruction

Most teachers nowadays agree that grammar instruction plays an important role in effective foreign language instruction. There are, however, a number of important factors that one has to take into consideration in the planning, delivery and evaluation of the effects of grammar instruction which are often overlooked, thereby undermining its efficacy. Such factors, which relate to both our epistemological assumptions about the nature of language learning and to neuroscience in general, can seriously undermine the effectiveness of our teaching as well as be important causes of daily teacher frustration. Here are five of the most common pitfalls of grammar instruction that I have witnessed in nearly three decades of MFL teaching.

Pitfall 1: too much focus on declarative knowledge

A few years back I inherited from a colleague the ‘dream year 9 class’, a class that is, which included la crème de la crème of the students in my school. I was excited as I had taught some of these students before and I knew how keen and bright they were. On the first day of meeting them, one boy, Shaneel, told me ‘Sir, we have already learnt ALL of the (French) tenses!’. I was a bit skeptical but gave them the chance to show off their prodigious knowledge of the five tenses in question by asking them to translate sentences from English to French on mini-boards. The result was disastrous. ‘Wait, Sir’ this is not how we learnt it!’ protested Shaneel, we learnt them like this, and he recited to me – fairly accurately – scores of verb conjugation tables much in the same way I had learnt Latin at Grammar School.

In other words, Shaneel had declarative knowledge of the Present, Perfect tense, etc. and all of the other grammar structures he had been taught, but was not able to transfer that knowledge to real life use (especially in the oral medium) across various semantic contexts. The reason? He had not been given enough opportunities in lessons, to acquire executive control over the target grammar structures across the following dimension of learning: (a) skills/modalities (L,R,S and W); (b) semantic areas; (c) communicative pressure.

The dichotomy Declarative/Procedural refers to the distinction between having intellectual knowledge about a target structure as opposed to the ability to apply the same knowledge subconsciously bypassing working memory’s attentional systems. According to many models of second language acquisition these two types of knowledge are completely separated, and several of them (see Stephen Krashen’s, for instance) posit that declarative knowledge can NEVER be converted into procedural knowledge. In other words, knowing a grammar rule, does not equate in the least with being able to use it spontaneously and automatically in unmonitored communication.

The obvious Implication for grammar instruction is that to assume that students have acquired a given structure based on their recall of grammar conjugation (by rote) or their effective executions of gap-fill activities is completely erroneous. The acquisition of a grammar structure takes a very long time and cuts across many dimension of morphology, syntax and meaning; hence, teachers should not feel as frustrated as in my experience often do at seeing structures that have been taught over and over again being deployed erroneously by their students in their oral or written output. It may simply mean that more extensive practice is required – not necessarily more intellectual knowledge.

In conclusion, online verb conjugation trainers (e.g. www.language-gym.com), Gap-fill exercises and all other activities aiming at enhancing morphological manipulation skills are useful but must be used in conjunction with translation and scores of real time communicative (oral and written) tasks.

Moreover, if we accept the notion advanced by most psycholinguists that intellectual knowledge about grammar (which is the one student obtain through correction and formative assessment) does not really impact acquisition, we will understand why error correction often has very little impact on our students’ mastery of the most complex structures (see the first article on this blog, below)

Pitfall 2: Developmental ‘unreadiness’

The Natural Order of Morpheme Acquisition Hypothesis is a theory based on a fairly large body of evidence which seems to indicate that humans acquire grammar in an order predetermined by nature. Although I do not espouse this theory of Language Acquisition, researchers working in this paradigm have gathered useful evidence indicating that there are some developmental constraints which limit our brain’s ability to learn the target language grammar structures. Such constraints are due to the challenges posed by such structures to the developing linguistic skills of the L1/L2 learner at given moments in time. To use an analogy: before teaching someone how to park, you would teach them how to start the engine, reverse, how to engage the clutch,etc. By the same token if grammar structure X requires the knowledge of grammar structure Y for its effective execution, one would have to be able to perform Y effectively before being able to learn X. The list below shows, for instance, the order of first language acquisition of English Morphemes in R. Brown (1973):

1 Present progressive (-ing)

2/3 in, on

4 Plural (-s)

5 Past irregular

6 Possessive (-’s)

7 Uncontractible copula (is, am, are)

8 Articles (a, the)

9 Past regular (-ed) 10 Third person singular (-s)

11 Third person irregular

12 Uncontractible auxiliary (is, am, are)

13 Contractible copula

14 Contractible auxiliary

Although I do not believe that the above order is necessarily correct and all of the evidence produced in its support valid, the Natural Order Hypothesis points to the importance of developmental readiness and has one important implication for language learning: that without getting bogged down with which morpheme comes first or second or third, we need to sequence the order in which we teach grammatical structures judiciously, based more on our cognitive empathy with the students and our experience of teaching equivalent groups of learners in the past rather than on the textbook or schemes of work provided by the Ministry of Education of Local authorities. Our presumptions of what constitutes an easy or challenging grammar structure for our students may not coincide with our student’s developmental readiness to acquire it. Grammar structures must be taught and corrected only when the students are developmentally ready to acquire them, in order for grammar instruction to be effective.

Pitfall 3: The rate of human forgetting / Poor recycling

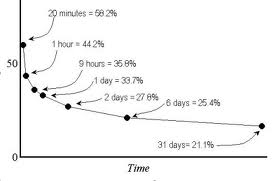

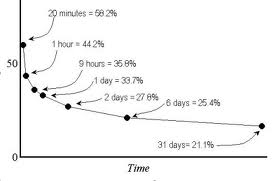

Picture 1, below, shows the way us humans ‘forget’ the information we have been initially exposed to. As many studies have clearly proven, after only two days 70% of what we have been taught/processes on day 1, is lost. After seven days without any memory rehearsal, about 80 % of it is forgotten. Unless, through constant recycling, the modelling of effective revision strategies and continuous formative and summative mini-assessments teachers keep the memory traces alive, the human rate of forgetting is such that even the best grammar lesson will be forgotten.

Picture 1- Rate of human forgetting

Unfortunately, in my career I have rarely seen grammatical structures (or even vocabulary) being recycled constantly and in a principled way – fear of interference being often the obstacle, e.g. : if I revise the present tense now that I have just introduced the Perfect Tense, my students will be confused. Constant recycling, however, is absolutely imperative.

Poor recycling often also explains the inefficacy of a specific type of grammar instruction, correction, and why spending hours recording formative feedback on an App like Explaining everything may simply not impact learners much. The intellectual knowledge – which may not become procedural for the reason mentioned above – produced by these means will be mostly lost unless teachers provide constant recycling of that feedback over the five six weeks following the provision of that feedback (honestly: how many teachers actually do that?).

Pitfall 4: Low cognitive empathy

Cognitive empathy is a term I coined a couple of days ago during a discussion with a colleague. My point being that to be an effective teacher you must not simply be emotionally empathetic but also in sync with the learners’ thought processes and general cognitive development. AFL strategies do help a lot in terms of giving us an insight into how well our students our doing in learning what we are teaching them. However, they do not give us sufficient insight into the cognitive barriers to acquiring a specific target grammar structures. For instance, in the planning phase of teaching the Perfect tense in French one should think about all the possible obstacles posed by the following to the students cognitively (not just in terms of intellectual learning, but also in terms of acquisition as defined above):

- The learners’ grammar background (how well do they master the present tense of AVOIR and ETRE?; do they know how to pronounce ‘e’ with an acute accent?; etc.)

- The native language (does their native language have an equivalent of this tense? Will it cause interference?)

- The various steps needed to be able to master the perfect tense (deciding whether it is the correct context for Perfect Tense use, correctly choosing the required form of the correct auxiliary; deciding if the verb is regular or irregular, select the correct regular or irregular form of the past participle; pronouncing it correctly)

- The time available for it to be learnt DECLARATIVELY;

- The time available for it to be learnt PROCEDURALLY (i.e. automatized)

Another useful strategy to deploy whilst planning our lessons is to cast our mind back to the days when we learnt the same grammar structures as L2 learners of French: what did we find hard? What strategies did we come up with to facilitate our own learning? How long did it take us to learn that tense? Our (L1 English) students will have more or less the same issues, after all. This should enhance our cognitive empathy.

Finally, there are useful techniques that I have used several times to gain a better insight into our students’ learners cognitive processes. One of them is think-aloud protocols a very powerful (if time consuming process) tool to get into our students’ minds: students perform a task (e.g. writing an essay) whilst verbalizing every single thought that goes through their heads. Getting them to write an account of a past holiday after a cycle of lessons on the Perfect tense in front of you while thinking aloud will provide you with a clearer understanding of how well they master the Perfect Tense in real operating conditions and of their problems with that tense (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Think_aloud_protocol )

I have observed poor cognitive empathy in many lessons over the years. Students resent it as much as they resent lack of emotional empathy or humour. High levels of cognitive empathy are, in my opinion, the marker of an excellent practitioner.

Pitfall 5: Lack of a common metalanguage

If teacher and students do not share a common metalanguage, grammar instruction is less effective. Several studies have shown that students who do have a solid repertoire of metawords (adjectives, mood, tense, ect.) learn grammar more effectively both in and outside the classroom (independently). They also learn more effectively from corrective feedback. One anecdote I will never forget was when I inherited a class from my former colleague Gill Bruce and since she had taught her students the difference between an adverb and an adjective, I could –for the first time ever – very quickly get my students to understand the difference between ‘mal’ et ‘mauvais’ in French by simply saying: one is an adverb and the other one is an adjective.

The implications for teachers is that we need to use metalanguage from the very start and make constant reference to it (in our marking, too).

In conclusion, in planning and delivering our grammar lessons one has to be very mindful of all of the above factors. We are often reminded by scholars and educators of the importance to empathize with our students emotionally since, as my colleague Dr Michael Browning rightly said to me once: “if they like you a lot they will learn better anyway, regardless of which technique or technology you use”. However, empathizing cognitively in terms of truly attempting to (a) sync our teaching to their specific individual linguistic needs and (b) to the way their brain works when acquiring a foreign language (as posited by neuroscience) is imperative in order for us to pace our teaching effectively and to intervene effectively through adequate remedial instruction.

You must be logged in to post a comment.